Asset Allocation Weekly (January 25, 2019)

by Asset Allocation Committee

One of the important unknown factors for 2019 is whether slowing global growth will have a negative impact on the U.S. economy. Or, put another way, can the world lead the U.S. into recession? For the most part, history suggests the answer is no—the U.S. can bring down the world but the world can’t bring down the U.S.

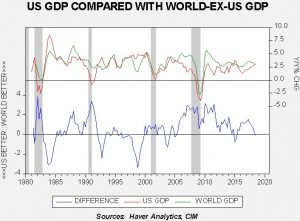

The upper two lines show the yearly change in U.S. GDP and World ex-U.S. GDP. The lower line shows the difference. World and U.S. GDP are positively correlated at the 70% level, suggesting they are sensitive to each other. Since the U.S. provides the reserve currency it would make sense that a stronger U.S. economy would also support imports from abroad which would foster foreign economic growth. However, the U.S. doesn’t export as much relative to its size as other nations do, so it follows that stronger U.S. growth would support higher world growth but better growth in the rest of the world wouldn’t necessarily lead to better American growth.

A couple of examples show this pattern. In the late 1990s, world GDP growth fell sharply while the U.S. was unaffected. The Asian Economic Crisis and the Russian debt default did not derail the U.S. economy. In 2005, the U.S. economy began to slump due to the deflating housing bubble. World growth did hold up into 2008 but eventually succumbed to follow the U.S. into recession.

At the same time, this analysis doesn’t mean policymakers should ignore the world. In theory, the Federal Reserve’s mandate is full employment and low inflation. Since these goals can be mutually exclusive at times, the Fed has tended to leave both specifically undefined. That has changed; the Fed now has a semiformal[1] 2% core PCE goal, which means the full employment goal is even more amorphous. When asked about the world, Fed officials are usually circumspect but do say they will address the issue if overseas events affect the U.S. economy. The above research suggests this comment is something of a “fudge”; the world rarely affects the U.S. directly. But, there are times when the Fed does appear to move policy in light of world events.

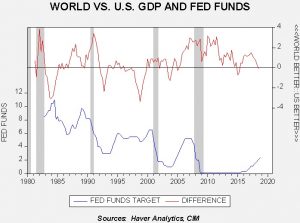

A couple of events are notable, where the Fed appeared to have adjusted policy due to global events. In the early 1980s, the Fed was still managing interest rates by focusing on the money supply. However, the high level of interest rates led Mexico to default and caused cascading debt crises throughout the region. The Volcker and Greenspan Feds reacted by cutting interest rates from 11% to 6% and the spread between U.S. and global growth narrowed. The Greenspan Fed eventually cut rates during the Asian Economic Crisis and the Russian debt default in the late 1990s, although the Long-Term Capital Management debacle contributed to that move. We also note that the Fed continued to reduce rates into 2004 even though the recession had ended; while weak global growth may have contributed, as we discussed two weeks ago, high equity market volatility probably contributed as well.

If the FOMC is looking for an excuse to ease policy, it could certainly use concerns about global growth affecting the U.S. economy as a reason. Although we doubt that the weak global economy will bring down American growth, concerns about it could allow the Fed to lower rates and maintain credibility. So far, we have not seen any indication that this factor is affecting policy, but it would not be a stretch to see the reason pop up in comments and statements from the U.S. central bank to at least justify a sustained pause in rate hikes.

[1] It’s semiformal because Congress hasn’t given the Fed an exact mandate.