Asset Allocation Weekly (September 25, 2020)

by Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

For more than a decade, U.S. investors who diversified their risk assets to include foreign equities have been sorely disappointed in the results. Since September 2010, for example, the S&P 500 Index of large cap U.S. stocks has provided an average annual total return of approximately 13.9%, but the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. Index of foreign stocks has provided a total return averaging just 4.6%. At those rates of return, an all-U.S. stock portfolio would have doubled in value every 5.2 years or so, whereas an all-foreign stock portfolio would have taken about 15.7 years to double. Even a broad index of U.S. corporate bonds would have beaten the broad foreign stock market over the last decade, with only about one-third as much volatility! It should be no wonder that many investors have chosen to exclude foreign stocks from their portfolios.

But if you understand the key drivers behind the U.S. outperformance and foreign underperformance in recent years, it can clarify your thinking about the proper asset allocation strategy for the coming years. As we’ve argued repeatedly, much of the difference in U.S. versus foreign stock returns can be traced to the foreign exchange value of the U.S. dollar. When the greenback is strong and appreciating, the broad U.S. stock indexes tend to show better returns than the foreign indexes. Indeed, the dollar was generally rising from mid-2011 to mid-2020, explaining much of the U.S. outperformance over the last decade. In contrast, when the greenback is weak and falling, foreign indexes tend to outperform. That’s important because it appears the dollar has recently rolled over and begun what could well be an extended slide. If so, the coming period is likely to strongly favor foreign stocks.

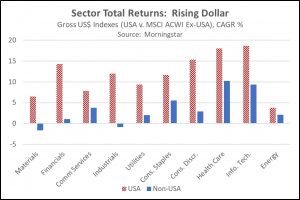

Of course, some of the recent outperformance of U.S. stocks simply reflects the preponderance of large cap Technology and Health Care names in the U.S. indexes. Those stocks have been particularly in vogue and have shown extraordinary growth in recent years. Nevertheless, taking a deeper dive into the relative performance of U.S. and foreign stock market sectors shows that the strength of the dollar is the predominant factor. If foreign stocks outperform U.S. stocks across a wide variety of sectors during a weak-dollar period, it should help confirm that the relationship is the most useful guidepost, and that is indeed what the data shows. This can be seen by examining the first chart below, which shows the outperformance of U.S. stocks (represented by striped red columns) versus foreign stocks (solid blue columns) over the last two strong-dollar periods from May 1995 to February 2002 and from May 2011 to July 2020. During these periods, U.S. total returns roundly beat foreign stock returns in all sectors for which comparable data was available (the data exclude real estate).

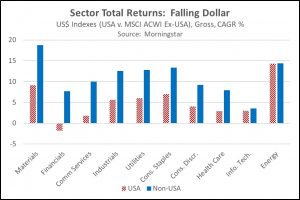

In contrast, the chart below shows how dramatically foreign stocks turned the tables during the period of dollar weakness from February 2002 to May 2011. In this period, foreign stocks handily beat U.S. returns in almost all sectors. The sectors are shown, from left to right, in the order by which the foreign returns beat the U.S. returns. The graph clearly demonstrates how dramatically foreign Materials, Financials, Communication Services, and Industrials stocks outperformed their U.S. counterparts as the dollar declined. Given the significantly greater exposure to Materials, Financials, and Industrials in the foreign indexes, those sectors account for most of the overall foreign outperformance during the weak-dollar period. In the high-growth Information Technology and Health Care sectors, foreign stocks also outperformed their U.S. counterparts as the dollar declined, but the relative underrepresentation of those stocks abroad kept the foreign outperformance smaller than it otherwise would have been.

Although the data set used in this study only began in 1995, covering just two rising-dollar periods and one falling-dollar period, the relationships described above make logical sense. For example, a low or falling dollar tends to support commodity prices, so foreign Materials firms should see improved finances when the greenback is sliding. Our analysis also indicates that foreign emerging market stocks have an even more pronounced advantage in a falling-dollar phase. In sum, the analysis indicates that if the dollar is indeed falling into a prolonged downtrend like we think, the new investment environment is likely to favor a wide swath of foreign equities in the coming years.