Weekly Geopolitical Report – The Geopolitics of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC): Part I (March 15, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

There has been a surge in interest in digital currencies among the world’s central banks. The triggering event was probably Facebook’s (FB, USD, 264.28) unveiling of the LIBRA project in June 2019. Digital currencies of various stripes have been around for some time; bitcoin (BTR, USD, 49,989.80), introduced in 2009, is one of the oldest. For the most part, central banks have not felt threatened by bitcoin because the cryptocurrency fails to meet the standards of a currency (which we will discuss in greater detail below). First, it is difficult to use in transactions. Because bitcoin does not have a central repository for executing transactions, it relies on “miners” who receive bitcoins for verifying the accounts in a transaction. Miners earn the right to execute the verification by cracking puzzles that use large and growing amounts of electricity. In fact, the energy consumption has reached the point where China has halted mining in Inner Mongolia, an area of cheap electricity. In addition, the price volatility of bitcoin makes it difficult to use as a store of value. If bitcoin were your only currency, you would be facing rapid changes in prices and, for the most part, persistent deflation. Finally, it may not be safe; the blockchain is vulnerable to being corrupted and its impermanent nature could lead to governments ending its existence.

However, when Facebook entered the cryptocurrency realm, central banks took notice. Not only could the tech firm have the resources to manage a payment system, it has a widely adopted platform in place. Therefore, interest began to grow among central banks who wanted to determine if they should begin offering a digital form of currency.

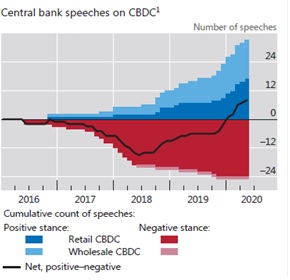

This chart shows central bank speeches on the topic of CBDC. They started in earnest after 2016; initially, the tone was negative, but it has steadily turned more positive beginning in 2018 and went net positive early last year.

Another factor that has fostered the interest in CBDC is the pandemic. Social distancing and the goal of reducing virus transmission encouraged cashless payments which were not always available, especially to the less affluent. In addition, the distribution of fiscal aid was hampered by the lack of financial services among the same groups. It is thought that a digital currency may have helped resolve these two issues.

So, why is CBDC a geopolitical topic? It is estimated that around 80% of the world’s central banks are considering and investigating the introduction of CBDC. As we will detail in this report, central banks will have choices in how they structure their CBDC. But these digital currencies won’t exist in a vacuum; firms and individual countries will likely use these currencies as well, so there will be an international impact to their issuances.

Part I of this series is an examination of what money is. Part II will begin with a discussion of the current state of money and show how CBDC can act as money in multiple ways. We will also examine how the digital currency’s structure could have significant effects on financial systems, fiscal policy, privacy, and data collection. Part III will analyze the geopolitics of the introduction of CBDC, and Part IV will discuss potential market ramifications.