Weekly Energy Update (April 29, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

After the recent rally in prices, the market is consolidating recent gains and establishing a larger trading range between $68 to $58 per barrel.

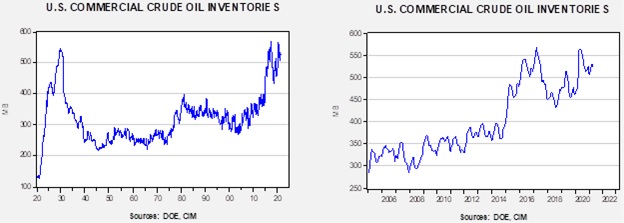

Crude oil inventories rose 0.1 mb compared to the 1.0 mb draw expected. The SPR fell 1.4 mb, meaning without the addition from the reserve, commercial inventories would have declined 1.3 mb.

In the details, U.S. crude oil production declined 0.1 mbpd to 10.9 mbpd. Exports were also unchanged while imports rose 1.4 mbpd. Refining activity rose 0.4 mbpd.

(Sources: DOE, CIM)

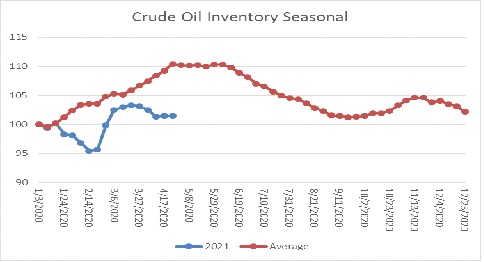

This chart shows the seasonal pattern for crude oil inventories. We are now at the peak of the winter/early spring build season. Until the Texas freeze, we were seeing a counterseasonal decline. This week, stockpiles were mostly steady. We are currently at a seasonal deficit of 40.6 mb.

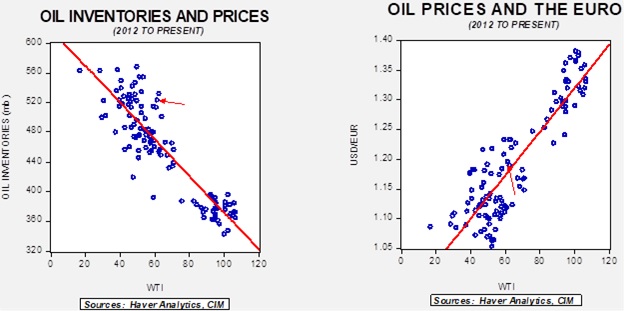

Based on our oil inventory/price model, fair value is $43.72; using the euro/price model, fair value is $65.91. The combined model, a broader analysis of the oil price, generates a fair value of $53.66.

(Sources: DOE, CIM)

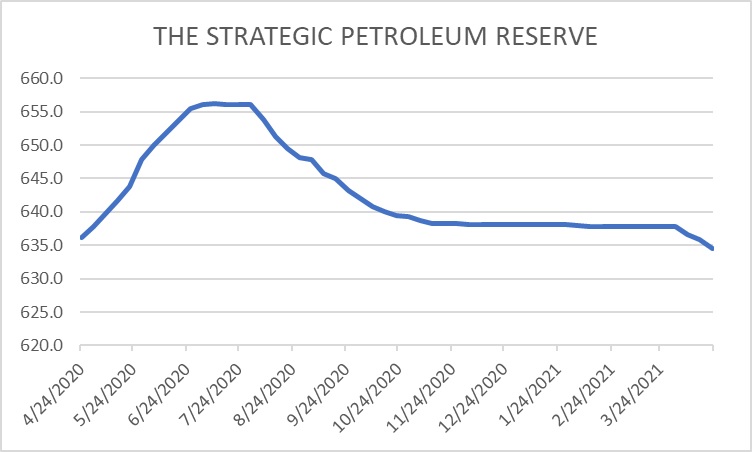

One of the factors that led to last year’s price collapse was the fear the market would run out of storage capacity. To prevent that outcome, the U.S. purchased around 20 mb of crude oil from late April into early July. Since peaking at 656.1 mb, the government reduced the SPR to 637.8 mb in February. It held stocks at that level until three weeks ago when the government began to reduce the SPR again. We note that current SPR levels are below the level where the pandemic affected the market. In fact, this week’s reading is the lowest SPR level since 2003.

Congress has mandated a sale of 10 mb this year; so far, they have sold 3.6 mb of that mandate. We have been a bit surprised at the speed of the sale. However, it does appear that the plan is to move quickly to meet the mandate. Longer-term, the SPR poses a problem. If the U.S. holds on to the oil, and the world moves away from it, the reserve could become a stranded asset, similar to an oil company’s oil reserves when oil isn’t used. This issue would suggest the government should sell the reserve down before it loses its value. At the same time, the economy still consumes a significant amount of oil, and having the reserve in place protects the economy from a supply shock. It is possible that environmentalists would protest the sale of the oil to prevent its consumption from lifting carbon emissions. Another use could be to contain oil prices if the lack of investment by oil companies curtails supply and lifts the price. The SPR will bear watching in the coming months; although another 7.4 mb will be sold, what the administration does after that could be important.

Market news:

- The shipping industry is being forced to move from high sulfur bunker fuels to less polluting ones. Although lower sulfur diesel is the likely alternative, hydrogen is also a potential replacement.

- Exxon (XOM, USD, 56.96) is facing an activist revolt. The company’s management has been resolute in maintaining its fossil fuel production in the face of climate change regulation. A group of stock activists is pushing the company to reconsider, offering a slate of new directors.

- Although U.S. production has rebounded from the pandemic lows, it remains well below the previous peak. Returning to that peak will likely require shale firms to attract funding, which remains a serious challenge.

Geopolitical news:

- The KSA is planning to sell off additional parts of Saudi Aramco (2222, SAR, 35.80). Ascertaining the motive for steadily selling off what used to be a strategic asset by the kingdom is not exactly clear. It could be that CP Salman simply needs the money. We suspect the KSA realizes the age of oil is coming to a close and, thus, monetizing the country’s biggest asset while it still has value makes sense.

- CP Salman indicated that he wants to improve ties with Iran. We have been watching the two nations take tentative steps to reduce tensions. On the one hand, the KSA and Iran have aspirations to be the dominant regional power. On the other, as the U.S. begins to back away from the region, these nations will need to figure out how to cope with the resulting power vacuum and may conclude that they will need some degree of cooperation to prevent chaos.

- Total (TOT, USD, 44.92) declared force majeure on a $20 billion LNG project in Mozambique. The project and the country have been under attack from Islamic insurgents. This project is Africa’s largest private investment, and the declaration is a clear setback for the company and the region.

- A leaked tape in Iran confirms what we have suspected for some time—the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRCG) is the real power in the country. We continue to watch to see if, when Ayatollah Khomeini dies, if the IRGC continues the fiction of the rule by clerics or simply takes power.

- The U.S. is signaling to Iran that it will consider removing some sanctions to facilitate a return to the Obama-era nuclear deal. It is unclear if this will be enough to entice Iran to reduce uranium enrichment.

- At the same time, the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard and elements of the IRGC have been engaging in skirmishes in the Persian Gulf. It is unclear why the hostilities have emerged. It is possible Iran is probing the Biden administration to gauge a response. Tehran could be using the tensions to improve its bargaining position. Nevertheless, anything there is a confrontation, the risk of an escalation is possible.

Alternative energy/policy news:

- Economists generally accept the notion that controlling carbon emissions will be best served by an appropriate carbon price. Once a price on carbon emissions is put into place, the powerful market mechanism will be triggered, which will lead to society better balancing the need for energy against the adjusted environmental cost. The market mechanism is efficient in securing outcomes, but its efficiency can be brutal. One key problem is that the market pays little attention to who bears the burden of the cost, and it is often applied to those least able to handle it. We note that President Biden’s climate policy says nothing about carbon pricing. We doubt this isn’t due to economists around him not suggesting it should be part of it; instead, this is likely a political calculation. So, despite the industry calling for carbon pricing, the president’s plan relies on less efficient mandates.

- Although improving the power grid in the U.S. is peripherally associated with addressing climate change, the administration has allocated $8.0 billion in its climate package to this goal. The U.S. electrical grid is substandard. The Texas experience last winter made that evident. There has been underinvestment in the grid for years. If wind power is going to expand, a better grid will be necessary to bring that power from the rural areas where the wind blows to the urban areas where the power needs are the greatest.

- The administration is also pushing for an expansion of offshore wind projects. These have a certain allure; if they are over the horizon, no one on land sees them. Yet, these projects face state regulations and other hurdles. The administration has been arguing that green projects will spawn high-paying jobs, but that remains to be seen. In fact, if high labor costs are part of the process, it may reduce the expansion of green energy.

- The U.S. is considering a European plan to mandate climate risk exposures. Although disclosures can be a powerful tool, it is also notable that annual reports are full of footnotes that often investors overlook. It is quite possible that the goal of disclosures is a form of “greenwashing,” which will do little more than admit that there is a climate impact to a company’s activity but little more.

- A U.N. study is calling for better management of methane leaks from oil and gas projects. If the industry cannot control such leaks more effectively, it runs the risk of curtailing natural gas production, which, although not completely green, has much lower carbon emissions than other fossil fuels. This is especially true in China. Substituting natural gas for coal would have a marked effect on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It will need to get that gas from abroad, and if regulation due to methane reduces that supply, we may end up with the continued use of coal.

- One problem with reducing the use of fossil fuels is that we are moving from dense to less-dense energy sources. Although efficiency gains in consumption may offset some of this problem, the fact remains that much of the industrial revolution was built on getting more energy out of smaller sources. One way to overcome this problem would be to apply the world’s most dense energy source, uranium. We note that the industry has been enjoying a bit of a renaissance as environmentalists rediscover the benefits of nuclear power.