Daily Comment (April 7, 2016)

by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

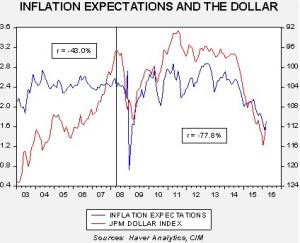

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] Yesterday’s FOMC minutes generally confirmed what we have been hearing from committee members over the past few weeks, namely, that international concerns are worrying members and keeping policy steady. Of the 17 members on the committee, eight viewed the risks to be shifting toward slower growth, while six saw the risks as balanced between slower growth and inflation. Eleven members expected inflation to trend lower. These numbers suggest a dovish bias, so it seems unlikely that the Fed will move to raise rates this month. This chart actually captures two of the risks mentioned by Fed members recently, international developments and the weakness in market inflation projections.

This chart shows the five-year forward inflation expectations from the TIPS spread and the JPM dollar index (on an inverted scale). Since early 2008, the correlation between these two series is 77.8%; essentially, the dollar appears to be driving inflation expectations. Although we would never expect the Fed to openly target the dollar for policy purposes, in fact, weakening the dollar is probably the best remaining tool in the Fed’s policy toolbox. Unfortunately for the FOMC, there are two problems with this policy. First, the exchange rate is not its policy mandate; the Treasury is in charge of exchange rate policy even though it has no tools to affect the exchange rate. Thus, targeting the dollar is not part of the Fed’s Congressional mandate and could create legal trouble if it becomes an official policy goal.[1] Second, an open policy to weaken the dollar could trigger a currency war reminiscent of the 1930s. Still, if the Fed is successful in weakening the dollar (see below for more on this topic), it will reduce policy stimulus for the rest of the world, especially in Europe and developed Asia.

The JPY has strengthened considerably in recent weeks despite the BOJ’s foray into negative interest rates (NIRP). The impotence of BOJ policy suggests that Fed policy is the primary driver of exchange rates in the current environment. First, a look at the JPY/USD exchange rate:

This shows the exchange rate in JPY per USD on an inverted scale. PM Abe took office in late 2012 and began Abenomics, which was a set of policies designed to boost Japanese economic growth and inflation. One of the primary tools was currency weakness. The JPY weakened in two phases, falling initially from 78 ¥/$ to over 100 ¥/$, and then, after additional stimulus, the currency took another leg down in 2014. The latter drop was more likely due to a strengthening U.S. economy and expectations of the end of Fed monetary accommodation. In January of this year, when the BOJ announced NIRP, the currency weakened (see arrow) but that drop failed to hold. Since then, the JPY has steadily strengthened. This is profoundly bad news for the Japanese economy. The forex markets are going to force some sort of reaction from the Abe government but its most effective tool, intervention, will be very controversial given that we believe the FOMC is deliberately trying to weaken the dollar. What makes it even worse is that such a move would become political fodder for the U.S. presidential primary candidates who are leaning against globalization.

Overall, the JPY could have a lot further to strengthen.

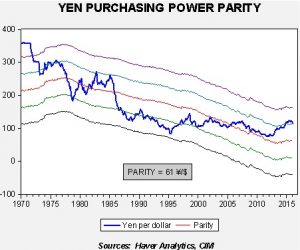

This chart shows a purchasing power parity valuation mode of the JPY/USD, which uses the ratio of inflation rates to value the exchange rate. The theory suggests the economy with lower inflation should have a stronger exchange rate. Because Japan is deflating, the parity rate is much stronger than the current exchange rate; in fact, at current rates, the JPY is a full standard error weaker than forecast. Although we don’t expect the Abe government to allow the JPY to continue to strengthen without a fight, the general undervalued nature of the JPY may make it difficult to prevent the strengthening trend from continuing unless the Fed moves to tighten soon.

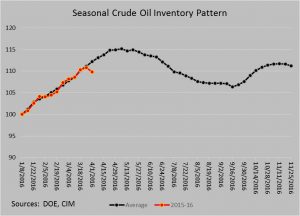

We had a surprise draw in crude oil stocks yesterday which was clearly bullish for crude oil. A decline this time of year is unusual and may portend a lower seasonal peak. However, Bloomberg is reporting that there are pipeline problems affecting Canadian exports to the U.S. which led to the unexpected draw in stockpiles. If the problems are fixed this week, we will likely see a surge in imports next week to make up for this week’s draw. This is probably why oil prices have not been able to follow through this morning.

China’s forex reserves rose $10 bn in March, rising to $3.213 bn. Although this is a positive number on its face as it suggests that capital fight might be easing, the market reaction has been rather modest. We will probably need to see a couple of months of reserve stability before we can declare that the PBOC has successfully contained the seeming panic of capital outflows.

Finally, the ripple effects from the Panama Wikileaks disclosures continue to mount. Iceland’s government has been rocked by the revelations, with the PM resigning and the finance minister coming under fire. Britain’s PM is catching flack for his family’s use of offshore accounts and the U.S. Treasury is apparently looking into whether the account violates sanctions against Russia. President Putin apparently has it figured out—the leaks are a Western plot to undermine the Russian state. On the topic of Russia, the FT is reporting that Putin is forming a National Guard that will be completely under his control. The belief is that this body will be mostly for civil order, suggesting Putin is becoming worried about rising protests against his regime as the economy stumbles.

______________________

[1] It should be noted that other central banks do have a forex mandate. The ECB is given the task of currency stability (although to date that hasn’t been defined), and the Hong Kong monetary authority’s only real job is to maintain the USD/HKD peg.