Asset Allocation Weekly (July 30, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

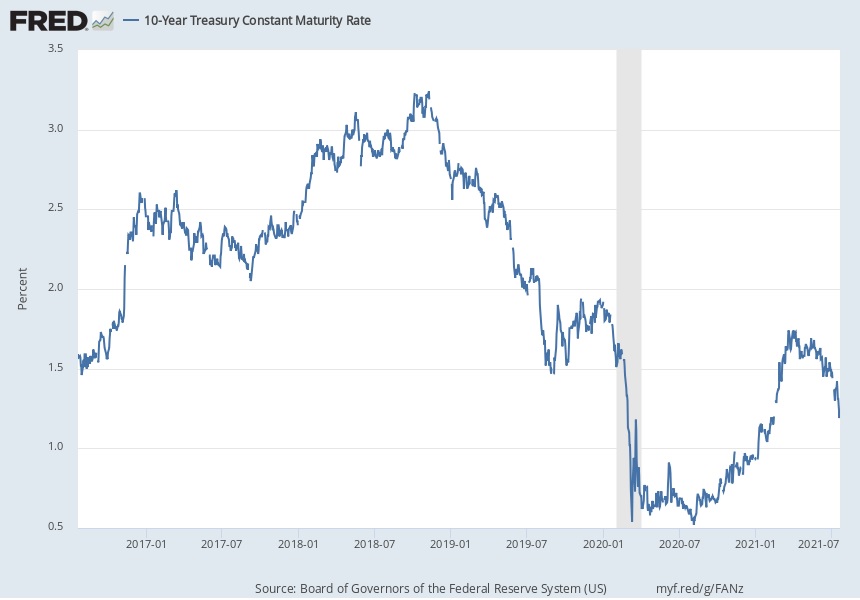

One of the key developments in financial markets recently has been the quick rebound in bond prices and the associated drop in yields. As investors started to sense faster economic growth and the prospect of rising inflation in the first quarter, they eagerly sold down their bond holdings, driving yields higher. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note jumped from 0.92% at the end of 2020 to an intraday high of more than 1.75% in late March (see following chart). Since then, however, bond buying has gradually strengthened again, and yields trended downward throughout the second quarter. Even when the Federal Reserve surprised markets in mid-June by hinting that the next interest rate hike might come by 2023, the resulting bond sell-off and yield jump was quickly reversed. In July, investors began buying bonds and driving down yields even faster, with the 10-year Treasury yield falling below 1.13% on July 19. This report looks at why yields are falling again and whether the downtrend is likely to continue.

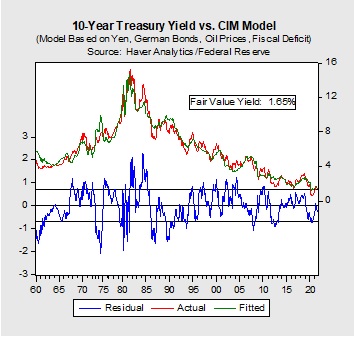

It’s one thing to know where yields have been; it’s quite another thing to understand where they should be and where they may be going. To get at that issue, our bond model estimates where the 10-year Treasury yield should be based on several variables. The most important variables are the Fed’s “fed funds” interest rate and, as a proxy for inflation expectations, the 15-year average of the yearly change in the consumer price index (CPI). Other variables in our model include the yen/dollar exchange rate, oil prices, German Bund yields, and the U.S. fiscal deficit scaled to gross domestic product (GDP). As shown in the chart below, the jump on bond yields early this year merely brought the 10-year Treasury yield up to the fair value estimated by our model. With the recent rebound in bond prices, yields have again fallen below their fair value, which the model currently puts at 1.65%.

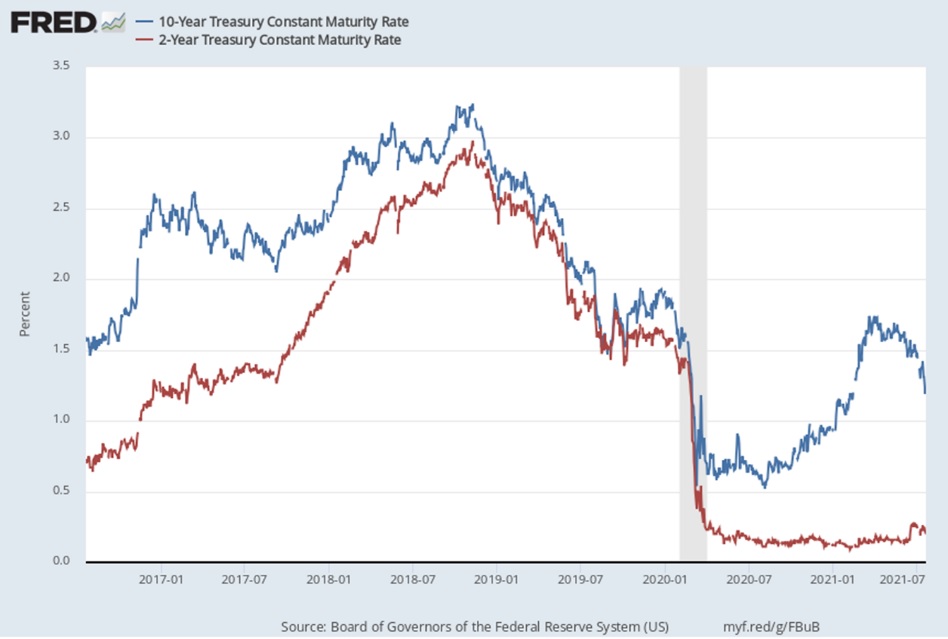

In other words, bonds once again look expensive―not as expensive as at the beginning of 2021, but enough to suggest bond investors see reason for caution regarding monetary policy and economic prospects. Many investors think the Fed will eventually tighten monetary policy just enough to smoothly bring down today’s high inflation rate. A less benign view among other investors is that the Fed might tighten policy too soon or too quickly. Those investors are worried about a policy mistake that could trip up the economic recovery and produce another recession. Still other investors think longstanding structural factors such as globalization and population aging will eventually reassert themselves and push down growth and inflation to the levels seen before the coronavirus pandemic. Such an environment of rising interest rates in the near term coupled with an eventual moderation in rates is consistent with the recent flattening in the yield curve. For example, the chart below shows how the yield curve, represented by the difference between the 10-year and the two-year Treasury rates, has changed recently.

In any case, we think our model’s call for higher interest rates should be respected, especially given the risk that inflation could stay high for longer than anticipated and gradually push up longer-term inflation expectations. We note that the 15-year average of CPI inflation that serves as a proxy for inflation expectations in our model is just under 1.90%. Other measures of inflation expectations, such as consumer surveys and the difference between nominal and inflation-protected bond yields, point to even higher future inflation. Even if the 10-year Treasury yield rebounds in the near term, we still believe it probably wouldn’t go much past 2.00%, but the risk of rising yields (and falling bond prices) has prompted us to reduce our exposure to longer-term bonds in several of our strategies for the third quarter.