Asset Allocation Weekly (August 6, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

In last week’s report, we updated our views on long-duration Treasuries, using our standard 10-year T-note model. This week we are going to examine the impact of policy on long-duration Treasuries.

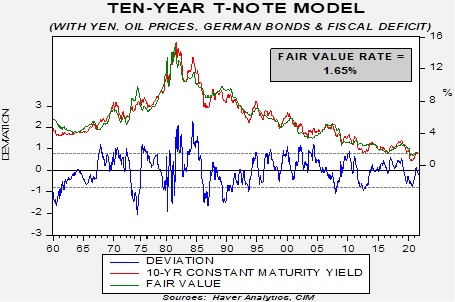

First, let’s start with the model.

The two most important variables in the model are fed funds and the 15-year average of the yearly change in CPI. The latter acts as a proxy for inflation expectations. We add the yen’s exchange rate, oil prices, German Bund yields, and the fiscal deficit scaled to GDP. So, there are two policy variables in the model, fed funds and the fiscal deficit.

A truism that has developed in recent years is that divided government is good for financial markets because different parties in the White House and Congress means it is harder to enact major legislative changes. To test this thesis, we created a binary variable that signaled if one party controlled the legislature and the executive branch, or not. When we added the variable to the model, it was not statistically significant, nor did it change the model’s forecast.

Regression models are sensitive to initial conditions; simply put, where you start a model in time has a notable impact. Jim Bullard, the president of the St. Louis FRB, likes to think of eras with certain conditions as “regimes.” Applying Bullard’s notion of regimes, we next broke down the data by attitudes toward government. In other words, the truism that divided government was good for financial markets may not have always been true. To test this idea, we first ran the model from 1960 to 1982; attitudes toward the government were once positive. For the generation that lived through WWII, the government was not seen as an obstacle to overcome but as a support. The model did change; the government variable was statistically significant and showed that when the same party held both branches of government, yields were 50 bps lower. From 1983 to the present, the government variable was also statistically significant, but the sign changed. Unified government increased bond yields by 31 bps. We propose that the Reagan/Thatcher revolution changed the views of government compared to the earlier era.

Another interesting factor is that in the earlier regime, deficits were bearish for bonds; in other words, a deficit led to higher yields. In the current regime, deficits are less significant but the sign on the coefficient changed here as well. Deficits now lead to lower yields, although the impact is quite modest.

Finally, the model from 1983 has a current fair value of 1.70%, which is a bit higher than the full model shown above. Thus, its fair value is close enough to give us confidence that it is giving proper signals. The other important takeaway from this analysis is that if the Democrats lose one of the houses of Congress in November 2022, caeteris paribus, the fair value yield would decline by nearly 50 bps.