Asset Allocation Weekly – Globalization Isn’t What It Used to Be (October 15, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep…But, most important of all, he regarded this state of affairs as normal, certain, and permanent, except in the direction of further improvement.

— John Maynard Keynes

Over the last 30 years, we have grown accustomed to all the benefits of globalization. During this time, goods prices not only became more stable, but the delivery of goods was fast and reliable. However, this hasn’t been true over the last few months. Since the start of the pandemic, countries that rely heavily on global supply chains have struggled to receive goods from other countries. Supply constraints have made it difficult for firms to meet domestic demand. This dynamic has put the Fed in a bit of a quandary as it struggles to determine the path of policy. In this report, we discuss how supply chain disruptions have led to the recent rise in inflation and how the Fed might respond if prices remain elevated.

A key element to globalization is stability. In a stable world, firms are better positioned to absorb supply shocks. When the world is stable, firms are able to deal with isolated supply disruptions by going to different suppliers for goods or by finding cheaper alternatives. For example, when the price of coal goes up, firms generally purchase more natural gas and vice versa. Additionally, when the swine flu led to a shortage of pork products in China, the Chinese began importing pork from the U.S. In a stable world, shortages in one part of the world can be made up by an increase in production in other parts of the world. However, the dynamic changes when there is a universal shock like a war or pandemic.

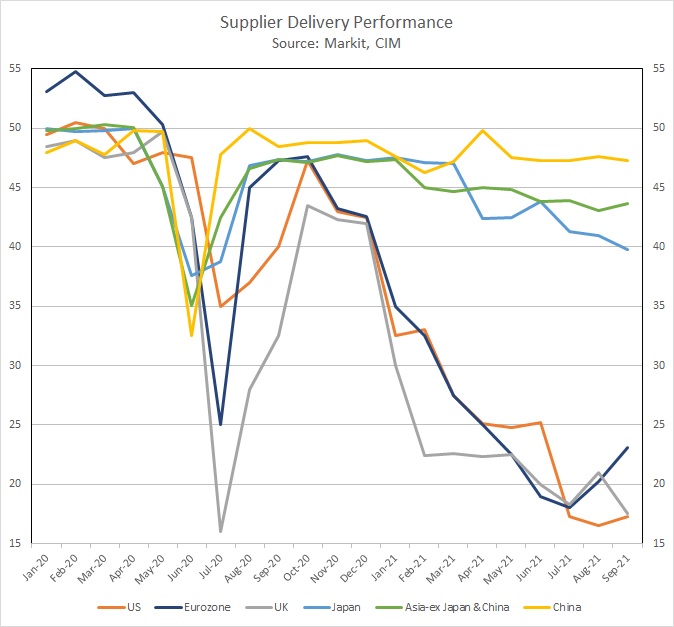

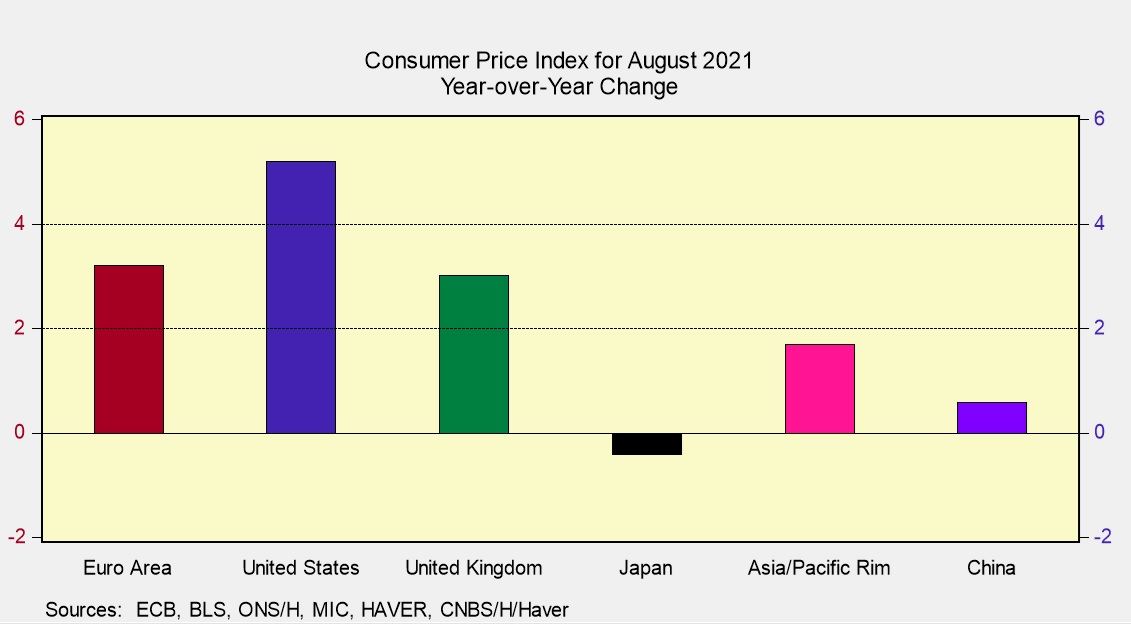

The pandemic has shown that globalization is ill-suited to deal with global supply shocks. The chart above shows that over the last few months, the U.S., U.K., and Eurozone, each of which relies heavily on outsourcing from Asia, have seen a steep decline in their supplier delivery performance. However, Asian nations, where there is less dependence on outsourcing, have seen their supplier delivery performance remain relatively stable. Furthermore, there does seem to be an inverse correlation between supplier delivery performance and inflation. The U.S., U.K., and Eurozone are all experiencing increases in inflation not seen in their respective countries in more than a decade. Meanwhile, Asian nations have seen their inflation fall below the standard target of 2%. The regional discrepancies between the rates of inflation highlight the impact the pandemic has had on global supply chains.

We suspect that as long as supplier delivery performance remains slow, it will be difficult for inflation to fall anytime soon in the U.S., U.K., and Eurozone. As a result, the Federal Reserve will face increasing pressure to react to higher inflation. After all, a lack of response would threaten its credibility and might undermine its independence. There are elements of the financial markets that would like the central bank to raise rates in order to contain inflation, while populist politicians would like it to maintain easy monetary policy to ensure that wages keep rising and firms keep hiring. Angering the former could result in investors losing faith in the dollar, while angering the latter could lead to more political scrutiny.

Additionally, there is still the chance that raising rates in this environment may lead to undesired outcomes. Although higher rates could lower inflation by decreasing demand, they could also make it more expensive for firms to expand supply and maintain employment. The former may be the expected outcome, but the latter still presents a risk. Given the unpredictability of this pandemic, it is difficult to determine which outcome will prevail. As a result, raising rates may increase the likelihood of recession. This should prevent the Fed from raising rates sharply.

In conclusion, the steep slowdown in supplier delivery performance suggests that inflation will likely remain higher for longer. There will be increasing pressure on the Fed to tighten policy or risk undermining the central bank’s inflation credibility. At the same time, much of the pandemic’s impact on supply chains is temporary and price pressures should be mitigated as the pandemic is resolved. We expect the Federal Reserve to slow its balance sheet expansion initially and take a wait-and-see approach to raising policy rates. The risk of moving too soon is that it raises the possibility of needlessly stalling the improvement in the labor markets. The risk of moving too late could undermine confidence in the dollar and raise inflation expectations. The chances of a policy error are rising, and we will be monitoring the path of policy closely in the coming months.