Weekly Energy Update (July 21, 2022)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

It appears that oil prices are settling into a broad trading range between $125 and $95 per barrel.

(Source: Barchart.com)

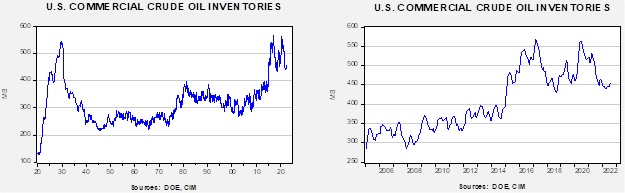

Crude oil inventories fell 0.5 mb compared to a 1.0 mb draw forecast. The SPR declined 5.0 mb, meaning the net draw was 5.5 mb.

In the details, U.S. crude oil production fell 0.1 mbpd to 11.9 mbpd. Exports rose 0.7 mb, while imports fell 0.2 mbpd. Refining activity declined 1.2% to 93.7% of capacity.

(Sources: DOE, CIM)

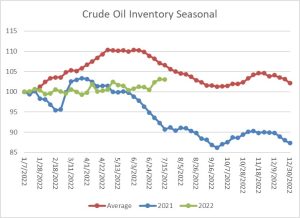

The above chart shows the seasonal pattern for crude oil inventories. It is clear that this year is deviating from the normal path of commercial inventory levels. Although it is rarely mentioned, the fact that we are not seeing the usual seasonal decline is a bearish factor for oil prices.

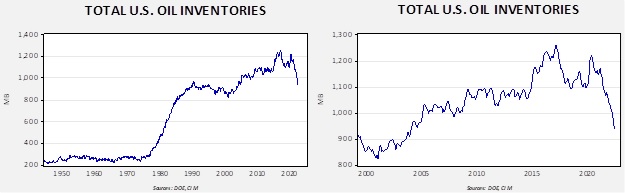

Since the SPR is being used, to some extent, as a buffer stock, we have constructed oil inventory charts incorporating both the SPR and commercial inventories.

Total stockpiles peaked in 2017 and are now at levels last seen in 2004. Using total stocks since 2015, fair value is $102.12.

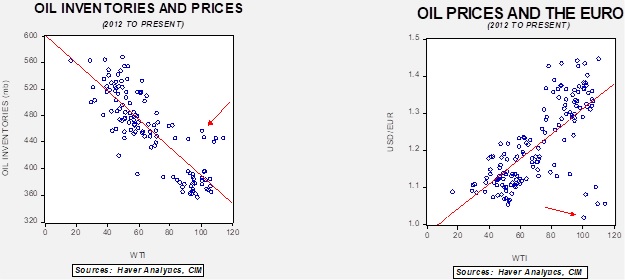

With so many crosscurrents in the oil markets, we are beginning to see some degree of normalization. The inventory/EUR model suggests oil prices should be around $65 per barrel, so we are seeing about $35 of risk premium in the market.

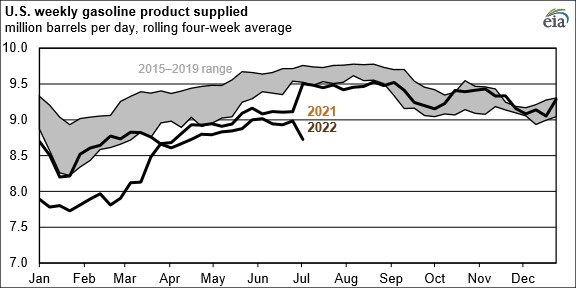

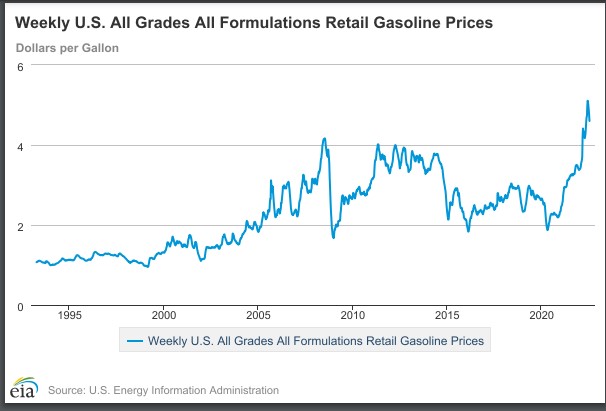

Gasoline Demand

Gasoline demand has turned lower. Although high prices may have been the culprit, gasoline demand was price insensitive for most of market history. However, with the advent of work from home and increasing retirements, gasoline prices may have become more sensitive.

This easing of demand does appear to be lowering gasoline prices.

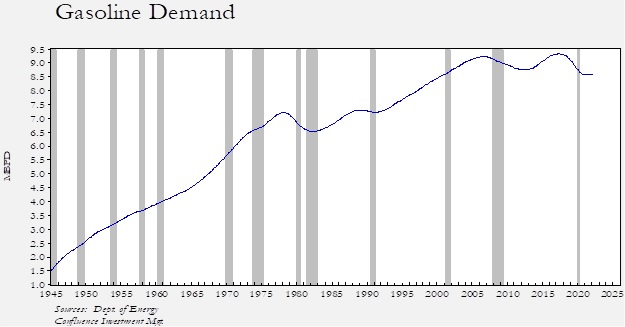

In observing the long-term history of gasoline demand, we note that by stripping out the monthly variation with a Hodrick-Prescott filter, it appears that underlying demand is weakening.

Gasoline demand rose strongly from the end of WWII into the mid-1970s, but the Iran-Iraq War’s price spike and its gasoline shortages led to a drop in demand that lasted about a decade. Demand rose again in the early 1990s into the Great Financial Crisis, but since then demand has been mostly sideways. This would suggest a secular change in gasoline demand is in place, which signals persistently weak demand. Thus, the current slowdown may be part of a larger trend.

In observing the above demand chart, it does beg the question, “Why would anyone build additional refinery capacity if demand isn’t set to grow?”

Market news:

- Later this week, we will find out if Russia will restart the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, which has been closed several weeks for maintenance. Early signs are not comforting, as some European deliveries were not made by Russian producers. There are also reports of Russian suppliers failing to offer supplies to European buyers. It does appear that Russia will restart the pipeline as President Putin indicated that Russia would “fulfill it’s commitments” but warned that flows might fall short if additional sanctions prevent maintenance from being performed. This looks like a quid pro quo – Putin will open flows if sanctions are reduced. Although not directly related, the EU has agreed to ease sanctions on Russian banks to allow for food export payments[1]. In the meantime, the EU is starting to prepare for uncertain gas flows by establishing procedures to shut off gas to industrial users and encouraging other users to conserve. The IEA has offered recommendations as well. Although we are worried about supplies now, the real concern will be in wintertime. If Russia reduces flows of gas when it’s cold, the EU could be in deep trouble.

- A number of sources have suggested that a Russian gas cutoff would have devastating economic effects for Europe. The German industrial sector would be especially at risk. The German chemical industry is already warning that it cannot cut back further without closing completely. The IMF warns the EU economy is at risk for a Russian gas embargo, and the European Commission is estimating a 1.5% decline in GDP. Hungary and Italy are the EU nations at most risk from a loss of Russian natural gas.

- Although there has been widespread accusations of bad behavior by the oil industry to account for high product prices, the reality is, simply, there isn’t enough refining capacity. This isn’t just a U.S. problem; it’s global. The reasons are complicated. For one, for a long time, the industry’s profit margins have been lackluster. The facilities are large, smelly, and potentially dangerous, so not wanting it in one’s backyard is understandable. The lack of investment and the aging out of facilities, however, has led not just to tight product stocks but diminishing supplies of petrochemicals.

- Another factor is that Russia’s refinery industry needs Western expertise to function, and China has been closing rudimentary “teapot” refineries, leading to lower production and exports. These factors are further crimping global product supplies.

- An often overlooked factor is that refineries use natural gas to produce energy products. Rising natural gas prices, or in the case of Europe, outright shortages, will also crimp gasoline and distillate production.

- A South African refinery was forced to shut down operations due to the lack of crude oil.

- The price chart at the top of this report suggests a weakening crude oil market. However, that may be more of a reflection of the speculative community than physical oil traders. The latter indicate that there are large premiums between cash markets and futures benchmarks, suggesting the physical market remains tight. If this persists, the futures markets will eventually reflect that higher price.

- Australia is a significant coal and natural gas producer, and yet, is facing a serious energy crisis. An ill-conceived electricity pricing structure, which underpriced electricity, led to outages. Adding to pressure is an incomplete attempt to substitute renewables for coal and gas electricity generation. Australia may be forced to restrict exports, which could hamper East Asian economies who rely on this energy source.

- China’s Zero-COVID policy has led to a drop in LNG imports as heavy industry slows. The new variants are increasing infections across China and may result in new lockdowns. However, that didn’t help Japan, who just paid a record amount for an LNG delivery.

- The fire at the Freeport LNG facility has led to a decline in demand; interestingly enough, production has also slipped. However, once the facility returns to service (probably in September) the supply demand balance will become much more bullish for natural gas.

- A German bar, seeing shortages of cooking oil, offered beer for oil.

- A recent report suggests that, even with record high prices, world oil reserves have declined by 9%. There appears to be ample supplies, but the trend is disconcerting.

Geopolitical news:

- President Biden made it to the Middle East last week. The trip was a mixed bag of sorts. On its face, the president was trying to normalize relations with a key ally, the KSA. The U.S. has been concerned about Chinese and Russian encroachment in the region and is always worried about Iranian actions. The U.S. is working to support an Israeli/Gulf Nation coalition to contain Iran. We note that Russian President Putin has been in the region this week, visiting Turkey and Iran. However, President Putin’s trip was prompted by high oil prices. On that front, we doubt much will happen. The consensus is growing that the Arab oil producers are near capacity. Biden was warmly greeted in Israel and there was some movement to improve relations between Israel and the Arab Gulf states. But the odds of getting appreciably more oil isn’t likely, despite comments suggesting otherwise.

- It should be noted that in the aftermath of the meeting, the Saudis indicated they would work within OPEC+ for output decisions.

- The question of Russian oil continues to vex the West. Cutting off oil flows would reduce Russia’s income, but it is clear that Moscow is still finding buyers, many of whom are in Europe. Russia has also rebalanced oil flows, sending more to China and India. Simply put, there is little evidence to suggest sanctions have reduced Russia’s oil revenue. The classic economic response to such a problem is to implement a tariff, which would raise the price of Russian crude, making it less attractive to buyers. Either Russia would be forced to stop selling crude to the tariff-implementing nations or would need to cut its price to world levels by the amount of the tariff, reducing Russia’s revenues. Treasury Secretary Yellen offered up the tariff idea, but it went nowhere. She then proposed a price cap. If a large enough group could come together, they could set a price that would reduce Russia’s revenue. In theory, the price could be near marginal costs, which would make it reasonable to Russia to continue producing. At first glance, this proposal seems wanting; after all, if a buyer could simply set the price, there is little need for markets. However, there is a case to be made that if enough buyers participate, they could dictate a price. Obviously, Russia could simply decide to stop selling oil, but that would be risky. If wells are shut in, it’s not likely they will be restarted, and this action could lead to a permanent loss of global capacity. In addition, Yellen is proposing a price that would not generate losses for Russia, so she claims they should accept it.

- Interestingly enough, China, a key Russian ally, has not rejected the proposal outright.

- So, what could go wrong? Such arrangements have been tried throughout history. The U.S. had a scheme where oil had different prices depending on when it was produced; it simply led to regulation evasion.[2] It’s not hard to see how Russia could game this arrangement. Let’s say the price is $50 per barrel. Russia will sell you the oil at the price if you agree to sell something else to them below market prices, e.g., semiconductors.

- Meanwhile, we are seeing energy flows adjust to sanctions. China is shifting oil imports to Russia, reducing flows from Saudi Arabia. Given the price difference, this makes sense. Saudi extra light crude is trading at a nearly $40 per barrel premium to the Urals benchmark; prewar, this difference ran about $5 per barrel. We have seen, in the past, that the Saudis would try to defend their market share in key markets. For example, in the late 1990s, the price war between Venezuela and Saudi Arabia was over the U.S. market. We doubt such a conflict will emerge here for two reasons. First, the KSA is careful not to sour relations with Russia. Second, we don’t think the kingdom has the excess capacity to take such action. In addition, it’s not just crude oil, as China is buying all types of energy from Russia.

- One of the reasons the U.S. is so keen to set up this price-cap system is to try and thwart an EU proposal to deny Russian oil tankers’ insurance. Although China, Russia, India, or some other buyer could ensure the vessel, EU and British insurance firms provide 85% to 90% of all policies. Some owners won’t sail without insurance from these sources and the Suez Canal Authority won’t accept any insurance other than EU or British policies. The U.S. fears that if the EU plan goes through, Russian oil will become impossible to source and prices could soar. The price cap is designed to postpone the insurance ban.

- Libya Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, wants to fire the head of the nation’s National Oil Company, Mustafa Sanalla. Libya has been rocked by civil war ever since a coalition of EU nations and the U.S. ousted Moammar Gaddafi. The nation is currently divided, with both sides fighting over control of oil revenues. This fight has led to insecure oil flows which occasionally reduces global supplies.

Alternative energy/policy news:

- Heat waves in Europe and the central U.S. dominated the news. In the former, wildfires have developed in several nations. The U.S. has seen an uptick in fires as well. Texas has been on the brink of blackouts for most of the summer. Interestingly enough, solar power has been one of the factors that has allowed power to stay on in the Lone Star State.

- Britain is facing record heat this week, leading the government to declare a national emergency. There is evidence to suggest that as the climate changes, jet streams are adjusting, leaving Europe unusually hot and dry. Areas that are usually cool are facing record heat. As we saw in the U.S. Pacific Northwest last summer, areas not usually hot suffer greatly from heat waves. In the U.K., for example, only about 5% of homes have air conditioning. Until recently, it was never hot enough long enough to warrant the investment. In addition, homes are designed to hold heat during the cold winter, making them even more of a problem during an unusually hot summer. Thus, not only are European nations facing excessive heat, but wildfires too, with flames developing even within London.

- As one would expect, fans and air conditioner demand is soaring in the U.K..

- The RAF has halted flights from its largest air base as the runway tar softened in the heat.

- The heat has killed more than 1,700 people in Spain and Portugal.

- In the U.S., it is estimated that 40 million people are at risk from the current heatwave.

- The question of climate change is politically charged. However, the majority of Americans, in a recent poll, note that weather extremes are affecting them. It’s not that people don’t notice the climate change, it’s more likely that they don’t trust policymakers to fairly allocate the costs of mitigation.

- China is reporting that high temperatures are adversely affecting industrial output. The heat is increasing strains on the electrical grid.

- At long last, Japan has finally relented and is restarting nuclear reactors. The reactors were closed after Fukushima. Earlier this month, the government announced the return of five reactors. It has decided that, by winter, four more will be restarted, bringing the total to nine.

- We continue to closely watch developments in geothermal power.

- Renewable energy firms are starting developments on old coal-fired generation sites because they are connected to the grid.

- This report lays out the path to replacing fossil fuels with renewables. One of the key findings is that regulation is hampering the efforts.

- One issue that bears watching are allegations that some solar panels are being manufactured by Uyghur forced labor.

- Carbon capture continues to attract investment; a trade group has formed to further boost the industry’s profile.

- Treasury Secretary Yellen is calling for an end to dependence on China for rare earth metals. The problem for mining, but especially processing, rare earth metals is the environmental costs. The creation of these metals is especially “dirty”. So, if the refining is going to occur in the U.S., it will be interesting to see where it occurs.

- As EVs become more popular, the market for home charging stations is heating up.

[1] This is part of a deal to end the blockade on Ukraine grain, but it is still uncertain if the blockade will actually be lifted. The details are daunting as the waters around Odessa are heavily mined and it isn’t clear if Russia will allow NATO minesweepers to clear a shipping channel. It’s also not obvious that Ukraine will trust the Russians to clear the mines either.

[2] Marc Rich was to be indicted for this and other embargo evasions with Iran. He fled to Switzerland.