Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The Importance of the Policy Mix (March 13, 2023)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

Based on the strong U.S. economic data so far this year, investors have again become worried that the Federal Reserve will continue to hike interest rates aggressively and keep them high for a prolonged period. We agree that is a significant risk, and the rate hikes to date are a key reason why we continue to think a recession will take hold later this year. However, it’s important to remember that such a scenario doesn’t rely solely on economic trends or monetary policy. We need to consider the whole policy mix, or monetary policy combined with all the other aspects of economic policy. For example, the Fed’s rate hikes may need to be more aggressive to tackle inflation if they aren’t matched by anti-inflation measures in fiscal policy (such as tax hikes or spending cuts that help reduce demand), regulatory policy (such as eliminating rules that raise the cost of doing business), industrial policy (such as promoting the expansion of new industries to boost product supply), and perhaps even social policy (such as education and workforce policies to increase the labor supply). Likewise, if Fed officials get cold feet and surrender their monetary tightening too soon, the inflationary impact of that pivot could be more pronounced than expected if the overall policy mix is relatively loose.

The successful fight against U.S. inflation at the beginning of the 1980s illustrates how strategists and investors sometimes forget how important the policy mix can be. Many economists, investment strategists, and even Fed officials themselves insist that it was simply tight monetary policy under former Fed Chair Paul Volcker that finally broke inflation’s back. In contrast, we believe that deregulation and expanding globalization during that period were probably just as instrumental in bringing down inflation and re-establishing the dollar’s value. To understand where inflation, asset prices, and the dollar are going in the coming years, we need to consider the current inflationary or restrictive U.S. non-monetary policies. We judge that those non-monetary policies are relatively loose at this time. Therefore, even if there is a risk that the Fed may tighten monetary policy too much and for too long, we think there is also a significant risk that the Fed may pivot to looser policy too soon.

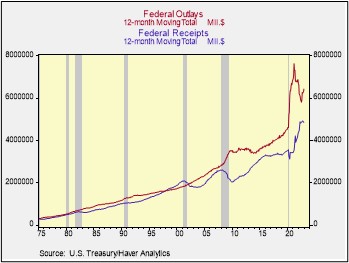

The most important non-monetary policy is fiscal policy, demonstrated by the size of the federal budget deficit. As shown in the following chart, federal outlays ballooned during the pandemic to cushion the blow to the economy, even as revenues initially fell slightly. In the post-pandemic economic recovery to date, federal spending has fallen and receipts have risen, but the disparity between them remains relatively large. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal deficit this fiscal year will narrow to 5.3% of gross domestic product, matching its 20-year average. However, federal outlays have recently begun rising again, while receipts have plateaued. The deficit has, therefore, started to expand again, and the CBO forecasts that unless there is a change in law, it will keep expanding as a share of GDP for at least the next few years.

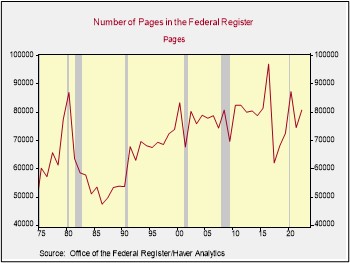

It is more difficult to measure how restrictive or loose regulatory policy is currently, but we think one indicator is the number of pages in the Federal Register, the government’s official compendium of rules and regulations. The chart below shows how the number of pages in the register has fluctuated over the last several decades, beginning with the big spike in pages during the high inflation of the 1970s, the big drop during President Reagan’s deregulation program, and the return to relatively high numbers over the last couple of decades. The page count currently stands above its 20-year average, and we see little sign that the federal government will deregulate the economy anytime soon. It is true that conservative judges on the Supreme Court have recently attacked major regulatory initiatives using a new “major questions doctrine,” but even if those rulings were to continue, it would still take time to see a significant loosening of regulations that would boost supply, reduce business costs, and ease inflation.

Other policy aspects seem to offer little hope for reduced inflation pressures going forward. For example, supply is likely to be constrained and rendered more expensive by deglobalization (a form of re-regulation that cuts off efficiency gains from international trade) and near-shoring (a form of industrial policy that builds relatively more expensive, but more resilient, supply networks closer to home). Meanwhile, our read of political trends suggests that there is no great move toward social policies that might significantly expand the labor force.

In sum, investors probably need to pay more attention to the thrust of the overall economic policy mix and remember that U.S. non-monetary policies are currently rather inflationary in nature. Expanding fiscal deficits, onerous regulations, deglobalization, and the promotion of more resilient supply chains will likely translate into upward pressure on inflation. Therefore, if the Fed unexpectedly abandons its current tightening program and pivots too early to looser monetary policy, it could spark panic regarding the path of future inflation. The result would likely be a sell-off in bonds, big headwinds for equities and other risk assets, and a sustained pullback in the value of the dollar.