Daily Comment (August 3, 2023)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA, and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] | PDF

Good morning! Today’s Comment will explore three key topics: the U.S. deficit, central bank policy, and the U.K.’s post-Brexit economy. First, we will discuss the U.S. deficit and what it may mean for bond yields. Second, we will explain why other central banks may follow Brazil as it moves away from tight monetary policy. Finally, we will discuss why the Bank of England may be helping boost the British pound.

Downgrade Trouble: The downgrade by Fitch Ratings of the U.S.’s credit rating and the announcement of another round of debt issuance has investors concerned about the country’s ballooning deficit.

- On Wednesday, the U.S. Treasury Department announced that it would auction off $103 billion in new bonds this quarter in order to resolve a shortfall between tax revenue and government spending. The move has made investors uneasy, as it is unclear whether the market is capable of absorbing such a large amount of issuance. This report comes a day after Fitch Ratings Agency downgraded U.S. credit ratings from its top level. Making matters worse, lawmakers broke for their August recess earlier this week without coming to a resolution on funding the government for the next fiscal year. This has raised concerns about the possibility of a government shutdown in October, which would further strain the U.S. economy.

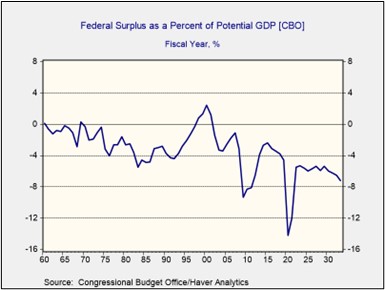

- Investors are worried that partisan gridlock in Washington will prevent lawmakers from adequately addressing the U.S. budget deficit. This uncertainty has led to a sharp rise in the 10-year Treasury yield, which has risen nearly 20 basis points since August 1. Higher yields threaten to push up borrowing costs for firms, which could weigh on corporate earnings and stock prices. The S&P 500 index has dropped almost 1.7% since the Fitch downgrade. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the government deficit is expected to deteriorate over the next 10 years.

- In 1994, President Clinton’s advisor James Carville once quipped, “that if there were reincarnation, [he] would like to come back as the bond market” because then he could “intimidate everybody.” This week’s market reaction to U.S. debt woes is a good example of how relevant his words are today. That said, we believe that in the long run, yields on long-duration Treasuries will have to rise as investors adjust to a new normal with higher inflation volatility and less Federal Reserve involvement. This should lead to slower economic growth as higher borrowing costs tend to reduce consumption.

Who’s Next? The Central Bank of Brazil was one of the first to raise interest rates in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is now one of the first to pivot away from hawkish policy.

- Brazil’s central bank cut its benchmark interest rates by 50 bps to 13.25% on Wednesday. The decision came amid pressure from President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and his economic team to ease monetary policy in an effort to boost the economy. Although the unemployment rate remains well below the country’s long-run trend of 9.5%, a gauge for gross domestic product showed that economic activity dropped 2% in May. Businesses and consumers will likely welcome lower rates. However, it will be the first test to see if the lower rates will lead to a return to inflation.

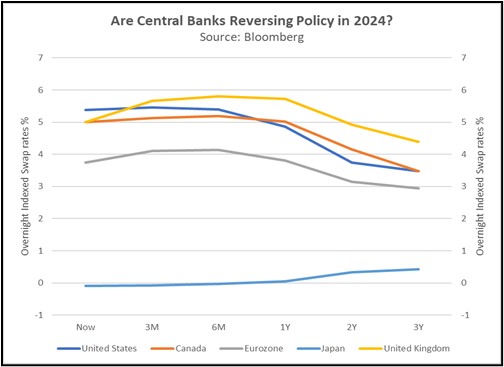

- Other central banks are expected to follow suit, as overnight indexed swaps rates suggest that benchmark interest rates will decline in most major economies by 2024. The switch to monetary easing is likely a reflection of a global decline in price pressures. The IMF expects global inflation to fall from 8.7% last year to 6.8% in 2023. Additionally, central bankers are facing pressure from politicians to ease monetary policy, as the high-interest rates are harming households. In the U.K., the Bank of England is on the verge of triggering a potential mortgage crisis; meanwhile, higher interests rates have disproportionately hurt homeowners in southern Europe who are now relying on savings to make monthly payments.

- Generally speaking, central banks in developed countries have made gradual changes when raising rates and more dramatic cuts when lowering them. However, this time may be different. Advanced economies have proven to be more resilient than experts expected at the start of the year. This could lead policymakers to be more cautious with easing monetary policy, as they may be concerned about a return to higher inflation. This approach is typical in emerging markets where inflation is more volatile. This may mean that investors should be more cautious during this easing cycle than the previous one when deciding to add more risk to their portfolios.

U.K. Path: The Bank of England (BOE) may keep monetary policy tight in order to restore confidence in the British pound (GBP).

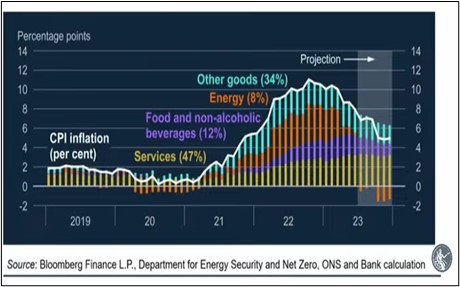

- The Bank of England raised its benchmark interest rates by 25 bps on Thursday to a 15-year high of 5.25%. This is the bank’s 14th consecutive hike and reflects its continued fight to bring inflation down toward its 2% target. During his press conference, BOE Governor Andrew Bailey predicted that July inflation has decelerated to around 7%, much lower than last year’s peak of 11%. He added that the central bank plans to continue to raise interest rates further as policymakers aim to push inflation down to 5% by the end of the year. The central bank now forecasts inflation to fall to 4.9%.

- The Bank of England does not seem to be willing to take its foot off the pedal. There were two policymakers within the BOE’s Monetary Policy Committee that pushed for a 50 bps hike in interest rates, with one vote for keeping rates unchanged. This voting breakdown suggests that British policymakers remain relatively more hawkish than their Western counterparts. While the heads of the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve suggested last week that they may be nearing the end of their hiking cycles, Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey offered no such reassurances. Instead, he maintained that “in order to get inflation back to target, [the BOE] is going to have to keep this stance of monetary policy.”

- After breaking away from the European Union, the United Kingdom will now have to prove that it can stand on its own. One way it may do this is by legitimizing the value of its currency. Over the last two weeks, the GBP has risen around 4% against the dollar, even as other peer currencies, as measured against the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY), declined about 3% in the same period. This divergence suggests that investors are confident that the Bank of England is willing to take steps to bring down inflation, even if it means causing economic pain. A strong GBP, particularly against major trading partners, will help to quell price pressures by making imports cheaper.

Fed News: Kansas City Fed has hired Jeffrey Schmid to take over as President and Chief Executive Officer. He is a former bank executive and has experience in bank regulation.