Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – Reflections on Earnings (November 20, 2023)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

The third quarter’s earnings season is coming to a close and, once again, earnings beat expectations. In this report, we will take a more in-depth look at S&P 500 earnings and overall corporate earnings.

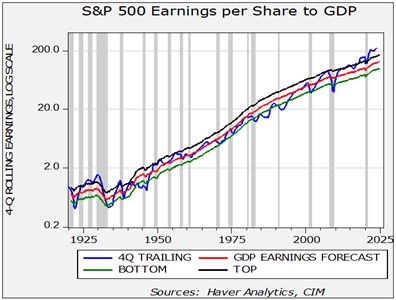

This chart examines S&P 500 earnings on a four-quarter trailing basis. We have regressed nominal GDP against earnings; the idea is that the red line on the chart should estimate the impact of economic growth on earnings. In other words, the red line reflects what part of earnings is explained by nominal GDP growth. The lines that bracket the red line represent a standard error from the forecast. One reason for owning stocks is to participate in the growth of the economy. When earnings are above the red line on the chart, it suggests margin expansion. There have been periods of outsized margin expansion. For example, from 1925 into 1929, earnings outpaced GDP by a wide margin. They also reached the upper line on a couple of occasions in the 1950s, but that level wasn’t reached again until 2007. It’s notable that once earnings recovered after the Great Financial Crisis, they then stayed elevated and even shrugged off the pandemic recession.

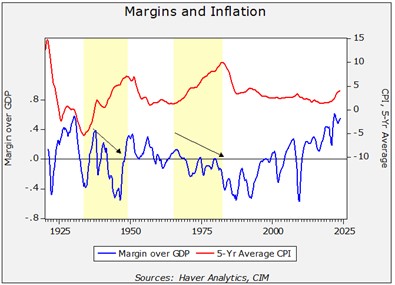

Why have earnings been so persistently strong? A likely reason is that firms have accumulated market power. That means firms don’t face competition and therefore have a greater ability to maintain profit margins. Often, these firms have monopsonistic or oligopsonistic power in the labor markets. When faced with rising input costs, firms can either depress labor costs through wage cuts or layoffs or pass on cost increases to consumers via higher prices. Unfortunately, there is no single variable that captures market power. However, observing the margins after GDP to the trend in CPI, the current environment does suggest market power.

The periods shaded in yellow show when the trend in inflation is rising. The margin measure is the residual from S&P 500 earnings not accounted for by GDP. The fact that margins are holding up while facing rising prices does suggest that firms enjoy market power. As the chart shows, margins tended to weaken during periods when the trend in CPI was rising.

The impact of market power over labor is also evident.

The above chart shows the labor share, which is defined as compensation relative to output. As the chart indicates, the labor share was mostly steady from 1949 into 2000. Although in this century, there was a definitive shift downward in the labor share. It has stabilized in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis, but it has not improved to its earlier levels.

This market power is likely due to three factors. First, globalization, which in its current form weds global markets with technology, has allowed firms to separate the design function away from production, giving firms the opportunity to source low-cost labor abroad. In the U.S., immigration-friendly policies tended to lift the labor supply. Second, anti-trust policy adopted the Bork Standard beginning in the mid-1980s. This legal theory postulated that if a company’s pricing policy didn’t adversely affect consumers, market combinations were not harmful. This policy led to larger firms that developed market power. Third, deregulation allowed for the rapid adoption of new technologies which lowered costs, but pricing power meant that these cost reductions would not necessarily be passed on to consumers.

The key question is whether this environment will persist. There is evidence to suggest that it won’t. First, globalization rests on a functioning hegemon providing global security and a reserve currency and asset. We have detailed in numerous Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Reports the ways in which America’s hegemony is under threat. As U.S. power wanes, conflicts become more common, leading to supply disruptions that tend to depress market power. Second, Lina Kahn, the head of the Federal Trade Commission (one of the bodies that approves mergers and acquisitions), is working to implement an earlier anti-trust standard which argues that size alone is an impediment to combinations. We doubt she will be initially successful, but now that the Bork Standard has been questioned, we expect the policy will erode over time, leading to greater competition. Finally, we anticipate that increased regulation, especially in terms of industrial policy (the government steering investment), trade impediments, and immigration restrictions will give labor power again. We are already seeing a wave of strikes that have had remarkable success, mostly due to the exit of baby boomers from the labor force. Over time, however, restricting immigration will play a role in boosting labor power.

Thus, we expect this period of remarkable profitability will end at some point. The trick is timing. It isn’t likely to happen immediately, but the conditions to reverse profitability are developing. These circumstances are something investors will need to monitor in the coming years. What should an investor expect to see as these margins narrow? Lower capitalization stocks, which don’t enjoy the benefits of market power to the same degree as larger firms, will probably outperform large caps.