Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – Who Wants US Treasurys? (February 20, 2024)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

Before August 2023, the Treasury’s quarterly refunding rarely raised eyebrows. Investors readily snapped up US debt, and announcements were largely ignored by markets. However, Fitch Ratings’ surprise downgrade of the US credit rating from AAA to AA that month, just days after a $6 billion increase in the planned quarterly debt issuance, sparked investor concerns. Now, the question looms: Will there be enough demand to absorb the growing supply of US debt?

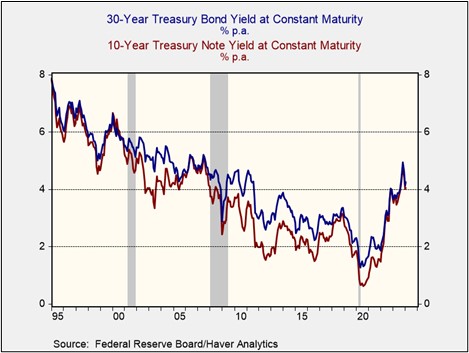

The downgrade by Fitch triggered a sharp rise in Treasury yields, especially long-term yields, which hit their highest levels since 2007. The 10-year and 30-year benchmarks spiked to multi-decade highs, reflecting lukewarm participation at Treasury auctions. Higher borrowing costs and weak auction participation sent the S&P 500 Index tumbling. In response to the market’s negative reaction, the Federal Reserve signaled an end to its hiking cycle and a potential cut in policy rates for the coming year, and the Treasury Department tilted its borrowing toward shorter-term maturities.

While the coordinated efforts of the Fed and Treasury successfully reduced borrowing costs and improved overall risk appetites, investors remained uncertain about the government’s plans to finance its burgeoning debt. This year, $8.9 billion of US Treasury bonds will mature, while the budget deficit is expected to be $1.4 trillion, meaning there will be $10 trillion of bonds coming to the market. Additionally, the Congressional Budget Office projects that the deficit could expand to $2.6 trillion by 2025. This leaves a gaping hole in financing, and without a significant change in market conditions, it is unclear who will step up to buy these bonds.

The US Treasury market boasts a unique blend of buyers, each with distinct goals. Central banks, the guardians of global monetary systems, buy Treasurys to secure their reserves and stabilize currencies. Similarly, pension funds prioritize stable, long-term income to fulfill their liability obligations. For the Fed, Treasurys become instruments of monetary policy, influencing interest rates and economic activity. Asset managers diversify their portfolios with these secure assets, reducing risk and volatility. Even households directly participate in holding a portion of the national debt, seeking a safe place for their investments.

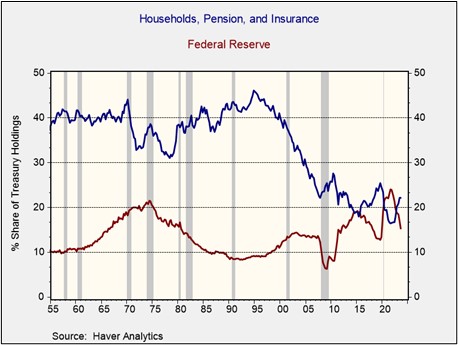

The Fed’s shift toward tighter monetary policy in 2022 and 2023 reshaped the allocation of Treasurys. By not rolling over its maturing Treasury holdings, the Fed is now absorbing less of any new supply. Simultaneously, interest rate hikes have incentivized some corporations and foreign central banks to moderate their holdings, creating a demand gap. Households, pension funds, and insurance companies have stepped in to fill this gap, becoming the primary buyers of Treasurys. However, the central bank’s recent suggestion that it will phase in monetary easing later this year introduces uncertainty about who will buy debt going forward.

The high concentration of interest-sensitive investors like households, pension funds, and insurance companies in the bond market raises concerns about the potential impact of future interest rate cuts. Lower short-term rates typically decrease the appeal of risk-free assets like long-term bonds, potentially dampening demand. Households seeking higher returns in an accommodative monetary policy environment may consider diversifying into riskier assets. However, while pensions and insurance companies hold a significant portion of Treasurys, their demand for longer-term bonds is limited by their need to match their obligations.

Historically, broker-dealers have played a key role in stabilizing markets by absorbing available assets, but they face constraints that limit their ability to act as the buyer of last resort when the Fed doesn’t step in and provide liquidity. Broker-dealers, unlike central banks, hold limited inventory as they are primarily focused on facilitating client transactions rather than large-scale asset purchases. This limited capacity restricts their ability to absorb significant volumes of assets during periods of stress. To compensate for the inherent liquidity risk involved in holding large inventories, broker-dealers would require higher premiums, therefore pushing up yields on Treasurys.

With limited demand from traditional buyers putting pressure on long-term Treasury yields, concerns have risen that the Fed may need to intervene to prevent higher borrowing costs for businesses and consumers. Yet, policymakers remain reluctant to increase the balance sheet due to inflation concerns. Chair Powell reiterated during the January FOMC press conference that the committee will discuss slowing QT at their March meeting, suggesting that the committee is not ready to stop reducing its balance sheet.

While potential rate cuts and future reductions could increase demand for Treasurys, limited impact on yields is expected due to persistent inflation concerns and lukewarm investor sentiment. Given the continued supply-demand imbalance, we believe short-to-intermediate-term securities offer a more attractive risk-reward profile compared to long-duration bonds due to their lower interest rate sensitivity and potentially higher returns.