Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The Importance of the Federal Reserve’s Inflation Target (May 28, 2024)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

Money has three characteristics: medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account. When money is taught in undergraduate economics classes, these three functions are treated as self-evident, but careful observation suggests that that the first two characteristics are contradictory. If a monetary authority emphasizes the medium of exchange function, then it will tend to oversupply specie to the economy. If the store of value function is favored, then currency is restricted, which tends to support the value of money at the expense of consumption.

In practice, monetary authorities must balance these goals. However, these authorities don’t exercise policy in a vacuum. Instead, the dominating factor usually reflects the power structure of a nation. A society dominated by creditors and asset owners tends to favor the store of value function, whereas one dominated by debtors and consumers favors medium of exchange. Throughout history, monetary authorities have usually either adopted a gold standard, which tends to favor the store of value function, or a fiat standard, which means the currency’s value is set by the central bank’s control of the money supply. Throughout history, a fiat standard tends to favor the medium of exchange function.

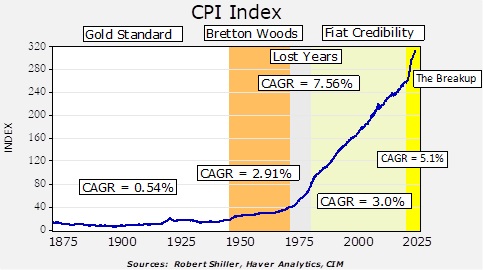

Price levels should reflect which factor the policymakers favor. This chart details the CPI index relative to historical monetary regimes.

Our data series begins in 1871. From the founding of the republic until 1944, the US was on a gold standard for the majority of the time. During wars, the gold standard was usually suspended, but the government tended to return to it once the conflict ended. The gold standard did come under pressure during the Great Depression as the dollar was devalued against gold and US private monetary gold holdings were declared illegal. Despite the erosion, the compound annual growth rate of CPI during this period was 0.54%, clearly low. The gold standard mostly favors capital owners and creditors; a key reason that political support for the gold standard began to erode in the 1920s was due to expanded suffrage. Debtors and the unpropertied that fought during WWI demanded a voice in government after the war ended. What made the gold standard work is that these classes bore the cost of austerity, but once they acquired political power, they were disinclined to accept the austerity demanded by the gold standard.

As WWII was winding down, the allies created a hybrid of the gold standard at Bretton Woods. Currencies were pegged to the dollar and the dollar was pegged to gold. As the chart above shows, it was not as effective as the gold standard in containing inflation, but it worked reasonably well. However, by the early 1970s, a precipitous drain of US gold reserves led President Nixon to suspend gold redemptions in 1971, leading to the “lost years” period on the above chart. Inflation soared.

To contain inflation and restore confidence in currencies under a fiat standard, Western central bankers gradually established two key rules: central bank independence and a clear inflation target. Over time, central banks were freed from their finance ministries, which gave them the power to conduct an independent monetary policy. Since the early 1980s, the central banks of industrialized nations have steadily been granted their independence from fiscal authorities.

The most widely adopted inflation target was 2%; this target was initially established by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand on an offhand comment to a television reporter rather than through careful study. Other central banks soon adopted the standard. Although the Federal Reserve didn’t officially adopt the standard until 2012, it was considered the de facto standard as early as 1996. As the chart above shows, the compound annual growth rate of US CPI over this period exceeded 2%. The general consensus, though, is that an inflation rate between 2% to 3% is low enough to where economic actors don’t factor inflation into consumption and investment decisions. And so, the combination of central bank independence and a clear inflation target has mostly been successful in supporting confidence in fiat currencies. International trade expanded under fiat credibility which suggests that there was general confidence in the dollar as the reserve currency and US Treasurys as the reserve asset.

On the above chart, we have added a fifth regime — The Breakup. Since the pandemic, the pace of inflation has clearly accelerated. Although central bank officials argued that the inflation issue was “transitory,” it has instead proven to be persistent. Central banks have raised interest rates but clearly not to the point where inflation has returned to the Fed’s target level.

There are two factors that we think are undermining the Fiat Credibility regime. First, there is a sentiment among some notable policymakers that the 2% target is too low. The fact that in the last decade central banks in some parts of the world lowered their policy rates below 0% and the FOMC engaged in zero interest rates plus balance sheet expansion is prima fascia evidence that the inflation target is too low. The basic idea is that a higher inflation target would give policymakers greater leeway to stimulate the economy without resorting to unorthodox monetary policy actions.

The second threat may be more formidable. Across the industrialized world, there are rising pressures on fiscal budgets. Aging populations are straining government retirement programs, and rising geopolitical tensions are leading to higher defense spending. In the US, the Congressional Budget Office is projecting high deficits for the rest of the decade.

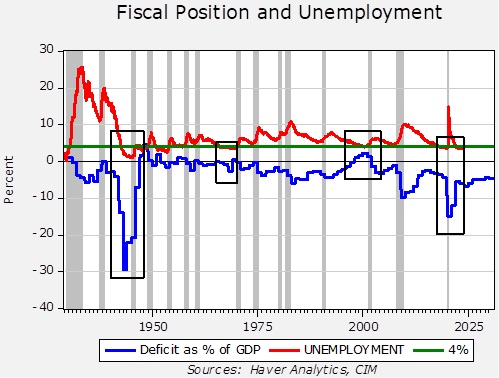

This chart shows the deficit as a percentage of GDP and the unemployment rate. We have inserted boxes around periods where the unemployment rate was at or below 4%. Note that in two periods when the unemployment was at this low level (the late 1960s and late 1990s), deficits tended to be low or, in the case of the latter event, the government ran a surplus. During the other two events (WWII and after the pandemic), the deficit widened while unemployment was low. Usually, a strong economy narrows the deficit as tax receipts rise and spending on welfare support programs declines.

What is concerning about the current situation is that despite low unemployment, the Congressional Budget Office is projecting that rather elevated deficits will be continuing. There is much criticism of this spending in the financial media, with some calling it “the largest deficit in peacetime.” We quibble with this comment, and we disagree about this being “peacetime.” In fact, if this is wartime, the deficits will likely be higher in the future. Defense spending coupled with social spending for retirees will strain budgets. In general, tax increases are politically difficult. At the same time, this cold war we are facing is already fracturing global trade, which will tend to increase structural inflation.

In the face of rising deficits, central bank independence is under threat. These deficits will need to be financed. To prevent sharp increases in interest rates, central banks may be forced to expand their balance sheets to absorb this debt in order to keep interest rates at manageable levels. Obviously, something has to give. We suspect what will “give” will be price levels. The unknown is how households and firms will react to what is essentially an increase in the inflation target. If inflation fears rise enough, economic actors will separate the medium of exchange function of money from the store of value function. If that occurs, some financial and real assets could replace the store of value function for economic actors. Our task, as asset managers, is to determine which assets will gain that function and invest accordingly.