Daily Comment (September 14, 2016)

by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] In the next AAW (published Friday), we will discuss the very important impact of foreign issues on U.S. Treasury yields. This is one reason why the financial markets have become focused on the BOJ’s review of its monetary policy. There are rumors swirling as to what the BOJ is likely to do. According to the most recent reports, the bank looks set to dive deeper into NIRP. When NIRP was deployed in February, market reaction was probably best described as “hostile.” The JPY rallied and the economy showed no signs of improvement. Going lower on NIRP is, in theory, a way to steepen the yield curve. A steeper yield curve is designed to improve the stability of the financial system. Commercial banks are essentially spread traders; they borrow from depositors and lend to debtors. The bank earns money based on the spread. The bank can gain spread in two ways—by taking credit risk or duration risk. Lowering NIRP will widen the spread and support the banks. However, the key concern is disintermediation (disintermediation is the process of taking cash out of the banking system). No major central bank has created conditions where retail depositors have faced negative nominal rates. Commercial depositors have in a few countries, mainly because these depositors have cash holdings that are so large that disintermediation isn’t a real option. However, households just might. If cash flees the banking system, it will make Japan’s economy less efficient.

It is also possible that the BOJ could reduce its QE of longer dated maturities in a bid to raise long-term rates and steepen the yield curve. However, it isn’t clear whether raising long-term rates will hurt the economy by raising borrowing costs. The BOJ might also expand QE but purchase more short-dated paper in a bid to drive down short-term rates and, again, steepen the yield curve.

If longer dated JGB yields continue to rise after the BOJ meets on the 21st, it could have a negative effect on U.S. Treasuries. Perhaps the best sign of success would be a dramatic decline in the JPY. A weaker currency is probably the best policy stimulus Japan can generate. Unfortunately, direct selling of the JPY is frowned upon by the G-7 and G-20 and could invite retaliation. Clearly, QE with the BOJ buying U.S. Treasuries is probably the most effective tool the bank has to stimulate Japan’s economy—fully at the expense of the U.S. economy. The other is probably direct financing of fiscal spending, otherwise known as “helicopter money.”

Finally, a word of caution about the BOJ is in order. Governor Kuroda is a bit of an old school central banker. In the early 1980s, when the economic theory of rational expectations was dominant, the idea was that central bankers could only affect the economy and markets by surprising them. In other words, if a policy move was expected, its impact was mostly discounted by the time the move occurred. The Bundesbank was notorious for “wrong-footing” financial markets with rate changes and currency interventions. Kuroda seems to prefer surprises as well. Thus, it is possible that none of the above discussion occurs and something totally unexpected is announced. This uncertainty is probably a factor in recent market volatility.

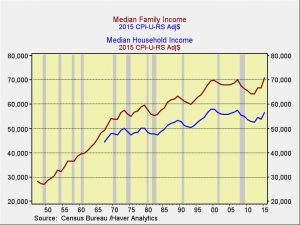

Yesterday, the Census Bureau released its annual calculation of household and family income data. The median showed a strong rise.

This chart shows median family and household incomes adjusted for inflation. The official definition is, “Family income is income of households with two or more persons related through blood, marriage or adoption. Household income is income of family and non-family households.” Both numbers rose sharply last year, with family income up 6.0% and household income up 5.2%.

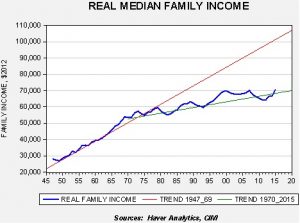

This chart shows real median family income since 1947. We have created two trend lines, the first showing the trend from 1947 into the mid-1970s, and a second from the mid-1970s forward. Note that the slopes are significantly different. Although the current improvement is notable, if real median family income had continued to track the first trend line, median inflation-adjusted family income would be $101,332.30, some $30,635.30 higher than the 2015 report.

A potential issue from this data is also the primary argument from the FOMC’s doves, which is that there is ample labor market slack. Although inflation does remain tame, the rise in both family and household incomes will prompt the hawks to say there is now clear evidence that wages are rising faster and the FOMC needs to lift rates. This is something we will be watching in the coming weeks.

Finally, there were three news items that deserve comment. First, an update to this week’s WGR, Shavkat Mirziyoyev was named acting president of Uzbekistan. Elections will be held on Dec. 4th but will be a formality. Elections are heavily manipulated in Uzbekistan and we are confident that Mirziyoyev will prevail. We expect him to behave much like Karimov except that he may have closer relations with Moscow. Second, a number of progressive groups have warned the Clinton campaign not to consider Lael Brainard for a cabinet post (perhaps Treasury) because of the “Wall Street revolving door.” This strikes us as a bit odd; she seems amenable to left-wing populist causes and may be one of the few people standing in the way of tighter monetary policy. If the standard from left-wing populists is that no one with financial industry experience can work for the president, about the only people who will qualify will be academics. It almost seems that experience has become a disqualifier for populists on either wing. Third, Bloomberg polls show Trump leading in Ohio by five points. This is a rather big swing and shows that Sen. Clinton’s bad week has had an impact on the polls. If Trump starts polling stronger, we may see a negative market reaction, especially in equities.