Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The Price of Central Bank Independence (July 29, 2024)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

Despite the formal separation of the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department in 1951, the two bodies continued to collaborate closely on economic policy for nearly two decades. The coordination aimed to improve the effectiveness of initiatives like stimulating economic growth or preventing the overheating of the economy. While this balancing act worked well under Bretton Woods, the system’s collapse in the 1970s strained the relationship between the two institutions.

The end of the gold-dollar exchange system in the early 1970s left the United States struggling to maintain confidence in its currency. Foreign leaders, like Charles de Gaulle of France, had previously been critical of America’s inability to control spending and argued that it devalued the dollar held by other countries. This anxiety surrounding the dollar likely played a role in Saudi Arabia’s decision to hike oil prices and impose an oil embargo on the US in response to its involvement in the Arab-Israeli War. This move significantly contributed to a surge in US inflation.

To address this, President Jimmy Carter delivered his now-famous “malaise” speech and requested resignations from his White House staff and cabinet. As part of this reshuffle, he appointed Paul Volcker as Fed Chair. This decision, though, cost him his presidency and established a precedent for the Fed to prioritize its monetary policy goals, even if they diverged from fiscal policy during economic expansions.

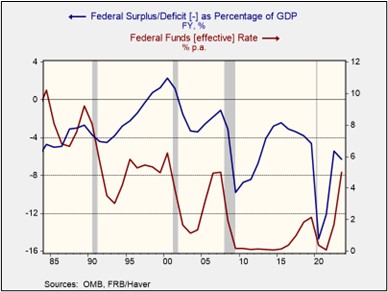

Investors tend to favor policies that nurture economic growth while also keeping inflation in check. This balancing act can be tricky, but the Federal Reserve’s approach exemplifies how it’s done. As the chart below shows, the Fed typically lowers interest rates during recessions to jumpstart the economy. Conversely, during economic booms, it usually tightens policy to slow borrowing and spending, keep the economy from overheating, and prevent inflation. This strategy resonates with investors because it ensures that they’re compensated for potential inflation and the risks associated with rising government debt.

However, what benefits financial markets doesn’t always translate to political popularity. Lawmakers, especially populists, have clashed with the Fed when its actions run counter to their agendas. Former President Donald Trump frequently lambasted the Fed for raising rates while he was working to stimulate economic growth through lower tax rates. Meanwhile, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren has accused the central bank of raising interest rates to the detriment of its inflation target, suggesting that its hiking cycle contributed to rising shelter and insurance prices.

Rising debt has further strained the relationship between the central bank and lawmakers. The gross federal debt as a percentage of GDP rose from 100.5% in 2019 to 126.4% in 2020. While some progress has been made in reducing the debt, Fed officials have warned that the government should do more to rein in its spending to prevent a rising debt problem. The Congressional Budget Office projects that weaker economic growth and higher interest rates could push the debt to 140% of GDP by 2034.

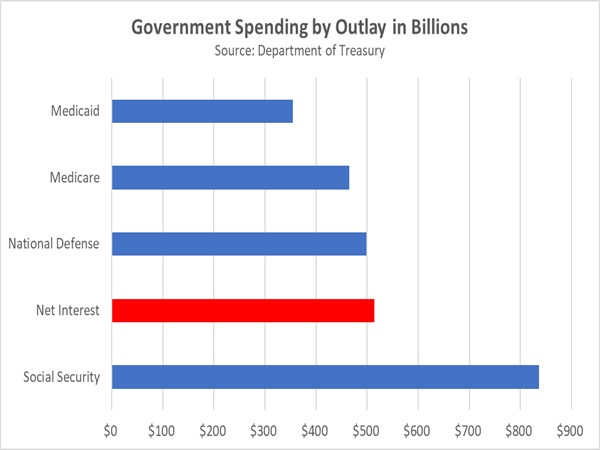

The government’s recent shift toward issuing more short-term bills exposes it to greater interest rate fluctuations, further complicating the Fed’s ability to shield itself from scrutiny. According to one estimate, the government issued 70% of its Treasury debt in bills this year. This means future rate hikes by the Fed could significantly increase the government’s borrowing costs. Highlighting the urgency of the issue, the cost of servicing the debt (net interest) has surpassed military spending in the first seven months of fiscal year 2024, as shown in the chart below.

The rising tensions between the Fed and the government have likely fueled concerns about the effectiveness of their independent roles, prompting some to question whether the Fed and the government should return to their pre-Volcker relationship. Some lawmakers have pushed for the executive branch to have more say in future monetary policy. The new framework would require central bankers to consult with the president on interest rate decisions and grant him the authority to dismiss the central bank head if he disapproves.

A weakened central bank could lose its ability to act as a critical check on excessive government spending. This scenario raises concerns for bondholders, who could face the brunt of rising inflation if fiscal spending spirals out of control. Further compounding the uncertainty, foreign entities may be hesitant to hold US dollars due to a perceived lack of clear policy direction. This could lead them to diversify their reserves, seeking assets like gold that might offer a more stable store of value.

Despite no direct challenges to Fed independence from the current presidential candidates, anxieties linger about potential meddling. This could dampen investor enthusiasm for US financial assets and exacerbate market volatility as the election nears. However, a silver lining exists for some. International companies and US companies with foreign currency exposure could benefit from a potentially weaker dollar, translating to higher returns.