Asset Allocation Weekly (December 9, 2016)

by Asset Allocation Committee

The rapid rise in longer duration Treasury yields since the presidential election has been surprising. As of December 8, the 10-year T-note yield was approximately 2.40%. Although President-elect Trump’s policies will probably be inflationary, it is still unclear how much of his arguably vague plans will get passed. It is possible the FOMC will become more hawkish and we have seen some increase in rate hike expectations.[1] Still, our 10-year T-note model is putting the fair value yield at 1.85%. Assuming fed funds at 1.25% still only raises the 10-year rate to 2.20%. Taking oil to $60 and assuming the 1.25% fed funds only raises the fair value yield to 2.27%. Only when assuming steady oil, fed funds at 1.25% and German bunds at 1.25% (up from the current 33 bps) does the yield even reach 2.40%. The current spike in yields can be best justified by assuming a significant jump in inflation expectations.

In our yield model we use the 15-year average of CPI as a proxy for inflation expectations. This assumption comes from the work of Milton Friedman, who postulated that inflation expectations are derived over a long-term time frame. We realize our calculation is a proxy but have refrained from using more market-based expectations because of their lack of predictability. If one assumes that nominal rates are the sum of the expectations of real rates plus inflation forecasts, inflation forecasts are very important to predicting nominal interest rates.

If the lifetime experience of inflation is important, then what is the most important age? We estimate that 60 is a reasonable age; the average age of the Senate is 61 years, the current FOMC average is 62 and the average age of an S&P 500 CEO is 57.[2] Simply put, it’s around the age of 60 that people come into power in politics and business. We believe that their personal experiences color the expectations of any investor and so using 60 as an influential age makes sense.

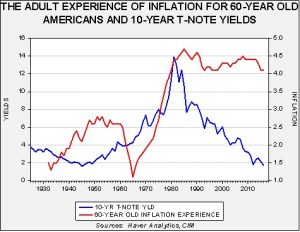

This chart shows the adult experience of inflation for a person turning 60 from 1932 to the present. To reflect the adult experience, we use the average annual change in CPI from ages 16 to 60. Note that inflation experience rose into the late 1940s and stabilized into 1960, when it fell sharply. This was the generation that entered adulthood during the Great Depression. It is interesting to note that as rates began to rise in the mid-1960s, the inflation experience steadily rose as well. Essentially, the rise in rates coincided with the rise in inflation experience. However, after peaking in 1981, bond yields began a steady drop into the current year despite the relatively high level of inflation experience. On the other hand, T-note yields exceeded the inflation experience of 60-year-olds in absolute terms until 2002.

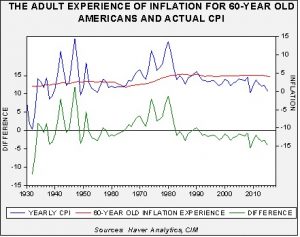

This chart shows the actual inflation rate compared to an average 60-year-old’s adult experience of inflation. In general, bull markets in bonds tend to occur when the actual inflation rate is persistently below the average rate. Bear markets happen when the opposite condition is in place. Currently, the actual inflation rate is still well below the average rate, suggesting that the bull market in bonds should have more time to run. However, our worry is that the average 60-year-old is unusually sensitive to inflation fears and thus may overreact to the incoming president’s policies. In other words, inflation expectations may become unanchored rather quickly, forcing the Federal Reserve to turn unexpectedly hawkish. Thus, we are taking a more cautious stance on fixed income into 2017, expecting higher yields and greater duration risk. At the same time, we will be closely monitoring the economy in light of less accommodative monetary policy. Most recessions occur because the Fed tightens too much. We don’t expect that to become a problem until late next year or early 2018 if the Fed continues to raise rates. So, for the upcoming year, we expect a weak fixed income environment.

_______________________

[1] For example, the two-year deferred Eurodollar futures, which measure three-month LIBOR two years into the future, have jumped nearly 50 bps since the election.