Daily Comment (December 14, 2016)

by Bill O’Grady, Kaisa Stucke, and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EST] It’s FOMC day! The statement comes out at 2:00 EST with the press conference a half hour later. We will also get new forecasts and a refreshed “dots” plot. Market expectations call for a “dovish tightening,” where the FOMC raises rates by 25 bps and signals 50 bps, at most, for next year. We don’t expect any comments about fiscal policy in the statement. Chair Yellen will almost certainly get asked about this during the press conference and her most likely response will be that the FOMC will adjust to whatever effects fiscal policy has on the economy and make it clear that the central bank won’t preempt any fiscal changes.

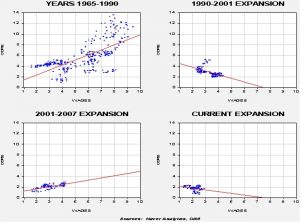

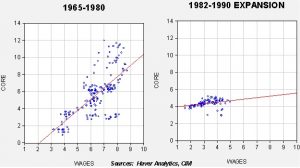

These four charts show one of the key problems the FOMC faces. The chart in the upper left shows the relationship between yearly wage increases for non-supervisory workers and core CPI from 1965 to 1990 (all four charts are scaled to this particular one). This is the period when all of the current members of the FOMC completed their educations. The linear relationship is clear; rising wages coincide with rising inflation. The best fit line suggests that 4% wage growth leads to inflation just above 4%. The other three charts show the behavior of these variables over the past three recoveries. In two of the recoveries, the relationship is actually inverse; rising wages coincide with weaker inflation. In the 2001-07 expansion, the relationship fits the theory of the Phillips Curve but the slope has clearly flattened; 4% wages barely bring inflation higher than 2%. What has changed? Why did the Phillips Curve relationship seem to exist before the 1990s change? We believe globalization and deregulation changed the nature of the relationship between wages and inflation, essentially breaking the link. And so, in line with this position, the Phillips Curve relationship began breaking down by the 1980s.

By the Reagan years, the Phillips curve had mostly flattened. If rising wages are the independent variable in the relationship between wages and prices (as suggested by the Phillips Curve), then it hasn’t really been operative since 1980. Still, the Phillips Curve remains one of the primary factors in the Fed’s view of monetary policy. The bottom line here is that there isn’t much urgency for the FOMC to raise rates and thus we suspect they will continue to move slowly, which will be supportive for the economy and risk assets.