Asset Allocation Weekly (March 24, 2017)

by Asset Allocation Committee

In a recent Bloomberg Surveillance podcast,[1] Sebastian Mallaby made an interesting observation about the recent Fed tightening. He noted how the asset markets mostly ignored or cheered the move. Mallaby suggested that this isn’t necessarily a good outcome, meaning that central bank tightening should not be welcomed by the financial markets. When it is, it can make the markets complacent; this is one of the main tenets of Hyman Minsky’s research.

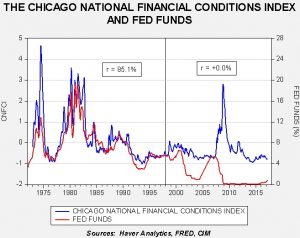

This chart clearly shows how financial markets have changed.

The blue line on the chart shows the Chicago FRB Financial Conditions Index. It measures the level of stress in the financial system. It is constructed of 105 variables, including the level of interest rates, credit spreads, equity and debt market volatility, delinquencies, borrower and lender surveys, debt and equity issuance, debt levels, equity levels and various commodity prices (including gold). A rising line indicates increasing financial stress. The red line is the effective fed funds rate. Until 1998, the two series were positively and closely correlated. When the Fed raised rates, financial stress rose; when the Fed lowered rates, stress declined.

We believe one factor that changed this relationship is policy transparency. Starting in the late 1980s, the Fed became increasingly transparent. Before 1988, for example, the FOMC would meet but issue no statement about what it had decided to do. Investors and the financial system had to guess if policy had been changed. Starting in 1988, the central bank began publishing its target rate. In the 1990s, it began issuing a statement when rates changed; eventually, a statement followed all meetings. As the FOMC has become more transparent, the correlation between stress and the level of fed funds has changed. Essentially, the markets now know with a high degree of certainty when rate changes are likely. This is especially true of tightening. The FOMC appears to avoid making rate hikes that surprise the market.

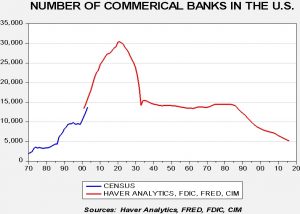

Central bank policy goals are another factor that may have changed the stress/fed funds relationship. Although Congress has specifically tasked the Fed with managing full employment and low inflation, all central banks exist to act as lenders of last resort. Central banks provide liquidity during panics to prevent widespread financial firm failures during crises. For most of the post-Depression period, the financial system was heavily regulated; investment banking and commercial banking were separated by Glass-Steagall, and the Bank Holding Company Act restrained bank operations across state lines. This led to a high number of small commercial banks.

This chart shows the number of commercial banks in the U.S. There is a break in the series around 1905; we have put together a time series from a variety of sources. There was a sharp consolidation of banks during the 1920s into the early years of the Depression. Banking regulation kept the number mostly stable. Financial institution failures show how the financial system stabilized from the mid-1930s into the early 1980s.

Financial firm failures began to rise during WWI and spiked during the Great Depression. The regulatory environment focused on stability until the 1980s, when deregulation began. The goal of deregulation was to improve the efficiency of the banking system. Although it did improve efficiency, it also made it more fragile. The rise in failures in the 1980s was due to the S&L Crisis, while the recent rise was due to the Great Financial Crisis.

From the mid-1930s into the early 1980s, the Federal Reserve did not have to concern itself with financial stability. In a world of widely distributed, heavily regulated commercial and investment banks, the odds of failure were low and the impact from any particular failure was insignificant. Thus, monetary policy could be conducted simply to manage the goals of controlled inflation and full employment. However, in the current deregulated environment, the Fed now has to be concerned with financial system stability. This is why we believe the central bank has opted to become more transparent. The problem is, that by adopting this policy, the central bank has lost control over financial stress. The data indicates that when the FOMC raises rates, financial stress tends to remain stable…until some sort of crisis occurs. And, perversely, easing policy seems to have little effect on reducing stress.

Instead, what seems to happen is that monetary policy, by being transparent and designed not to increase financial stress, leads to overconfident investors who tend to build asset prices to unsustainable levels. This leads to eventual asset price corrections and easier monetary policy. Following Hyman Minsky’s theory, low financial stress becomes the catalyst for rising asset prices that eventually become problematic; unfortunately, the usual response of easing monetary policy does little to reduce financial stress.

What does this mean for investors? Sadly, it means that monetary policy seems designed to maintain low levels of financial stress and tends to lift asset prices to the point of unsustainability, which then leads to painful corrections. This isn’t the only factor involved; this same monetary policy tends to foster long economic expansions which also support asset prices. Although each investor’s goals and risk tolerance is different, this analysis suggests that risks are higher than they first appear and balanced portfolios are one of the better longer term responses to this condition.

________________________________

[1] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/audio/2017-03-16/trump-s-budget-is-borderline-incompetent-furman-says