Asset Allocation Weekly (June 15, 2018)

by Asset Allocation Committee

The last topic in our series on secular trends is the dollar. It is arguable as to whether or not exchange rates are actually an asset class. In our asset allocation, we don’t treat it as one. On the other hand, the behavior of the dollar affects most of the other asset classes. There is a clear inverse correlation between the dollar and commodities. Since most commodities are priced in dollars, a weaker dollar is a price cut for non-dollar buyers. The increase in demand will usually lead to higher prices for commodities when the dollar dips. Foreign equities to U.S. investors are directly affected by the dollar’s exchange value. In general, foreign equities tend to outperform during periods of dollar weakness because, for a dollar-domiciled investor, appreciating foreign currencies act as a tailwind for foreign assets. Of course, if foreign currencies become too strong, it adversely affects the foreign economy and can become too much of a good thing. Even domestic equities are affected. A weaker dollar tends to support large cap stocks relative to small caps because the latter are less globalized. And, an excessively weak dollar can foster tighter monetary policy as a very strong dollar can prompt the Federal Reserve to ease credit.

The dollar is the nexus of most foreign exchange transactions. Although there is a market for cross rates in the major currencies, most transactions are into and out of dollars. That way dealers don’t have to make markets in thousands of currency permutations. Because of the widespread use of the U.S. dollar, it is the global reserve currency; when nations accumulate foreign reserves, the currency of choice is mostly the greenback. About 63% of official foreign reserves are in dollars, with the next closest competitor, the euro, at 20%.[1] The dollar represents 88% of all forex turnover.[2] Thus, the dollar’s exchange rate against various currencies deviates from classic textbook valuation measures because there is a natural demand for transaction and reserve purposes.

However, even with that caveat, some opinion on the direction of the dollar is critical because, as noted above, it affects numerous markets. In our observation, the dollar’s path tends to be driven by “flavor of the month” factors. During various periods, markets focus on the trade deficit, relative productivity, interest rate differentials and monetary policy divergences, to name a few. In other words, there hasn’t be a consistent variable that has affected the dollar’s exchange rate in all markets. Here are the variables we use when examining the greenback.

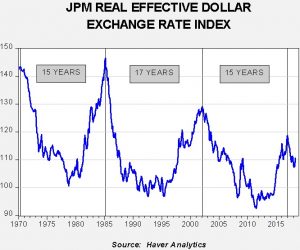

First, history shows a cycle to the dollar.

To measure the general value of the dollar, we use the JP Morgan real effective dollar index, which adjusts the dollar for relative inflation and trade. We note that the dollar tends to peak about every 15 to 17 years. There is always a danger in such observations…it’s a bit of the correlation/causality problem. Just because something has followed a pattern for a long time doesn’t mean it will do so in the future. This cycle does “rhyme” with relative growth; the dollar tends to strengthen when U.S. economic growth exceeds the rest of the world. However, the important market takeaway from this chart for long-term investors is that exchange rates probably don’t matter if one holds a position for around 15 years. And, dollar bear markets tend to last longer than dollar bull markets.

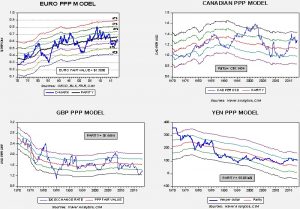

Second, for long-term valuation purposes, we use purchasing power parity. This theory of currency valuation argues that exchange rates should adjust to equalize prices across countries. A nation with higher price levels should have a weaker currency, which would equalize the prices of a lower inflation country.

This chart shows the calculation of parity for four currencies, the euro, yen, Canadian dollar and British pound. Deviations from the model’s fair value forecast are wide but, at extremes, the model does suggest reversals are more likely. Currently, the dollar is richly valued compared to these four currencies.

What about other models? Relative growth between Europe and the U.S. yields a similar fair value. Interest rate differentials clearly favor the greenback but the relationship isn’t all that strong either.

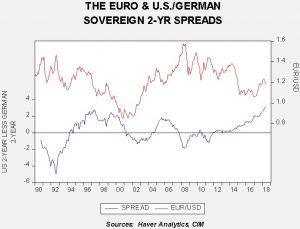

This chart shows the spread between U.S. and German two-year sovereigns and the EUR/USD exchange rate. Although the rate spread is historically wide, in the last tightening cycle in 2004-06 the dollar faded shortly after the tightening cycle ended.

Perhaps the most important issue facing the dollar is the future of American hegemony. If the world loses faith in the dollar’s reserve value, we would expect a profound bear market to develop. At this point, there is no obvious rival to the dollar. However, one of the reasons no rival exists is that no other nation with a reasonably attractive currency is willing to run persistent trade deficits. The Trump administration is trying to adjust or reverse America’s importer of last resort role which is part of being the reserve currency provider. If the U.S. puts up trade barriers, we would expect the dollar to appreciate as long as reserve demand remains. But, if the world decides the U.S. is no longer a reliable provider of the reserve currency, even if no obvious replacement exists, the dollar will almost certainly decline. Reserve currency changes don’t occur very often; we have only had two reserve currencies over the past two centuries, the British pound from 1815 to 1920 and the U.S. dollar from 1920 to the present. With events that occur so rarely, it is difficult to determine the path of the greenback but it does appear we are moving into an era of significant change. This is a factor we will be closely monitoring in the coming months and years.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reserve_currency