Daily Comment (October 2, 2018)

by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] We are seeing a bit of weakness this morning, mostly due to comments coming out of Italy. Here is what we are watching:

Italy: The head of the finance committee in the lower house of Italy’s legislature, Claudio Borghi, was quoted as saying that Italy would not have a debt problem if it weren’t part of the Eurozone.[1] Although his comments are imprudent, they are mostly true. Outside the Eurozone, Italy would have higher interest rates but would likely have depreciated its exchange rate against the dollar and euro in a bid to keep Italy’s economy competitive. There would be no government solvency crisis because it could print its own debt service instrument. Although there is much handwringing about the Italian budget and fears of the populist government that heads the country, the real problem is that the euro project was faulty at its onset. A nation loses some of its sovereignty when it loses control of its currency.

It has been our position that a point will be reached where the euro project fails and nations exit the single currency. This is because the Eurozone, as it currently operates, allows Germany to dominate the single currency bloc. This setup is becoming increasingly unacceptable to some nations within the Eurozone, especially along the southern tier. We would not be surprised to see two currency blocs emerge, a northern and a southern euro. The problem nation in this configuration is France; economically, it should be in the southern euro, but, politically, it will want to be in the northern euro.

For the time being, Italy will remain a tension point in Europe. If the Eurozone cannot accommodate its goal of expanded fiscal spending and faster growth, it could trigger a crisis similar to the Greek problem. However, given Italy’s size, the Italian problem will threaten the structural integrity of the Eurozone. In the near term, we think Germany will eventually allow Italy to overspend. However, that outcome won’t be permitted indefinitely.

Powell speaks: As noted below, Chair Powell will give a talk this afternoon. The WSJ[2] points out this morning that the Powell Fed is becoming increasingly parsimonious in its forward guidance. This trend is, in our opinion, a favorable one. Our research has shown that increasing transparency has weakened the relationship between fed funds and financial stability.

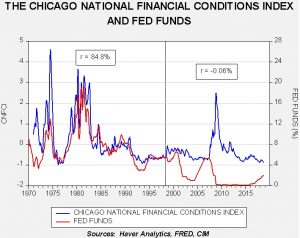

This chart shows the relationship between fed funds and the Chicago FRB National Financial Conditions Index (NFCI). The NFCI is a measure of financial stress; the higher the reading, the higher the level of financial stress. From 1973 to mid-1998, the two series were highly and positively correlated; the higher the level of fed funds, the more financial conditions deteriorated. Thus, as the FOMC raised rates, financial conditions deteriorated, leading to weaker economic activity. When the FOMC lowered rates, financial stress would dissipate, boosting growth. Financial stress became, in effect, a force multiplier for monetary policy.

Since mid-1998, the two series have become increasingly uncorrelated. We believe this is due to increased Fed transparency. As the FOMC became more open in publicizing its policy goals, financial markets could anticipate policy changes. This reduced financial stress, which is probably seen as a good thing (we are not so convinced), but it also removed stress as a policy force multiplier. Thus, in the mid-aughts, the Fed raised rates without a commensurate rise in stress. This lack of stress was part of the “Greenspan conundrum” – the Fed was raising rates but long rates and borrowing did not respond as expected. Then, when the financial crisis hit in 2008, the FOMC aggressively cut rates to no avail; stress rose significantly and it took years of ZIRP before stress levels fell to pre-crisis levels.

Thus, Powell’s shift to a “less is more” approach should be lauded. Although financial stress is usually unwelcome, it should be noted that financial stress injects caution into the minds of investors and can act, in part, to prevent excessive enthusiasm.

Another factor that seems to be developing is that allegiance to the Phillips Curve may be waning as the FOMC ages. At present, there is no other model to replace it. In the absence of a new working model, policymakers appear to be taking a wait-and-see approach. At present, we suspect the term “market signals” is all about the yield curve and a growing majority on the FOMC may take a cautious approach and vote to pause the rate hike cycle as we approach inversion. We will be looking for any hints of such ideas in Powell’s comments today.

[1] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-italy-budget-dimaio/italy-wont-change-2-4-percent-deficit-goal-despite-eu-pressure-di-maio-idUSKCN1MC0MD

[2] https://www.wsj.com/articles/fed-looks-to-pare-language-describing-future-of-rates-policy-1538472600