Asset Allocation Weekly (December 23, 2016)

by Asset Allocation Committee

Due to the upcoming holidays, the next edition of this report will be published on January 6, 2017.

The Fed gave us a modest hawkish surprise last week, calling for three rate hikes in 2017 rather than two. The news has boosted Treasury yields and lifted the dollar. Equities mostly absorbed the news without incident.

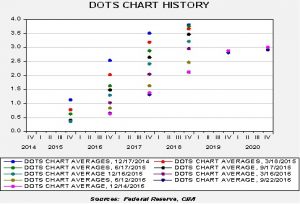

Here is a chart of the FOMC’s average dots over the past two years.

The fuchsia dots represent the most recent meeting. The dots have stopped their steady progression toward lower levels. For better or worse, the path of policy expectations from the dots suggests that the FOMC is becoming comfortable with this path of hikes.

Here is the dots plot from September.

Note the purple line, which is the LIBOR-OIS curve from the meeting day. It has jumped from where it was on the meeting date in September, shown by the red line. For the past few years, the FOMC dots have tended to decline toward the market. The rise in the LIBOR-OIS curve suggests that process is reversing.

This is the new dots plot, released at the December meeting.

For 2017, the median forecast is currently 1.375%, up from 1.125% in September. For 2018, the median is up to 2.125% from 1.875%. Two participants see no change next year but one of those is probably St. Louis FRB President Bullard, who has decided not to participate in the dots procedure. Although market expectations continue to lag, we did see the LIBOR-OIS rate rise to 1.25% from 0.875% in September.

This can be seen in the deferred Eurodollar futures.

The jump in yields since Trump’s election has been striking. We are approaching the highest level of implied rates since the “taper tantrum.” This rise triggered the onset of the dollar rally in mid-2014 and we note that the dollar has been rising since the election.

To get some sense of where policy is in relation to the neutral rate, we use the Mankiw rule model, incorporating the recent rate changes by the FOMC. This model attempts to determine the neutral rate for fed funds, which is a rate that is neither accommodative nor stimulative. Mankiw’s model is a variation of the Taylor Rule. The latter measures the neutral rate using core CPI and the difference between GDP and potential GDP, which is an estimate of slack in the economy. Potential GDP cannot be directly observed, only estimated. To overcome this problem, Mankiw used the unemployment rate as a proxy for economic slack. We have created four versions of the rule, one that follows the original construction by using the unemployment rate as a measure of slack, a second that uses the employment/population ratio, a third using involuntary part-time workers as a percentage of the total labor force and a fourth using yearly wage growth for non-supervisory workers.

Using the unemployment rate, the neutral rate is now 3.63%. Using the employment/population ratio, the neutral rate is 1.08%. Using involuntary part-time employment, the neutral rate is 2.79%. And finally, the wage growth model puts the neutral rate at 1.56%.

It is still uncertain which of these variants best reflects slack (or lack thereof) in the economy. Although we tend to think that wage growth or the employment/population ratio is the best measure of slack, the key is which one policymakers view as the most consistent with measuring slack. At this point, we don’t know, although we think the hawks are probably relying on the unemployment rate variant while the chair and most of the doves probably believe the involuntary part-time employment variant is the best measure. The involuntary part-time employment variant is most consistent with six rate hikes over the next 24 months. That path would bring the policy rate near neutral; however, if they are wrong and, for example, the employment/population ratio is actually correct, then policy will be overly restrictive (assuming that ratio doesn’t improve dramatically). Thus, the FOMC is moving rates higher in a slow fashion to allow them time to adjust if it turns out there is more slack (reflected by the lower neutral rate variants) than some data would suggest. Of course, by going slow, assuming the higher neutral rate variants are correct, the Fed could keep policy overly accommodative longer than it should. However, as long as the economy remains globalized and deregulated enough to allow for the nearly unfettered introduction of new technology, being late isn’t all that risky. That assumption would change if the incoming President Trump puts up trade barriers. Thus, the path of monetary policy could be a risk factor in the upcoming year.