Asset Allocation Weekly (January 19, 2018)

by Asset Allocation Committee

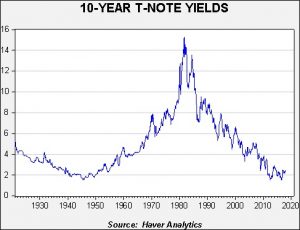

Since the beginning of the year, long-term interest rates have moved higher. The constant maturity 10-year Treasury yield ended 2017 at 2.40%. That yield climbed to 2.60% in January, which is above our recently released 2018 Outlook forecast. We are not adjusting our forecast quite yet because the driving factor behind our forecast was continued flattening of the yield curve. However, if the curve doesn’t flatten further, we will need to revisit that forecast.

The recent rise in yields has led several commentators to declare a new bear market in bonds had developed. We sort of agree with this statement; we believe a secular bear market in bonds began in 2016 and we will likely see gradually rising rates for the foreseeable future. However, the key word is “gradually.” The last secular bear market in bonds began in 1945 and took over two decades to become a serious problem for financial markets.

The above chart shows the 10-year T-note yield from 1921 to the present. In 1945, yields made their secular low and gradually rose into the early 1980s. Note the gradual ascent of yields for the first couple decades. It wasn’t until yields rose above 5% in the late 1960s that rising rates began to have an adverse impact on financial markets. Of course, when one is talking about secular cycles that last three to four decades, the last experience may not be indicative of what the current secular bear market will look like. Fortunately, the Bank of England has maintained long-term databases of British interest rates and can offer us some insights into long-term cycles. The chart below shows the interest rate of British Consols beginning in 1701. These instruments were bonds without a maturity; essentially, they were very long-duration instruments. Note that bull and bear markets tended to last a very long time and, in fact, the British bond bear market after WWII was impressive in terms of rate increases but rather normal in terms of length.

Why do secular cycles in bonds last so long? For the most part, secular cycles in long-duration interest rates are driven by inflation expectations. Rising inflation undermines the real value of interest return; investors, stung by inflation, will demand ever higher yields for protection. When policy changes to corral inflation, it takes some time before investors “forget” their unpleasant experiences and accept a lower interest rate. After a long period of low inflation, investors are “fooled” by rising inflation, at least at its early stages. This underestimation in inflation leads to falling real returns and prompts demand for rising rates.

What makes the current period interesting is that the baby boomers are unusually sensitive to inflation fears because most of them spent their formative years during the high-inflation period of the 1970s. Thus, any signs of inflation, regardless of how minor, tend to lead to “discomfort” in the fixed income markets. The existence and current prominence of the baby boom generation will likely keep long-duration rates from rising very much in the coming years. The oldest boomer is 72 this year, while the youngest is 54. Clearly, over the next two decades, the memory of 1970s inflation will fade and the subsequent generations will be much more likely to be fooled by inflation and will be slow to demand higher yields. This fact will probably lead to the final stages of the bond bear market, which will be rather painful for investors.

So, what does an investor do in the meantime? We look for gradually rising rates over time. The policies of neoliberalism, which supported globalization and deregulation,[1] successfully ended the high inflation period of the 1970s. We are likely in the early stages of a retreat from neoliberalism. The rise of populism in the West is partly due to citizens becoming acutely aware of the costs of neoliberalism (high level of inequality and job insecurity) without being aware of its benefits (low inflation, long business expansions). Although it will take some time, tolerance of higher inflation will likely increase. Investors have two strategies for such an environment. First, corporate credit tends to do better in the early stages of a secular bear market because gradually rising prices reduce credit risk as firms find it easier to pass along higher prices. Second, bond laddering, the purchase of instruments at various points of the yield curve, offers some defense from rising rates. As time passes, the duration of a laddered portfolio falls, reducing rate risk. As the nearest instrument matures, the investor buys a longer term instrument and the process repeats. We are currently deploying both strategies in our fixed income allocations.

[1] We define deregulation as the unfettered implementation of new technology and methods on the economy.