Asset Allocation Weekly (May 10, 2019)

by Asset Allocation Committee

While the financial industry is rife with performance comparisons to selected benchmarks, the most important investing goal for the majority of clients is a return above inflation that avoids catastrophic losses. Although beating the S&P 500 is a nice goal, solely focusing on that outcome may lead an investor to accept more risk than appropriate. This is an age-old issue where one confuses ends with means. Benchmarking is a means to an end. A benchmark gives investors some insight into how their investments are doing but should never be considered an end in itself. Sadly, measurement of performance seems to have eclipsed, and even replaced, the principal goals for clients. In other words, the benchmark has become the goal.

A good example of the problem with benchmarking is found in academia. Students have been told that the “4.0” is the clear marker of academic success. Now, getting all “As” is a good thing. But, anyone who has been to college knows that the GPA can be gamed. Students can fill their electives with easy courses. They can select the easiest professors in their major’s hardest courses. And, they can cheat. Or, perhaps equally as perverse, they can “know it for the test.” In other words, they can memorize the necessary information but fail to really understand it. Resolving this issue is part of hiring new graduates. There are ways to ferret out who knows their stuff and who gamed. Checking transcripts is a good way to look for clues—what were the electives and how did the candidate do in the hard classes? Another is to ask questions about the most basic components of a discipline but in a way that is rarely presented in class. An example for economists is, “Assume all drug users are addicts; what is the best way to reduce illicit drug consumption?”[1] However, how many positions are filled by candidates who are screened by GPA? In other words, how many good candidates never get an interview because their GPA fell below 3.5 because they took more challenging course work?

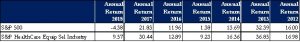

Let’s suppose that instead of attempting to help clients accumulate wealth within their acceptable risk tolerance, the goal was to outperform the S&P 500 Index and the criteria was what outperformed the index over the past seven calendar years. Out of the 34,468 U.S. dollar-based indices in Morningstar’s database, the sole index that met this criteria was the S&P HealthCare Equipment Select Industry Index. Naturally, exposure exclusively to this single index would be a poor investment strategy for the vast majority of clients, as it would expose them to very specific risks, yet it underscores the notion that simply striving to outperform the return of a particular index is fraught with the potential risk of a permanent impairment of capital.

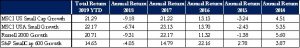

Another problem that arises in making relative performance the principal objective is the potential for miscreants to juggle benchmarks in order to appear successful. As an example, the table below illustrates the divergence that is associated with popular small cap growth benchmarks. While all four of the benchmarks in the table are from highly reputable providers with well-documented methodologies for the U.S. small cap growth stocks included in their indices, the variance among these four in any given year can be profound. Note that even with indices from the same vendor the differences can be significant as evidenced by the MSCI U.S. Small Cap Growth Index varying from the MSCI U.S.A. Small Growth by 244 basis points in 2018.

A further complication that may be encountered is the utilization of benchmarks that incorporate significant complexity in the myriad sub-asset classes that roll up to major asset classes. The resulting information will be a hash of statistics that are of little use to either investors or advisor supervision.

These potential pitfalls do not obviate the necessity of monitoring and evaluating relative performance as part of proper due diligence. The evaluation of a manager’s portfolio or asset allocation strategy against an appropriate benchmark is an essential tool for validation of an investment thesis, which can lead to the achievement of the client’s goals. However, this can be taken to extremes. Our industry’s all-consuming fascination with performance measurement has the potential to cause actions that are perpendicular to the goal of inflation-adjusted wealth creation, such as performance chasing.

What, then, is the correct approach to ensure a manager is properly positioned in a client’s portfolio or an asset allocation strategy is appropriate to help attain the client’s goal? The most straightforward means is to evaluate a manager or asset allocation strategy against a benchmark that is objective, possesses a sound methodology, recognizable, germane to the asset class represented and free of unnecessary complexity. For this last facet, the notion of Occam’s razor applies. This approach will naturally yield significant tracking error; however, tracking error should not only be expected, but embraced, for an active manager. While on a quarter-to-quarter basis investors may observe divergent returns relative to the benchmark, during discrete, representative periods and especially through a full market cycle, an uncomplicated and recognizable benchmark will represent a solid barometer against which to measure the risk-adjusted return of a manager or investment strategy. This will serve to evaluate whether the manager or strategy is contributing to the overarching client goal. But, ultimately, the key point to remember is that a benchmark is a means to an end, not an end in itself.

[1] If all users are addicts, then the demand curve is highly inelastic. Reducing supply merely drives up the price, but reducing demand (drug rehab, substitution) could reduce demand and have the biggest effect on reducing consumption.