Asset Allocation Weekly – The Prices We Don’t See (October 1, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

For four consecutive months, consumer prices as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have risen 5% from the prior year. The pace of inflation has sparked concerns that the Federal Reserve may be wrong in describing inflation as being transitory. However, our research suggests there may be more validity to the Fed’s claim than meets the eye. In this report, we discuss some evidence supporting the argument that inflation will be transitory. We also discuss the possibility that inflation may last longer than expected as well as the length of time in which we expect inflation to normalize.

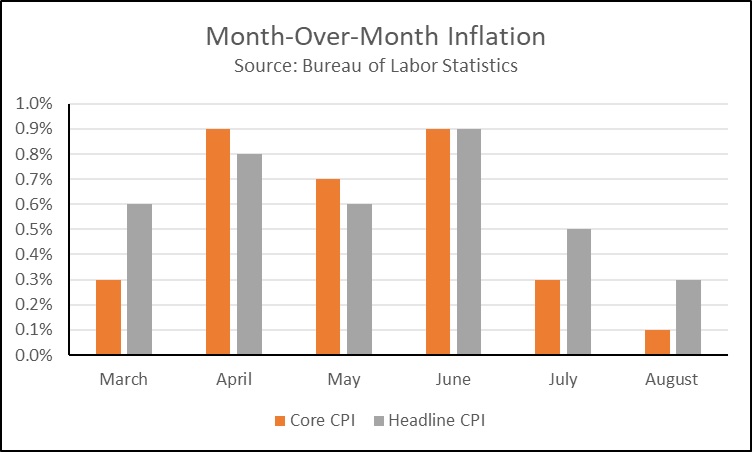

The most recent CPI report showed that inflationary pressures have eased sharply over the last two months. Monthly inflation (which is more sensitive to incremental change compared to annual comparisons) as measured by the CPI excluding the volatile food and energy components (Core CPI) went from a 30-year high in April to benign levels in August. The reduction in inflationary pressures coincided with a steep deceleration in the month-to-month inflation of used cars and trucks. In August, used car and truck prices fell 1.5% from the prior month. The decline in used car and truck prices likely relieved much of the pressure on the overall price index.

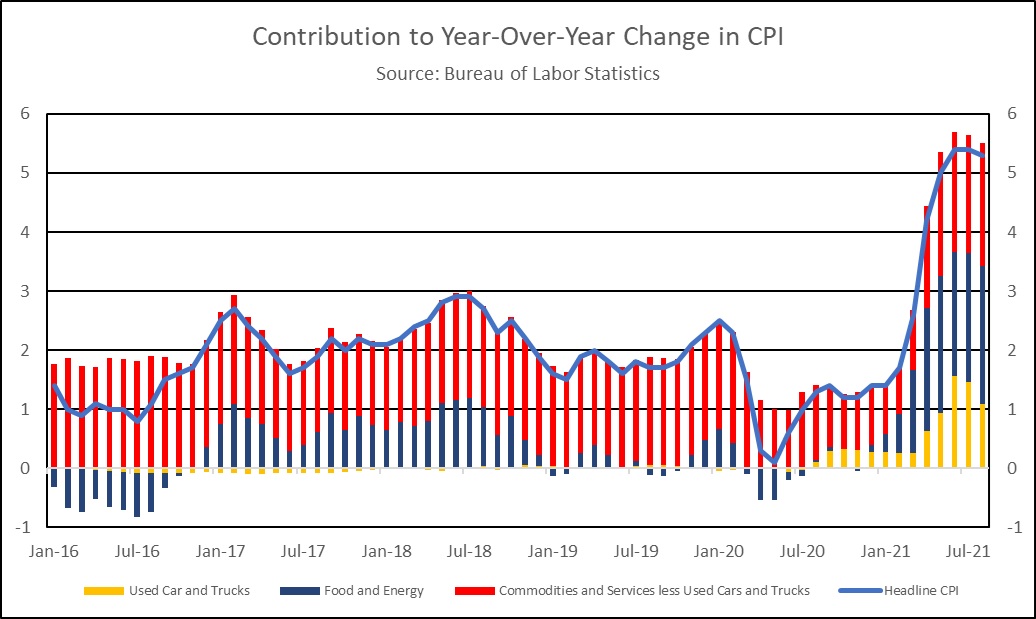

To help illustrate the impact that used car and truck prices have had on inflation, the above chart shows contributions to the yearly change in CPI. Used car and truck prices, in yellow, went from being a relatively insignificant part of CPI prior to the pandemic to accounting for about one-fifth of the annual increase in CPI from May to August. This single category was the biggest contributor to inflation over the last few months. The boost in used car prices has elevated the overall index drastically and the impact will likely reflect in the annual change numbers in CPI at least until mid-2022.

That being said, we are not certain that a slowdown or reversal in the rise of used car prices will automatically result in lower inflation. There are other price categories that have yet to recover to their pre-pandemic lows, and their recovery could offset the declines in used car and truck prices. Shelter prices, for example, are still rising at a slower pace than prior to the pandemic as people have been slow to move back into cities.[1] Meanwhile, increases in COVID-19 cases around the country have prevented hospitals from raising prices for many services. Thus, it is possible that inflation could rise even further over the next few months as services continue their recovery.

However, there is a risk of longer-term inflation. As the chart above shows, the contributions of energy and food to CPI have also increased over the last few months. Rising shipping and warehousing costs have had an adverse effect on food prices. These higher costs have forced firms to raise prices or accept lower margins. So far, firms have been reluctant to push all of the costs onto their consumers, but they may not have a choice if prices remain elevated. Additionally, energy prices have rallied over the last few months as demand has recovered. Demand for energy products could subside over time, while new climate restrictions could make it costlier to produce these energy products. Even though the recent ban on new drilling on federal land has not completely hampered production, it does appear that the industry could be headed for a decline in the future. In response to this threat, it appears that energy firms have now prioritized paying down debt and repaying shareholders over reinvesting into new drilling. If this trend continues and production falls, prices will likely rise.

In our view, the rise in inflation should decline over time as supply chain disruptions and other pandemic-related distortions subside. Nevertheless, we are not confident that inflation will revert to its pre-pandemic level. Our expectation is that inflation could start to stabilize around mid-2022.

[1] CPI is weighted by city population, thus prices in major cities such as New York are weighted heavier than prices in mid-sized cities like St. Louis.