Asset Allocation Weekly – Don’t Call It a Comeback! (September 17, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

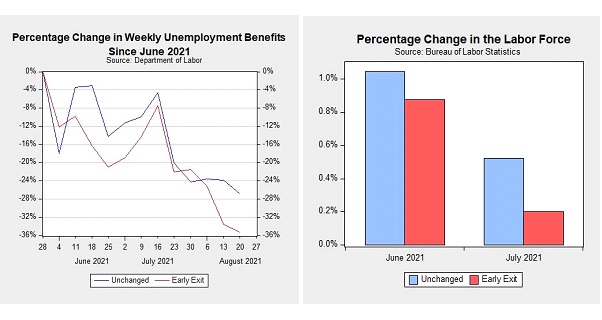

Last week, the federal government’s enhanced unemployment benefits of up to $300 per week expired nationwide. It has been speculated that the end of these benefits could lead to a surge of new entrants into the labor market. However, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) suggests this may not be true. In June and July, roughly half of the states in the country exited the program for enhanced unemployment benefits. Subsequently, the states that exited the program did see a sharper decline in the number of initial claims filed, but they had a slower increase in the number of workers entering the labor force. It should be noted that two months of data is not a long enough time period to draw any decisive conclusions about the labor market. That being said, if this trend continues, it may encourage the Federal Reserve to hasten its withdrawal of monetary stimulus.

The latest jobs report has led to speculation that the Fed could delay the withdrawal of its monetary stimulus. According to the BLS, the country added 235,000 jobs in August. This is less than a quarter of the jobs created in the previous month. The steep slowdown in job creation has led many to call into question the strength of the economic recovery. In anticipation of a possible delay in the withdrawal of monetary stimulus, investors sold off Treasuries and purchased tech stocks. On the day of the report, the NASDAQ closed at an all-time high, while the S&P dipped slightly.

Although the focus on employer payrolls makes sense, it may not be the most material data point when trying to gauge the Fed’s next policy move. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard has downplayed the importance of the payroll numbers in June, arguing that the labor market can still be tight even if payrolls remained below pre-pandemic levels. So far, the data supports this view. The latest JOLTS report showed that there are over two million more job openings than there are people looking for work. Over the last few months, firms have opted to raise wages in order to attract more workers.

The biggest drag on the labor force has come from workers on the extreme ends of the age spectrum. The youngest, excluding 16-19-year-olds, and oldest age cohorts have been reluctant to return to the labor force. Although higher wages may be enough to attract some younger workers, attracting older workers could prove to be more complicated. For these workers, there is no need to rush back into the workforce as they can transition into their Social Security retirement benefits once the pandemic benefits expire. If this happens, it could signal to the Fed that the labor market is too tight. As a result, the decision to wind down monetary stimulus may hinge on the willingness of older workers to reenter the workforce.

With enhanced unemployment benefits ending this month, the Fed will likely be paying closer attention to the labor force. In a recent interview, Bullard argued that the payroll data will likely be choppy from time to time but he expects the country to add 500,000 jobs per month this year. So far, the country is averaging 586,000 jobs per month. He also noted that he expects more people to reenter the labor force following the expiration of enhanced benefits. Given the comments he made in June, we suspect that he and possibly other policymakers may be more concerned with the number of people entering the labor force than the number of jobs created. In the event that workers do not return to the labor force, we expect there will be increased support for the Fed to escalate the pace of its stimulus drawdown. An early exit of its asset purchase program may give the Fed the ability to raise rates in a timelier manner. This outcome should increase interest rates, improving the outlook for shorter duration fixed income.