Author: Rebekah Stovall

Daily Comment (January 21, 2022)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA, and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EST] | PDF

Good morning! Today’s report begins with Treasury Secretary Yellen’s outlook on inflation. We then turn to a report from the Federal Reserve regarding digital currencies and comment on a few other U.S. economic and policy news items. Next, we discuss details about China’s investigation into the Ant Group. International news follows, and we wrap up with our pandemic coverage.

In an interview with CNBC, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated she expects inflation to slow down close to 2% by the end of the year. Her forecast assumes the pandemic is somewhat controlled by that time. Although we are more sanguine about inflation relative to our peers, we must admit that a prediction of 2% is a bit overly optimistic. In explaining her prediction, she mentioned that a key to lowering inflation would be to resolve the supply chain issues. Even though we agree that improving supply chains will help, our research suggests energy prices also must be addressed if the administration wants to successfully lower inflation.

In 2021, the average price of Brent Crude Oil rose nearly 60%, its sharpest rise in over 30 years. The strong rally in oil prices was driven by a surge in demand due to the reopening of the global economy, falling inventories, and shrinking capacity. We do not expect oil prices to have a similar rise in 2022, but a significant increase in oil prices will likely prevent inflation from reverting to 2% by year-end.

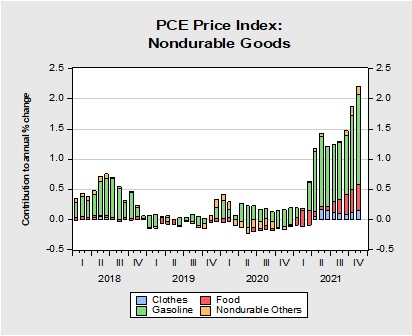

The chart above shows the primary driver in nondurable goods (which also includes food and apparel) inflation in 2021 was gasoline prices, a by-product of oil. With more analysts, including our firm, predicting the price of Brent Crude will reach $100 a barrel this year, we think it will be very difficult for inflation to fall to 2% in 2022. However, we still believe inflation will ease throughout the year to around 4.0-3.5%.

Economics and policy:

- The Federal Reserve released its report on central bank currencies on Thursday. The paper concluded that creating a digital version of the dollar will likely speed up payment delivery but could cause financial instability and lead to privacy concerns. The bank made no policy recommendation but stated it would only proceed with creating the currency with the backing of the executive branch and Congress.

- Secretary of State Antony Blinken and his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov met in Geneva on Friday. The two discussed a possible de-escalation of the situation at the Ukraine border. Although they reached no final agreement, Lavrov stated a willingness to continue talks. News of continued talks is a relatively positive development following Biden’s remark on Wednesday that suggested a “minor incursion” from Russia into Ukraine was inevitable. However, the U.S. is still preparing for the worst-case scenario. The Biden administration is looking into ways Russia might retaliate if removed from the SWIFT financial system. Additionally, the U.S. has given permission to NATO allies to send American-made weapons into Ukraine.

- The Senate Judiciary Committee advanced an anti-trust bill that would limit big tech companies’ ability to favor their own services.

- Federal agencies will raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour for all employees.

- The U.S. is working on a way to speed up the delivery of F-16 fighter jets to Taiwan. The new jets will help the region to intercept aggressive Chinese military planes.

China:

The Ant Group, an affiliate company of Alibaba (BABA, $131.03), has been implicated in a corruption scandal. A documentary alleged private companies made “unreasonably high payments” for private land to a brother of a Chinese Communist Party member in exchange for government favors. Although the Ant Group was not named directly in the documentary, public records seemed to link the group with the transaction. The crackdown on Alibaba shows Chinese regulators are still trying to rein in big tech companies.

International news:

- The push by the EU to label nuclear power and some natural gas sources as green energy has received some backlash. The decision appears to be in response to growing concerns that existing ESG restrictions will make it harder for countries to meet their energy consumption needs. The new designation would make it easier for nuclear power and natural gas firms to have access to additional financing.

- Russia announced it plans to hold military exercises with its entire fleet this month and next. The drills come after growing speculation that Moscow may stage an invasion of Ukraine.

- Germany would like to attract 400,000 qualified workers to help address demographic imbalances and labor shortages.

COVID-19: The number of reported cases is 342,928,762, with 5,576,274 fatalities. In the U.S., there are 69,309,309 confirmed cases with 860,248 deaths. For illustration purposes, the FT has created an interactive chart that allows one to compare cases across nations using similar scaling metrics. The CDC reports that 655,282,365 doses of the vaccine have been distributed, with 531,864,871 doses injected. The number receiving at least one dose is 250,028,635, the number of second doses is 209,842,610, and the number of the third dose, the highest level of immunity, is 82,450,772. The FT has a page on global vaccine distribution.

- EU countries are set to update their rules on traveling. The new rules will allow travelers with a COVID-19 certificate to avoid additional testing or quarantine if they are not coming from a high-risk area. The European Center for Disease Prevention and Control coronavirus map, which tracks the rise in cases for most of Europe, will be used to determine whether travelers will be required to undergo additional screening.

- There is growing concern that China will not be able to maintain its no-tolerance COVID-19 policy. The city has struggled to contain the virus despite extreme measures such as mass testing, stringent border controls, extensive contact tracing, and snap lockdowns. If COVID-19 cases continue to spread in China, it could lead to worsening supply chain problems.

Germany expects to see as many as 400,000 COVID-19 cases per day by mid-February.

Asset Allocation Quarterly (First Quarter 2022)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

- We anticipate that economic growth will continue, but at a more modest pace than last year, and the potential for a recession within our three-year forecast period remains low.

- The Fed’s prior intransigence on inflation has yielded to a more hawkish stance leading to expectations for the curtailment of balance sheet expansion and the probability of several rate hikes over the coming year.

- Among strategies with income as an objective, the former elevated equity allocations are modestly reduced, while the heavy tilt toward value and overweight to lower capitalization stocks are retained.

- Although the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar may remain elevated and could even modestly strengthen, global economic expansion mirrors that of the U.S. and valuations of international developed market companies are compelling.

- Risks associated with China lead to an exclusion of emerging market positions in all but the most aggressive strategy.

- A position in broad-based commodities, with an emphasis on oil, is employed across the array of strategies as is a position in gold given the advantages it affords during heightened geopolitical risk.

ECONOMIC VIEWPOINTS

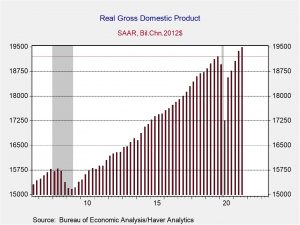

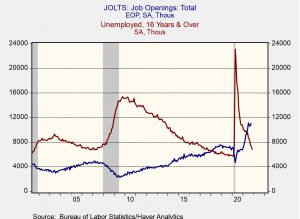

Although we recognize the elevated prints on inflation and GDP will become more muted in the coming months, as the base effects of comparative numbers from a year ago will not be as stark, continuing issues with supply chains and unfilled job openings temper our economic enthusiasm. We believe the U.S. economy has recently entered a mid-cycle of expansion and the potential for a recession, while above zero, remains low for our three-year forecast period. A policy mistake by the Fed is one of the more prominent risks to our case for modulating inflation, a steady increase in wages, and economic growth, particularly in services as COVID variants run out of letters in the Greek alphabet. Recently released minutes from the Fed’s latest meeting reveal a level of zealousness in addressing inflation through advancing the curtailment of balance sheet expansion as well as hiking the fed funds rate multiple times in 2022 and likely beyond. As contrasted with short-lived inflation stemming from supply chain issues, the concerns of the Fed appear to be centered on fighting more durable inflation in the form of steadily increasing wages and rents and their congruent effect on long-run inflation expectations. The Fed will effectively be attempting to navigate a narrow channel of reducing the more pernicious aspects of inflation without detrimental effects on the labor market or economic growth. Narrowing this tight channel further is the extraction of fiscal stimulus. The generous fiscal provisions of the past 20 months have either expired or are expiring, and the passage of further legislation, especially in an election year, looks increasingly unlikely. Given the Fed’s intention for a series of rate hikes, the risks increase for a policy mistake. Yet if the Fed is deliberate and studied in its tightening in an attempt to normalize policy, we believe the chances for a mistake are markedly reduced.

The economies of other developed countries are now mostly into expansion, mirroring the U.S. in terms of both rapid recoveries to pre-pandemic peaks as well as projected growth rates of over 5% for all of 2021, representing the highest rate of growth since the early 1990s. In response, several central banks have commenced reversals of their prior ultra-accommodative monetary policies. Although the ECB and BOJ are probably going to be exceptions, with the former projected to wind down its net purchases for just its pandemic response bond purchase program, the BOE, RBA, and BOC have fully curtailed their government bond purchase programs and have indicated their intentions to increase rates, joining the ranks of Brazil, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, and South Korea, which tightened monetary policy several months ago. Moreover, fiscal support largely expired at the end of 2021, particularly in European countries. Not only are supply bottlenecks and inflation as troublesome overseas as domestically, but the retraction of fiscal spending and monetary policy normalization produce a similar backdrop as in the U.S. Therefore, our expectation is that the global economy will continue to expand, albeit at a lower rate than last year. This expectation is tempered by the potential for policy mistakes, extended COVID mutations and related economic impact, and difficulties emanating from China. Beyond the saber-rattling toward Taiwan, concerns surrounding China include trade policies and premature loosening of credit conditions in the leveraged property market and the potential for corresponding negative effects on debt of other emerging markets.

STOCK MARKET OUTLOOK

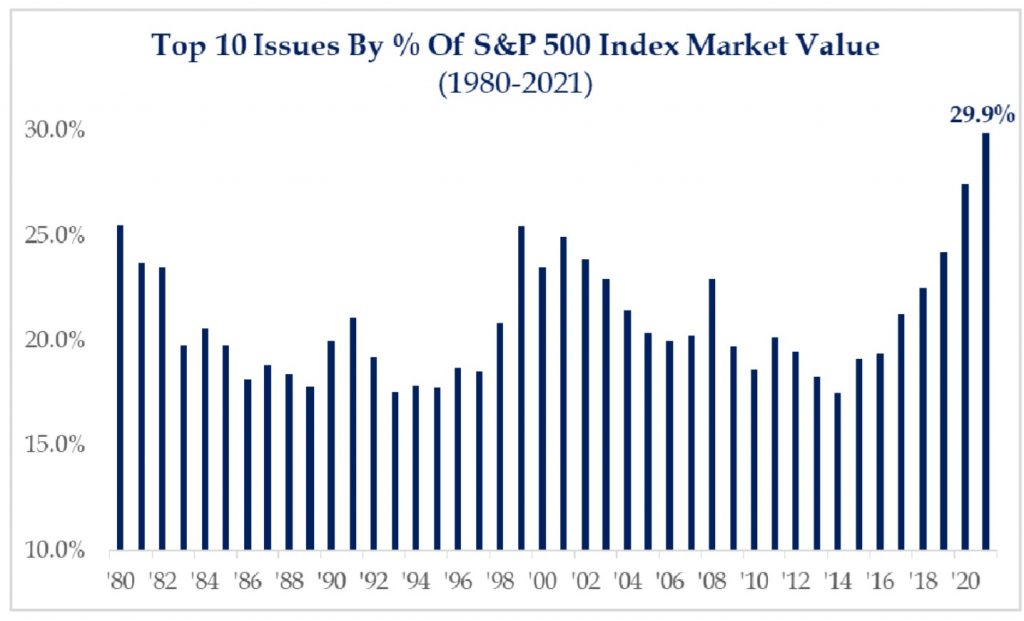

We expect earnings growth to continue over our forecast period, yet at a slower pace than the rapid growth experienced last year. Concisely, we expect growth to increase at a decreasing rate. Similarly, we expect bottlenecks, inflation, and COVID to be peaking as well. We believe we are in the early portion of the mid-cycle of economic expansion, thus more cyclical lower market capitalization companies have particular appeal as they benefit from lower valuations and can adapt more nimbly to changing economic conditions. In normal periods, bouts of inflation can contribute to a lowering of P/E ratios. Core inflation is expected around the 3% level, and while we have no illusions that this time will be different, we believe it will disproportionately affect the mega-cap companies that have grown to encompass an unwieldy proportion of the U.S. equity market. As the accompanying chart indicates, the concentration of the largest companies has reached a proportion never experienced in U.S. equities. In fact, the top six account for nearly 25% as of this writing, all of which are names with a tech-heavy influence. It is often argued that the late 1990s experienced a similar concentration yet with a dearth of earnings. Our belief is that even with solid earnings, the concentration will abate over our forecast period and, by extension, contribute to a lower aggregate P/E level on the S&P 500.

In order to ameliorate some risk we find inherent in the attenuation of holdings, we maintain a significant bias of 65% to value stocks, where the concentration is far less. In addition, within U.S. large cap equities, we maintain the more cyclically oriented sectors of Materials, Financials, and Housing, and introduce a defensive position in the Health Care sector. Across the array of strategies there is elevated exposure to lower market capitalizations owing to more favorable valuations and their potential to deftly navigate a changing inflationary picture and Fed tightening.

Beyond the U.S., favorable valuations are even more compelling than in lower capitalization domestic stocks. Even with a stable or moderately strengthening U.S. dollar, stocks in international developed markets, specifically the Eurozone and U.K., still harbor solid appeal based on traditional valuation metrics alone. Should a catalyst develop that reduces the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar, which is overvalued relative to almost every currency by historical measures, this will further benefit U.S.-based investors in international stocks. Although developed markets hold appeal, the heavy influence of China on emerging markets and its attendant risk results in a void to emerging market stocks in all but the most aggressive strategy, where the holding is explicitly ex-China.

BOND MARKET OUTLOOK

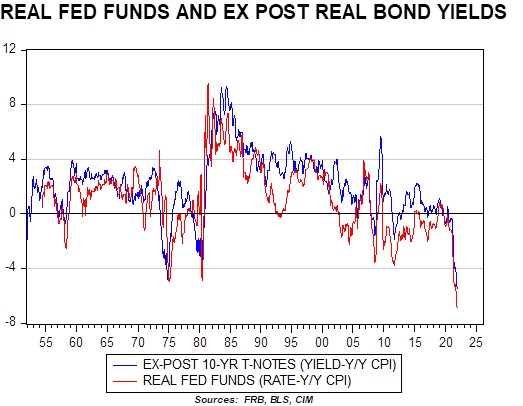

The anticipated termination of the Fed’s balance sheet expansion in March and the potential for the central bank to raise fed funds as many as four times this year leads to our modest expectations for bonds over the forecast period. As the accompanying chart indicates, real fed funds and the ex-post real 10-year Treasury note are at negative levels last experienced after the end of World War II. Although this does not necessarily portend dire consequences for bondholders, it introduces an element of caution that causes us to concentrate holdings in the short- and intermediate-term segments and reduce the prior heavy allocation to corporate bonds. Corporate bonds are near historically tight spreads. Similarly, the spreads of mortgage-backed securities [MBS] to maturity equivalent Treasuries are modestly tighter than average, leading to the exclusion of MBS in all strategies.

OTHER MARKETS

REITs have produced outsized returns over the past year. While the newer segments of data centers, communication towers, and warehouse fulfillment centers delivered another year of healthy returns, the traditional segments of hospitality, office, and retail fully recovered in 2021 from COVID-related investor fears. With REITs in the aggregate close to fully valued, especially in view of a more hawkish Fed, we find the potential risk/return profile to be more attractive in other equities.

Our expectation of a continuing global economic recovery, albeit at a less than frenetic pace, encourages an allocation to a broad-basket of commodities, with an emphasis on energy. We believe that the move away from oil will certainly not be abrupt; however, the restraint of capital for development of sources for new oil will hamper supply, while demand, though dampened, remains strong throughout our forecast period. Accordingly, we position a broad commodity ETF, the majority of which is in oil and its derivative products, across all strategies. In addition, we retain a position in gold across all strategies given its attraction as a haven from heightened geopolitical risk.

Confluence of Ideas – #24 “The 2022 Outlook” (Posted 1/20/22)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #1 “What Would a U.S.-China War Look Like?” (Posted 1/18/22)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – What Would a U.S.-China War Look Like? (January 18, 2022)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

(Note: As we shift to a bi-weekly publication schedule for this report in 2022, we introduce the accompanying Geopolitical Podcast, now available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify | Google)

We’ve written extensively about the worsening geopolitical tensions between the United States and China, which have already affected investors. For example, the Trump administration’s tariffs on Chinese imports have skewed economic developments in each country. Businesses in each country have suffered, while others have benefitted.

Looking ahead, the risks are even bigger. It’s important to stress that a U.S.-China war is not inevitable. On each side, the top leadership probably wants to avoid war. However, as each country flexes its muscles and pushes back against the other, there is a growing risk of miscalculation or mistake that leads to shooting and bloodshed. Even if the conflict became “World War III,” it would not necessarily look the same as World War II. A conflict between today’s two greatest powers would exemplify a new, unique form of modern warfare in terms of the domains in which it would be fought, the weapons utilized, the tactics and strategies employed, the alliances facing each other, and the goals pursued by each side. This report describes the likely lead-up to such a war and how it might be fought. As always, we wrap up with a discussion of the likely ramifications for investors.

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #66 “The Path of Monetary Policy” (Posted 1/10/22)

Asset Allocation Weekly – #65 “What’s Causing the Yield Curve to Flatten?” (Posted 12/17/21)

2022 Outlook: The Year of Fat Tails (December 16, 2021)

by Mark Keller, CFA, Bill O’Grady, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

Summary:

- We don’t expect a recession in 2022. Real GDP growth will range between 3.0% to 3.5%. Inflation remains elevated, though price pressures will likely subside in H2 2022. We expect the core PCE deflator, the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation, to decline into a range between 3.5% to 3.0%. Overall CPI will decline into a range of 4.0% to 3.5%. So, inflation will remain elevated but should ease. Labor markets should slowly normalize, with unemployment reaching 4.0% by year’s end.

- The 10-year T-note will end the year with a yield of 1.85%, with an intra-year peak of 2.20%. Our base case is that the Federal Reserve will end its balance sheet expansion by mid-2022, but the first rate hike is more likely to come in Q1 2023.

- The S&P 500 will reach 5000 in 2022, approximately 6.0% higher than the expected 4700 at year-end 2021. Given liquidity conditions, we would carry an upside bias to this forecast. On the negative side, inflation is elevated, multiples are stretched, and bottlenecks and rising labor costs could eventually hurt margins. On the positive side, liquidity is ample, especially in the top 10% of households, and will tend to support equities. We favor value over growth and small caps over large caps. We remain favorable to foreign stocks.

- We still view the dollar as overvalued, but some sort of exogenous catalyst will likely be necessary to change the current bullish sentiment.

- We are bullish commodities and believe we are in the early stages of a broader bull market. Gold is undervalued on a long-term basis but is facing competition from bitcoin.