Author: Rebekah Stovall

Weekly Geopolitical Report – The 2022 Geopolitical Outlook (December 13, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady & Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

(This is the last WGR of 2021; the next report will be published on January 18, 2022. Starting in 2022, we will shift to a bi-weekly publication schedule and will add a new Geopolitical Podcast with each report.)

As is our custom, in mid-December, we publish our geopolitical outlook for the upcoming year. This report is less a series of predictions as it is a list of potential geopolitical issues that we believe will dominate the international landscape for 2022. It is not designed to be exhaustive; instead, it focuses on the “big picture” conditions that we believe will affect policy and markets going forward. They are listed in order of importance.

Issue #1: China

Issue #2: Russia

Issue #3: Germany

Issue #4: The Crisis in Ethiopia

Issue #5: Rising Food Prices

Issue #6: The Energy Transition

Issue #7: The Failure of the Iran Nuclear Negotiations

Odds and Ends: This section is for concerns that may affect the world in 2022 but didn’t rise to the level of an issue on our list.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #64 “The Omicron Problem” (Posted 12/10/21)

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Plunging U.S. Service Exports (December 6, 2021)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

When people think about a country’s exports, imports, and trade balance, they often focus only on physical goods (sometimes referred to as “commodities” or “merchandise”). That makes some sense, given that physical goods account for the majority of international trade for most countries. Trade in physical goods can also be volatile, and it can have big implications for a country’s domestic politics. All the same, services are also a big part of international trade. In this report, we take a close look at the role of services in U.S. trade. We highlight how U.S. trade in services plummeted as a result of the global COVID-19 pandemic, and how it’s now starting to bounce back. We end with a discussion of how that plunge and budding rebound may affect investors.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #63 “An Update on Gold” (Posted 12/3/21)

Daily Comment (November 30, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA

[Posted: 9:30 AM EST] | PDF

In today’s Comment, we open with highlights from the U.S. labor market, U.S. relations with China and Russia, and a small number of other international developments. However, the bulk of our report deals with the new Omicron variant of the coronavirus, which today has again sparked sharp volatility in the world’s financial markets.

U.S. Labor Market: Against the backdrop of a nationwide labor shortage that is driving up wages and encouraging labor action, an official with the National Labor Relations Board ruled that Amazon (AMZN, 3,561.57) improperly impeded an April unionization vote that ultimately failed and ordered that the vote be held again. The company will have the right to appeal the ruling to the full NLRB, but the body could schedule the re-vote before that happens.

United States-China: Vice Admiral Karl Thomas, commander of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, called for as many as eight U.S. and allied aircraft carriers to be deployed to Asia-Pacific waters in order to deter China and Russia from making aggressive geopolitical moves in the region. That would mark a huge increase in allied carrier deployments in the region, underscoring the seriousness with which at least some U.S. military leaders see the challenge from China and Russia in the coming years.

China: In a sign that the government’s crackdown on big, powerful technology companies has not yet ended, six different regulatory agencies today announced a raft of new rules to rein in the country’s ride-hailing industry. Among other things, the new rules will limit the fees companies can earn from each ride they dispatch, incentivize them to make some drivers formal employees, and urge them to provide benefits such as insurance for their drivers.

NATO-Russia-Ukraine: Foreign ministers from the NATO countries are meeting in Latvia today to forge a response to Russia’s troop buildup around Ukraine, which U.S. intelligence officials have warned could point to a Russian invasion in the coming months. The ministers will need to strike a difficult balancing act between sending a tough warning to Moscow while not over-committing to the defense of Kiev.

Iran Nuclear Deal: At the latest round of talks to re-implement the 2015 deal limiting Iran’s nuclear program, Iranian negotiators yesterday doubled down on the tough demands they would require before agreeing to a renewed deal. For example, the Iranians continued to refuse to talk directly with the U.S. side, and they demanded that any resumption of the deal would require the U.S. to first dismantle all sanctions imposed since it walked away from the agreement in 2018. Prospects for a renewed deal appear slim, raising the prospect of future destabilizing moves ranging from an Iranian break-out to a nuclear weapon or an Israeli-led attack to prevent that from happening.

Barbados-United Kingdom: Barbados officially became a republic today, nearly 400 years after the English first set foot on the Caribbean island. As a result, Queen Elizabeth II is now head of state for just 15 realms, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and Jamaica.

COVID-19: Official data show confirmed cases have risen to 262,312,703 worldwide, with 5,211,147 deaths. In the U.S., confirmed cases rose to 48,440,107, with 778,653 deaths. (For an interactive chart that allows you to compare cases and deaths among countries, scaled by population, click here.) Meanwhile, in data on the U.S. vaccination program, the number of people who have received at least their first shot totals 232,792,508. The data show that 70.1% of the U.S. population has now received at least one dose of a vaccine, and 59.3% of the population is fully vaccinated.

Virology

- In today’s key virology news, CEO of Moderna (MRNA, 368.51) Stéphane Bancel predicted in an interview with the Financial Times that existing vaccines will be much less effective at tackling the new Omicron variant than earlier strains of coronavirus. Just as unsettling, he warned that it would take months before pharmaceutical companies could manufacture new variant-specific jabs at scale.

- According to Bancel, “I think [the change in effectiveness] is going to be a material drop. I just don’t know how much because we need to wait for the data. But all the scientists I’ve talked to…are like, ‘This is not going to be good’.”

- With drug firms warning that the current vaccines might have to be modified to retain control over the pandemic, economic prospects and returns on risk assets are once again in question. As we mentioned in our Comment yesterday, early indications are that Omicron may be more transmissible but less lethal than previous variants, which at some level could be a positive outcome. Scientists probably still need at least a couple of weeks of study to get a decent feel for how Omicron behaves. All the same, Bancel’s comments underscore that the situation remains fluid, and a more negative assessment of Omicron might evolve. As shown by today’s market declines in Europe and Asia, that could leave markets volatile in the coming weeks.

- Similarly, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (REGN, 654.40) said preliminary tests indicated that its antibody drug cocktail to treat COVID-19 lost effectiveness against the Omicron variant. Outside scientists said an antibody treatment from Eli Lilly (LLY, 254.83) also appeared to lose effectiveness against the mutation. Both findings are preliminary, but they have contributed to today’s market angst regarding Omicron.

- In light of the threat from the new Omicron variant, the CDC yesterday recommended that everyone 18 and older get an additional shot after completing their first course of vaccination. That marked a step up from the agency’s stance earlier this month, when it merely encouraged boosters for those 50 and above and said people ages 18 and above could get an additional dose. Indeed, some experts believe that having a booster may soon become a requirement to be considered “fully vaccinated.”

- Reports indicate that the FDA, as early as next week, may approve use of the vaccine from Pfizer (PFE, 52.40) and BioNTECH (BNTX, 362.52) as a booster in youths aged 16 and 17. As of now, the vaccine is approved as a booster only for those 18 and older.

Economic and Financial Market Impacts

- In testimony prepared for the Senate Banking Committee this morning, Fed Chair Powell says the new Omicron variant could intensify the supply-chain disruptions that have fueled this year’s surge in inflation. The testimony highlights how the new variant could put the Fed in a difficult position in the coming months if it exacerbates inflation, while also holding more workers back from seeking employment, which could lead wages to continue accelerating.

- In an address to the nation regarding the new Omicron variant, President Biden yesterday said the mutation is “a cause for concern, not a cause for panic.” He also said he would unveil a plan on Thursday for tackling the virus this winter “not with shutdowns and lockdowns, but with more widespread vaccinations, boosters, testing, and more.”

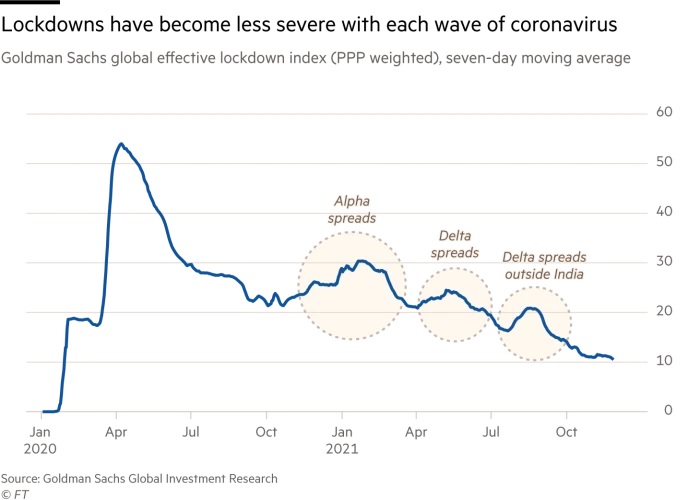

- The commitment to not focus on new economic lockdowns underscores the fact that many world leaders will be politically constrained from using such an approach to battle the Omicron mutation, at least unless it proves to be much more lethal than now known. Not only has the long battle against COVID-19 spawned intense popular backlash against lockdowns, but the rollout of vaccination programs has probably also made lockdowns less necessary.

- New lockdowns could be imposed in some places, as they already have been in some European nations, but for now it looks like we won’t see the widespread, nationwide lockdowns seen earlier in the pandemic. Indeed, global lockdowns have continued to trend downward throughout the period since the pandemic first began, as shown in the chart below.

Weekly Geopolitical Report – The Geopolitics of the Strategic Petroleum Reserves (November 22, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

(NB: Due to the Thanksgiving holiday, the next report will be published on December 6.)

During the 1970s, the world economy suffered through two oil shocks. The first, in 1973, was caused by the Yom Kippur War. The U.S. supported Israel, and the Arab states retaliated with an oil embargo. In 1979-80, the Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War disrupted oil flows from the Middle East, leading to another oil spike. Due to these events, the OECD, through the auspices of the International Energy Agency (IEA), created a member Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) system. This system was designed to be an emergency backup supply of oil and oil products that could be shared to prevent panic buying of oil and to ensure that the economic damage that was suffered due to the 1973 and 1979 oil shocks would never be repeated.

However, as the world moves away from fossil fuels, these SPRs could be holding inventory that will no longer be needed. Simply put, governments that hold reserves could find themselves with worthless inventory. Merchants often find themselves in this situation; a seasonal item remains on the shelf when a season is winding down. A decision has to be made—cut the price to sell out the item before the season ends and lose margin or hold the good and hope that buying emerges to maintain margin. With the SPRs, governments may face the problem of what to do with this oil in the face of falling demand. The decisions that these governments make will affect oil prices, consumers, and producers in the coming years.

We will begin our analysis with a history of the SPRs, explaining how they work, who has them, and how much oil they contain. From there, we will discuss the difference between a buffer stock and a reserve. Next, we will examine the role of climate change policy on SPR management. How OPEC+ manages its production policy in light of SPR releases will follow. We will close with market ramifications.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #62 “The Composition of the FOMC” (Posted 11/19/21)

Weekly Geopolitical Report – The Special Relationship (November 15, 2021)

by Thomas Wash | PDF

Ever since the United Kingdom defeated the Spanish Armada in the 16th century, it has typically kept Europe at arm’s length. The victory not only showed that the British could successfully defend itself from invasion, but that it was an important power in Europe. This newfound confidence along with the Commonwealth’s growing manufacturing prowess gave it an air of superiority over its continental colleagues. After defeating France in the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, therefore becoming the world’s superpower, this sentiment became deeply entrenched into the British psyche.

However, British sentiment took a hit after World War II. As the second war on the continent in forty years, it pushed the U.K. to the brink of collapse. Humbled, the British pursued peaceful coexistence with the rest of Europe as they attempted to rebuild their country. They not only sought collaboration with the rest of Europe but also supported greater integration. That being said, the U.K. has struggled to accept a subordinate role within Europe as it seems to believe it is superior. As recently as December 2020, Education Secretary Gavin Williamson joked that the U.K. was the first developed country to approve the coronavirus vaccine because it “was a much better country” than others.

Understandably, British hubris has often rubbed other European countries the wrong way. The underlying friction between the two sides came to a head after the European Union rejected the U.K.’s request to be exempted from the EU’s immigration program. This decision not only paved the way for Brexit but may have also set the stage for a potential trade war. In this report, we will examine the history of British-EU relations, discuss the Brexit vote and fallout, and briefly review how the relationship has changed since the U.K. left. As always, we will end with a brief discussion of market ramifications.