Author: Rebekah Stovall

Asset Allocation Weekly – Globalization Isn’t What It Used to Be (October 15, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep…But, most important of all, he regarded this state of affairs as normal, certain, and permanent, except in the direction of further improvement.

— John Maynard Keynes

Over the last 30 years, we have grown accustomed to all the benefits of globalization. During this time, goods prices not only became more stable, but the delivery of goods was fast and reliable. However, this hasn’t been true over the last few months. Since the start of the pandemic, countries that rely heavily on global supply chains have struggled to receive goods from other countries. Supply constraints have made it difficult for firms to meet domestic demand. This dynamic has put the Fed in a bit of a quandary as it struggles to determine the path of policy. In this report, we discuss how supply chain disruptions have led to the recent rise in inflation and how the Fed might respond if prices remain elevated.

A key element to globalization is stability. In a stable world, firms are better positioned to absorb supply shocks. When the world is stable, firms are able to deal with isolated supply disruptions by going to different suppliers for goods or by finding cheaper alternatives. For example, when the price of coal goes up, firms generally purchase more natural gas and vice versa. Additionally, when the swine flu led to a shortage of pork products in China, the Chinese began importing pork from the U.S. In a stable world, shortages in one part of the world can be made up by an increase in production in other parts of the world. However, the dynamic changes when there is a universal shock like a war or pandemic.

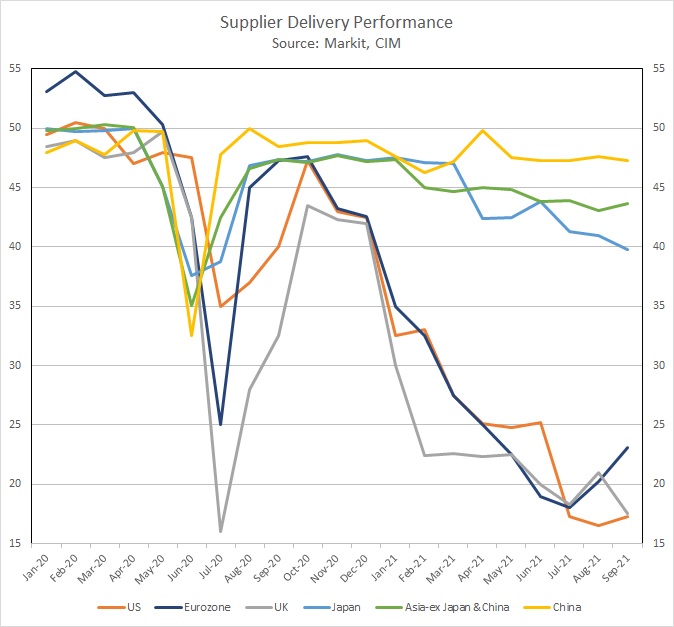

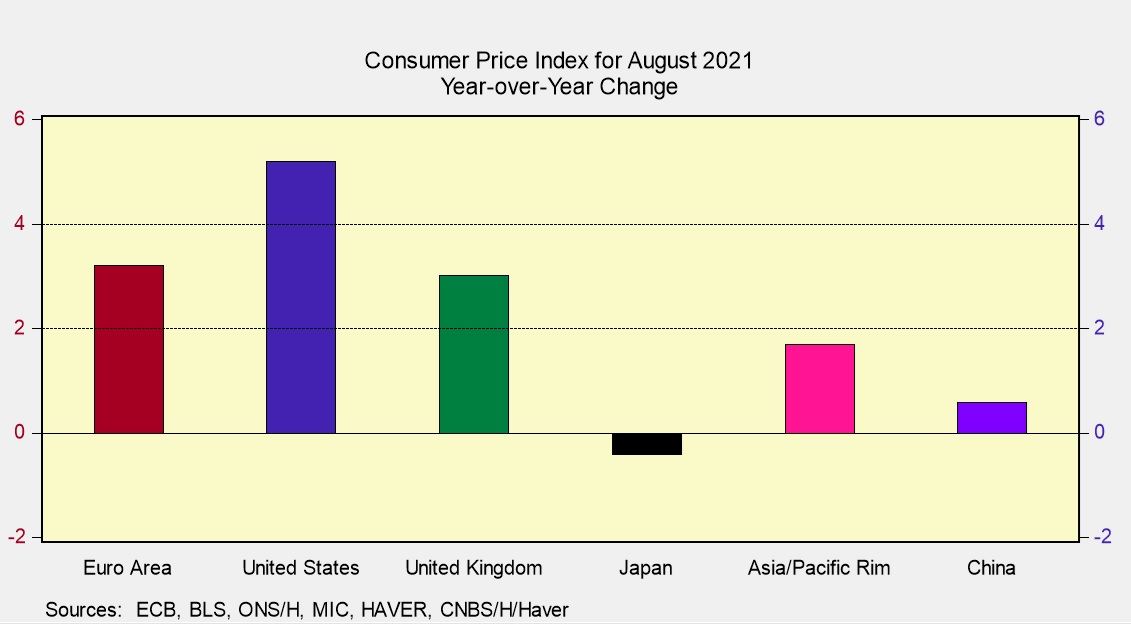

The pandemic has shown that globalization is ill-suited to deal with global supply shocks. The chart above shows that over the last few months, the U.S., U.K., and Eurozone, each of which relies heavily on outsourcing from Asia, have seen a steep decline in their supplier delivery performance. However, Asian nations, where there is less dependence on outsourcing, have seen their supplier delivery performance remain relatively stable. Furthermore, there does seem to be an inverse correlation between supplier delivery performance and inflation. The U.S., U.K., and Eurozone are all experiencing increases in inflation not seen in their respective countries in more than a decade. Meanwhile, Asian nations have seen their inflation fall below the standard target of 2%. The regional discrepancies between the rates of inflation highlight the impact the pandemic has had on global supply chains.

We suspect that as long as supplier delivery performance remains slow, it will be difficult for inflation to fall anytime soon in the U.S., U.K., and Eurozone. As a result, the Federal Reserve will face increasing pressure to react to higher inflation. After all, a lack of response would threaten its credibility and might undermine its independence. There are elements of the financial markets that would like the central bank to raise rates in order to contain inflation, while populist politicians would like it to maintain easy monetary policy to ensure that wages keep rising and firms keep hiring. Angering the former could result in investors losing faith in the dollar, while angering the latter could lead to more political scrutiny.

Additionally, there is still the chance that raising rates in this environment may lead to undesired outcomes. Although higher rates could lower inflation by decreasing demand, they could also make it more expensive for firms to expand supply and maintain employment. The former may be the expected outcome, but the latter still presents a risk. Given the unpredictability of this pandemic, it is difficult to determine which outcome will prevail. As a result, raising rates may increase the likelihood of recession. This should prevent the Fed from raising rates sharply.

In conclusion, the steep slowdown in supplier delivery performance suggests that inflation will likely remain higher for longer. There will be increasing pressure on the Fed to tighten policy or risk undermining the central bank’s inflation credibility. At the same time, much of the pandemic’s impact on supply chains is temporary and price pressures should be mitigated as the pandemic is resolved. We expect the Federal Reserve to slow its balance sheet expansion initially and take a wait-and-see approach to raising policy rates. The risk of moving too soon is that it raises the possibility of needlessly stalling the improvement in the labor markets. The risk of moving too late could undermine confidence in the dollar and raise inflation expectations. The chances of a policy error are rising, and we will be monitoring the path of policy closely in the coming months.

Weekly Geopolitical Report – AUKUS (October 11, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

On September 15, the leaders of the U.S., U.K., and Australia announced a new security relationship which includes a nuclear submarine arrangement with Australia. Although it will likely take a couple of decades before Australia will have its own indigenous nuclear propulsion vessels, the treaty means that the U.S. and U.K. will likely begin sharing nuclear technology and other weapons systems.

The announcement not only marked the beginning of a new security relationship in Asia for the U.S. and U.K., but it also marked the end of another one, a $60 billion defense arrangement that France had with Canberra. France had previously agreed to provide Australia with diesel/battery submarines, but this new deal scuttled the French arrangement. The French were incensed; ambassadors were recalled, and European governments denounced the new arrangement.

It is not a huge surprise that the French were upset, but the degree of the reaction seemed strong given the violation. Diesel submarines pale in comparison to the capabilities of nuclear propulsion. The former is only useful in coastal protection. They need to resurface to use the diesel engines to recharge batteries; during this period, they are vulnerable to attack. They also require regular refueling. Nuclear submarines don’t need to resurface and can extend their patrol range significantly compared to a diesel-powered vessel. When the deal was made in 2016, diesel subs may have been adequate for the risks Australia perceived. That is no longer the case. So, it should have come as no surprise that Australia would consider an upgrade. Although France has nuclear propulsion technology, it is not as effective as American technology.

The U.S. decision to create this new security arrangement, Australia’s acceptance, the U.K. decision to join, and the reaction of France all reflect an evolving geopolitical situation in Asia. In this report, we will discuss why the three nations decided to create a new pact. From there, we will offer a short geopolitical analysis of Europe, followed by an examination of the French and European reactions. We will close with market ramifications.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #56 “Has Bitcoin Become a Substitute for Gold?” (Posted 10/8/21)

Asset Allocation Weekly – Has Bitcoin Become a Substitute for Gold? (October 8, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

Over the last half-decade, one of the most dramatic developments in finance has been investors’ embrace of cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. Once considered merely an exotic technology with little relevance to investment portfolios, Bitcoin has now become a popular tool for investing. One reason for its popularity is that some investors see Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as a substitute for gold and other precious metals in the face of the currency debasement implied by today’s loose fiscal and monetary policies. This report takes a quick look at whether Bitcoin can really be seen as a substitute for gold.

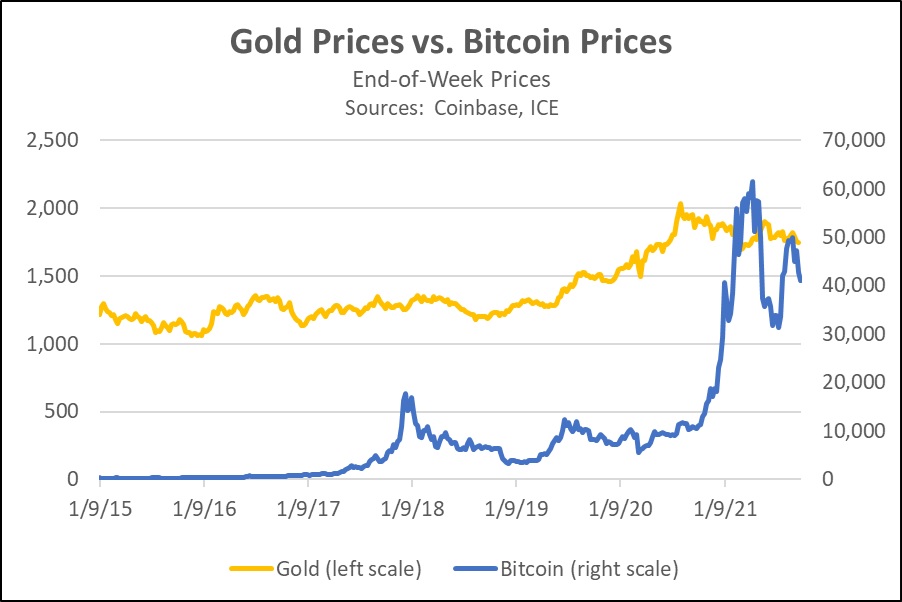

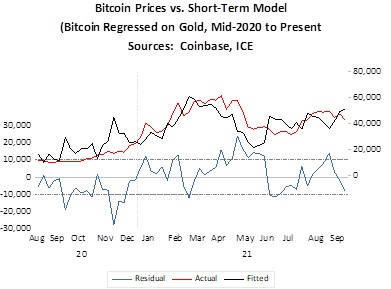

Although Bitcoin was invented in 2008, we rely on the pricing data from cryptocurrency exchange Coinbase starting in 2015, when Bitcoin trading really began to take off. As shown in the chart below, Bitcoin prices and gold prices have both risen from the beginning of 2015 to the present. Over the entire period, weekly Bitcoin and gold prices have had a positive correlation of approximately 0.71. Similarly, a simple regression model relating Bitcoin prices to gold prices suggests a strong positive relationship between the two. In that model, the weekly change in gold prices explains almost half the weekly change in Bitcoin prices.

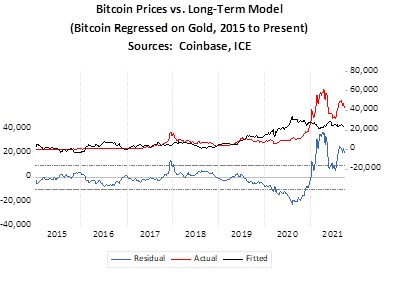

Even though Bitcoin and gold prices have both risen over the last six and a half years, Bitcoin has often diverged widely from the trend in gold prices, and our analysis suggests the relationship between the two assets has recently flipped. As shown in the chart below, actual Bitcoin prices since mid-2020 have diverged widely from what the long-term relationship would suggest.

Importantly, a shorter-term model relating Bitcoin prices to gold prices only from August 2020 to the present suggests their relationship has reversed, most likely because investors now see Bitcoin as a true substitute for gold rather than just a complementary asset as in the prior period. Since August 2020, the correlation between Bitcoin and gold prices has come in at -0.80, suggesting that rising Bitcoin prices are now associated with falling gold prices. A short-term regression model covering August 2020 to the present not only confirms that the two asset prices now move in opposite directions, but the model also does a better job of explaining the change in Bitcoin prices. One version of the short-term model using gold prices lagged by four weeks and explains almost 70% of the change in Bitcoin prices.

This evidence suggests that as Bitcoin trading expanded and more investment funds have been channeled into the asset, it has taken on the characteristics of a substitute for gold. At first glance, this makes sense. As the world’s fiat currencies are increasingly threatened by loose fiscal and monetary policies, the limited supply of Bitcoin makes it look like it could retain its value, just as the limited supply of gold does. Indeed, Bitcoin has features that are even more attractive than gold, such as being much easier to transfer among investors and cheaper to hold (you don’t need a warehouse or security guards for your Bitcoin, after all!). All the same, we think investors should be wary about trying to substitute Bitcoin for gold. As we saw in China over the last week, governments intent on preserving their sovereignty and issuing their own central bank digital currencies could outlaw Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies at any time or at least impose onerous regulations that would undermine their value. In other words, investors looking to protect themselves from currency debasement should probably continue to favor gold and other precious metals over cryptocurrencies.

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Afghanistan, Part IV: China (October 4, 2021)

by Thomas Wash | PDF

In Part I of this report, we reviewed the history of Afghanistan and why great powers have fought over it for centuries. Part II examined how the United States exit from Afghanistan will affect Pakistan, India, and Iran. Last week, Part III focused on how the U.S. exit will play out for Russia and the Central Asian countries. This week, we wrap up the series with a look at the implications for China and beyond, along with a discussion of the overall investment ramifications of the U.S. withdrawal.

Historically, China has tried to maintain a relatively low profile in Afghanistan. However, the U.S. troop withdrawal from the region has forced China to confront the problems that it has hoped to avoid. Without a U.S. presence in the region, Islamist extremism could potentially run rampant along Chinese borders. Additionally, instability in Afghanistan could hinder Chinese efforts to expand its influence into Central Asia and the Middle East. As a result, we suspect that China will embark on a potentially costly effort to fill the power vacuum left by the U.S. in Afghanistan. In this report, we will discuss how the U.S. withdrawal impacts China and how China may look to stabilize the region.

Asset Allocation Weekly – #55 “The Prices We Don’t See” (Posted 10/1/21)

Asset Allocation Weekly – The Prices We Don’t See (October 1, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

For four consecutive months, consumer prices as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have risen 5% from the prior year. The pace of inflation has sparked concerns that the Federal Reserve may be wrong in describing inflation as being transitory. However, our research suggests there may be more validity to the Fed’s claim than meets the eye. In this report, we discuss some evidence supporting the argument that inflation will be transitory. We also discuss the possibility that inflation may last longer than expected as well as the length of time in which we expect inflation to normalize.

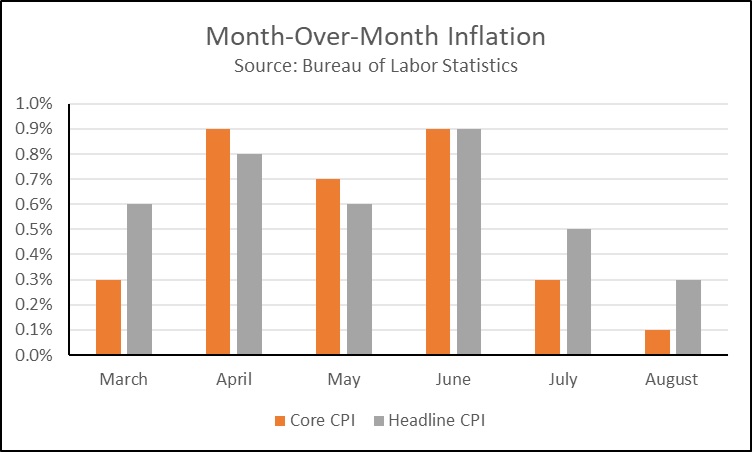

The most recent CPI report showed that inflationary pressures have eased sharply over the last two months. Monthly inflation (which is more sensitive to incremental change compared to annual comparisons) as measured by the CPI excluding the volatile food and energy components (Core CPI) went from a 30-year high in April to benign levels in August. The reduction in inflationary pressures coincided with a steep deceleration in the month-to-month inflation of used cars and trucks. In August, used car and truck prices fell 1.5% from the prior month. The decline in used car and truck prices likely relieved much of the pressure on the overall price index.

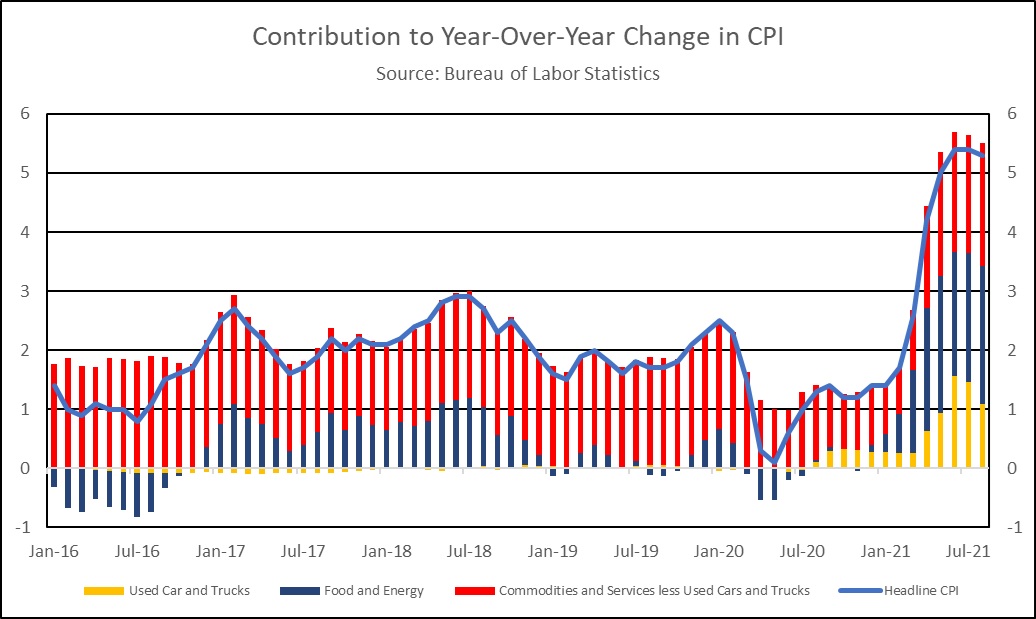

To help illustrate the impact that used car and truck prices have had on inflation, the above chart shows contributions to the yearly change in CPI. Used car and truck prices, in yellow, went from being a relatively insignificant part of CPI prior to the pandemic to accounting for about one-fifth of the annual increase in CPI from May to August. This single category was the biggest contributor to inflation over the last few months. The boost in used car prices has elevated the overall index drastically and the impact will likely reflect in the annual change numbers in CPI at least until mid-2022.

That being said, we are not certain that a slowdown or reversal in the rise of used car prices will automatically result in lower inflation. There are other price categories that have yet to recover to their pre-pandemic lows, and their recovery could offset the declines in used car and truck prices. Shelter prices, for example, are still rising at a slower pace than prior to the pandemic as people have been slow to move back into cities.[1] Meanwhile, increases in COVID-19 cases around the country have prevented hospitals from raising prices for many services. Thus, it is possible that inflation could rise even further over the next few months as services continue their recovery.

However, there is a risk of longer-term inflation. As the chart above shows, the contributions of energy and food to CPI have also increased over the last few months. Rising shipping and warehousing costs have had an adverse effect on food prices. These higher costs have forced firms to raise prices or accept lower margins. So far, firms have been reluctant to push all of the costs onto their consumers, but they may not have a choice if prices remain elevated. Additionally, energy prices have rallied over the last few months as demand has recovered. Demand for energy products could subside over time, while new climate restrictions could make it costlier to produce these energy products. Even though the recent ban on new drilling on federal land has not completely hampered production, it does appear that the industry could be headed for a decline in the future. In response to this threat, it appears that energy firms have now prioritized paying down debt and repaying shareholders over reinvesting into new drilling. If this trend continues and production falls, prices will likely rise.

In our view, the rise in inflation should decline over time as supply chain disruptions and other pandemic-related distortions subside. Nevertheless, we are not confident that inflation will revert to its pre-pandemic level. Our expectation is that inflation could start to stabilize around mid-2022.

[1] CPI is weighted by city population, thus prices in major cities such as New York are weighted heavier than prices in mid-sized cities like St. Louis.

Business Cycle Report (September 30, 2021)

by Thomas Wash | PDF

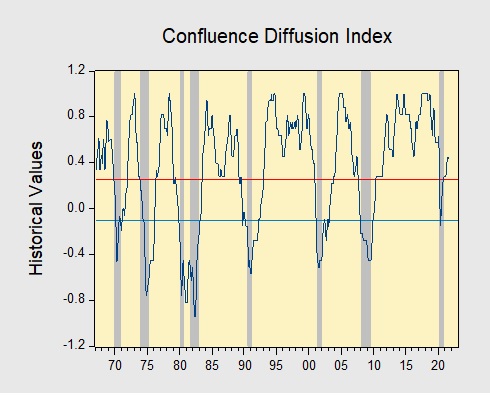

The business cycle has a major impact on financial markets; recessions usually accompany bear markets in equities. The intention of this report is to keep our readers apprised of the potential for recession, updated on a monthly basis. Although it isn’t the final word on our views about recession, it is part of our process in signaling the potential for a downturn.

In August, the diffusion index rose further above the recession indicator, signaling that the recovery continues. In the financial markets, a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases led to a modest sell-off in equities throughout the month. Meanwhile, construction and manufacturing activity improved due to stable levels of demand. Lastly, a huge miss in employment payrolls led to doubts about the strength of the recovery. As a result, eight out of the 11 indicators are in expansion territory. The diffusion index rose from +0.4545 to +0.4697, remaining well above the recession signal of +0.2500.

The chart above shows the Confluence Diffusion Index. It uses a three-month moving average of 11 leading indicators to track the state of the business cycle. The red line signals when the business cycle is headed toward a contraction, while the blue line signals when the business cycle is headed toward a recovery. On average, the diffusion index is currently providing about six months of lead time for a contraction and five months of lead time for a recovery. Continue reading for a more in-depth understanding of how the indicators are performing and refer to our Glossary of Charts at the back of this report for a description of each chart and what it measures. A chart title listed in red indicates that indicator is signaling recession.