Daily Comment (August 23, 2016)

by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It was another quiet overnight session, typical of late summer. The flash PMI data came in fairly strong (details below), easing some concerns about the economy post-Brexit. However, until Britain actually leaves the EU, it is almost impossible to determine what the actual impact will be, simply because we don’t know the terms of the exit.

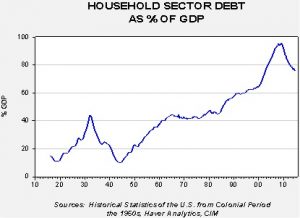

The real story this week is Fed Chair Yellen’s Jackson Hole speech on Friday. As best we can tell, the Fed and the world’s other industrialized central banks are starting to realize that the economy isn’t normalizing as they had projected it would since 2009. El-Erian’s “new normal” has come to pass, meaning that we live in a world of low growth and low inflation. We believe there are multiple reasons for low inflation and persistently slow growth. The primary culprit is the level of household debt; we are in a period of deleveraging, which tends to foster slow economic growth as household are less likely to borrow.

The key to a debt problem is resolution; society has to decide how to assign the bad debt losses. There are essentially three ways to address a bad debt problem. The debtors can shoulder the burden and are forced to cut their spending and increase their savings to service the debt. The creditors can carry the burden through repudiation or restructuring. Lastly, a third party can settle the debt and favor either side; in other words, if the outside party buys the debt at full face value, then the creditors are saved (of course, the debtors are too) and the third party bears the burden. Or, the outside party can buy the debt at a discount and force the creditor to bear some of the losses.

Such negotiations are political in nature. In Europe, for example, the debtors have carried nearly all the burden, which is why the economies of Greece, Spain, et al. have been so weak. In the U.S., the debtors have shouldered most of the burden. We note that during the Dodd-Frank negotiations, Senator Frank toyed with mortgage “cram downs” which would have forced principal losses on creditors. That didn’t happen. However, the creditors have not gotten away without pain. The Federal Reserve is allocating some of the cost of restructuring to creditors in the form of financial repression. By holding interest rates at very low levels, debtors can more easily refinance their debt, which is a form of credit restructuring. Creditors are also being forced to fund lesser quality debt in the desperate search for yield.

The missing element of financial repression has been the lack of inflation. Central banks seem to remain under the sway of monetarism, which postulates that the central bank can create any inflation it wants by expanding its balance sheet. This has proven to be untrue. In our opinion, inflation comes from the intersection of aggregate supply and aggregate demand and the aggregate supply curve is nearly horizontal in a globalized and deregulated world, meaning that rising demand won’t necessarily lead to higher price levels. Without rising inflation, it is hard to enforce financial repression in a manner that would rapidly address the debt overhang. Think of the above chart, which is a ratio of debt and GDP; rising inflation would lift nominal GDP (the denominator) and consequently lower the ratio, if debt merely stays the same. The fastest way to lift nominal GDP is with higher price levels.

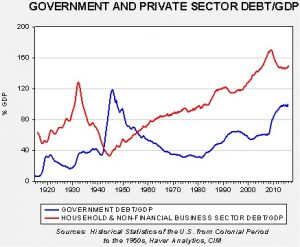

Needless to say, this solution isn’t making either side very happy. It is worth noting that when we had this problem in the 1930s the solution was WWII. The government acted as the third party, taking on massive debt via war spending which allowed the private sector (households and businesses) to effect a debt swap, shifting their debt to the government. The chart below shows how that worked.

In the most recent debt cycle, we have seen a smaller version of the post-1930 debt swap but, frankly, the government didn’t increase debt enough. Political constraints prevented that from occurring. Consequently, the swap was never fully executed and now, with increased business borrowing, progress on deleveraging has stalled prematurely.

So, what is the answer? There are really two paths to take. The first is to take another swing at expanding government debt through fiscal spending. Although there is a rising drumbeat for such policies, they are only attractive in the abstract. Politically, you have to pick winners and losers if fiscal spending is going to expand. Given the degree of political gridlock, it has been virtually impossible to come up with mutually agreeable spending. The other path would be to bring inflation by reversing globalization and deregulation, the policies of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. In the end, neither choice is particularly attractive, so we continue to muddle through with slow growth and low inflation. Until there is some political resolution of this issue, we expect more of the same.