Daily Comment (January 3, 2019)

by Bill O’Grady and Thomas Wash

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] It was all about Apple (AAPL, 157.92), which is down around 8% in the pre-market trade, and the yen. Here is what’s going on:

AAPL: Apple[1] released a letter warning investors that the company would miss revenue estimates. Two reasons were given for the decline, weaker economic growth in China and disappointing upgrades. We won’t discuss the latter issue but the former is important. The trade conflict between the U.S. and China hit the Middle Kingdom at an inopportune time, just as China was trying (again!) to implement deleveraging. The act of reducing debt growth would, on its own, slow growth and cutting exports to the U.S. added to that issue. To some extent, the slowdown in Chinese growth isn’t a surprise; recent purchasing managers’ data already showed that the Chinese economy was slowing. However, the AAPL news suggests the trade war may be affecting U.S. equity earnings. There are already rising worries about 2019 earnings due to slowing economic growth. For a prominent company like Apple to confirm these concerns has led to a sharp decline in U.S. equity futures this morning.

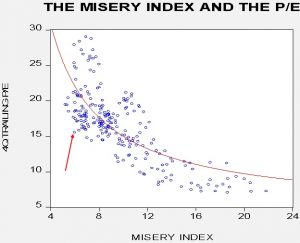

At the same time, as our P/E chart at the end of this report shows, much of this worry has probably already been discounted. The multiple has declined significantly and is unusually low given the level of economic activity.

This chart is a scatterplot of the four-quarter trailing P/E and the misery index, the sum of the unemployment rate and the yearly change in inflation. The arrow shows the current ordered pair of these variables. Essentially, this ordered pair usually indicates either a P/E in the low 20x or a misery index in the neighborhood of 10 (e.g., 6% unemployment with 4% inflation) instead of the current 5.9. Obviously, markets are forward-looking but this data suggests that the financial markets are discounting a plethora of economic weakness. So, to some extent, the Apple news should be seen as a confirmation rather than a new insight.

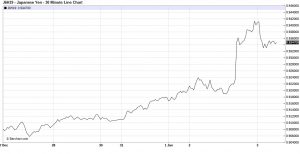

The yen: Overnight, the JPY soared in value.

This is a five-day chart of the yen futures (which are priced at 100 JPY per dollar). In cash terms, the yen jumped to 105. There is a lot of speculation about why this occurred,[2] ranging from an algorithm-driven event to perhaps related to the Apple news. The JPY is seen as a safety asset and if fear of a global recession is increasing then it makes sense that the JPY would rally. We note the AUD fell hard, which would tend to confirm the China story. We have been favorable to the yen for some time; on a purchasing power parity basis, the currency should be trading around 60 yen to the dollar. Because Japan has been a persistent current account surplus nation, it is forced to invest overseas. However, if Japanese domestic savers become fearful, they tend to repatriate, leading to a stronger yen. That happened last night, although some of it was likely exacerbated due to thin trading conditions. Still, the rise in the JPY is a warning that concerns are elevated.

Paygo: “Pay as you go” is a budget policy that requires the government to make all discretionary actions budget-neutral. Thus, if taxes are cut, spending must fall to offset the action. This is why there are discussions about “dynamic vs. static scoring” for budget actions. Supply side economists will argue that tax cuts stimulate the economy and boost revenue so the potential loss of revenue from a well-structured tax cut is less than the mere revenue loss measured with a static score. In its most extreme form, tax cuts are thought to not only be revenue-neutral but perhaps even revenue-increasing.

President G.H.W. Bush implemented this policy. It was a statutory requirement from 1990 to 2002. His son allowed the measure to expire which permitted the 2003 tax cuts and the Medicare prescription drug expansion to be enacted. Both widened the deficit. After taking back the House, the Democrats made Paygo the House rule from 2007 to 2010. However, in reality, the Paygo rules had loopholes for emergency spending and the like. Still, they acted as a brake on spending and revenue adjustments.

There is a major battle brewing between the Left-Wing Establishment (LWE) and Left-Wing Populists (LWP) on this issue.[3] Incoming speaker Pelosi wants to return to Paygo; her progressive wing opposes her on this measure. The LWE wants to be the responsible “adults in the room” and use Paygo to restrain the spending measures from the LWP and further tax cuts and extensions from the GOP. The LWP sees Paygo as an unnecessary restraint on environmental and social spending.

On its face, this is just a run of the mill fight over spending priorities. However, there is something much more important underlying this fight. The person to watch here is Stephanie Kelton, an economics professor at Stony Brook. Kelton is rapidly becoming the face of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a heterodox theory on money and the economy. She spent 17 years at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) in the economics department and was the chair during her tenure. UMKC is the center for MMT with some of its seminal thinkers on the faculty. She was also the chief economist for the Senate Budget Committee and senior economic advisor to the Sanders campaign.[4]

We will have more to say about MMT later this year but, in a nutshell, the theory suggests that the government is the primary issuer of currency. We use and trust our currency because it is necessary to pay taxes. Taxes are designed, like monetary policy, to manage the economy. Taxes are not required to fund the government; the government can fund itself at any level simply by issuing currency. Instead, taxes, like interest rates, should be adjusted to constrain inflation and for other social goals. So, a deficit isn’t bad but normal, and should only be reduced when the economy is overheating. As long as slack exists in the economy and there are needs in society, the government should simply spend the money until inflation becomes a problem.

There are some caveats. First, these rules only apply to governments that issue fiat currencies and borrow in their own currencies. So, state and local governments, which don’t issue their own currency to pay for stuff or service their debt, cannot run deficits. Thus, nations under a gold standard or nations with fixed exchange rates can’t use MMT. For example, the Eurozone nations cannot use MMT (as the Greeks discovered) because they don’t borrow in a currency they issue. Second, in practical terms, it is really hard for citizens to believe that their taxes aren’t necessary to fund the government. If they are not necessary, why pay them? Even if MMT is correct, the belief that taxes fund the government (which is true on a state and local level) may be a useful fiction.

However, during periods of economic stress, the government should run deficits but needs a theory that becomes the narrative to defend and explain the deficits. During the Great Depression, Keynes offered that narrative. In the early 1980s, when the U.S. was trying to quell inflation through high real interest rates, deregulation and globalization, there was a need for deficits to act as a safety valve for the economy. Supply side economics offered that narrative. Kelton’s MMT could very well be the theory that becomes the LWP’s narrative to explain how we can provide free college and health care to all without raising taxes to pay for it. Another thought is that high marginal tax rates are not necessary to fund the government but they can act to change the behavior of business leaders. If high salaries are mostly taxed away, CEO pay no longer acts as a “scorecard” for success and firms may be inclined to pay their workers more.

Our position has been, for some time, that the level of inequality in the U.S. was unsustainable and that a cycle of equality was coming. But, for that cycle to develop, a narrative is necessary; MMT will likely be that narrative. The key area to watch is the forex market. If the LWP is victorious and deficits soar, the exchange rate market will become the arena for how markets adjust. The first nation to go MMT will likely also have a weaker currency. In fact, the exchange rate may become the only constraint on deficits. As the past four decades have shown, a nation open to trade and technology disruption (which are not necessarily separable) can keep inflation under control. But, a decline in the currency might act as a constraint. Perhaps, under MMT, we could end up with something resembling a loose gold standard. However, this assumes that some nation doesn’t adopt MMT and become the standard bearer, much like gold did.

So, this fight is a big deal. If Pelosi loses it, watch Kelton and MMT. It could become the new narrative for the equality cycle.

Oil: OPEC output is declining[5] and there are growing worries that U.S. production cannot be maintained[6] without rising investment, which is unlikely with tighter financial conditions and low oil prices. Our position is that oil prices are well below fair value. We would look for a recovery in the coming months.

[1] https://www.ft.com/content/433fd028-0ed6-11e9-a3aa-118c761d2745?emailId=5c2db165ed6949000407cf16&segmentId=22011ee7-896a-8c4c-22a0-7603348b7f22

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-02/yen-surge-algos-set-off-flash-crash-moves-in-currency-market

[3] https://www.politico.com/story/2019/01/02/house-democrats-feuding-1077467

[4] https://stephaniekelton.com/2013/06/28/biography-2/

[5] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-02/opec-output-falls-most-in-almost-two-years-as-saudis-begin-cuts

[6] https://www.wsj.com/articles/frackings-secret-problemoil-wells-arent-producing-as-much-as-forecast-11546450162