Daily Comment (July 27, 2016)

by Bill O’Grady and Kaisa Stucke

[Posted: 9:30 AM EDT] The FOMC meeting concludes today. Expectations are very low for this meeting although we would not be surprised to see the statement take on a more hawkish tone. Markets are not expecting the FOMC to move higher this year; in fact, the fed funds futures don’t signal a greater than 50% probability until February of next year. It should be noted that this projection has been creeping in recently. Just a few days ago, we didn’t get the first greater than 50% month until June. Still, the markets are consistently not expecting a rate hike this year. We would not be surprised to see the Fed try to inject some degree of uncertainty into this calculation but we doubt they will have much success.

PM Abe unveiled a massive fiscal stimulus plan, which came in at ¥28 trillion ($265.3 bn). Early estimates were around ¥20 trillion, so this is a big deal, representing about 6% of GDP. Of the ¥28 trillion, it appears that ¥13 trillion is new spending and the rest is loan guarantees. The details of the package will be released sometime next week but it does appear that this spending will be spread out over several years, which will dampen the impact of the fiscal package. We do note that the JPY weakened overnight and the Nikkei rose on the news. The headline data is quite bullish but the overall impact will probably be less than meets the eye. Still, it is a positive step for policy in Japan as monetary policy is clearly near the end of its usefulness. On this topic, the WSJ is reporting that Japan is considering issuing 50-year bonds. It is possible that a 50-year bond can be a tool in “stealth” helicopter money. The Abe government is probably reluctant to openly implement Monetary Funded Fiscal Spending (MFFS) because of its bearish effects on the JPY—it doesn’t want to trigger a currency war. In MFFS, the fiscal authority spends money and issues bonds that the central bank buys and effectively extinguishes by holding them to maturity. Given the usual adult lifespan, a 50-year bond is essentially a lifetime, thus allowing the fiction that MFFS isn’t being done when, essentially, it is. It should be noted that France and Spain have issued 50-year bonds and Ireland and Belgium have issued century bonds.

There has been some curious behavior in the LIBOR markets recently. Although expectations of Fed tightening are benign, LIBOR rates have been ticking up.

This chart shows 3-month USD LIBOR. Note that over the past month, the rate has moved up around 10 bps. Usually, such moves occur for one of the following reasons: (a) the Fed is raising rates or (b) there is a systematic financial system problem developing, leading investors to flee the LIBOR market for sovereigns. The second case is one of the reasons for monitoring the TED (T-bills vs. Eurodollar) spreads.

The TED spread has ticked up modestly, but isn’t signaling a problem.

Just compare the above chart to the long-term TED.

Note how LIBOR rates spiked in 2008 and was “spikey” from mid-2007 through 2008. That is a more classic example of the flight to safety element of the TED spread. We are not seeing that now.

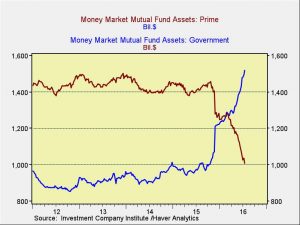

So, why the rise in rates? It’s entirely due to regulation. On October 14, prime money market funds (MMF) will see their statutory maximum weighted average maturity fall from 90 to 60 days. In addition, institutional MMFs will be forced to institute a floating NAV and can put up “gates” to slow withdrawals during crises. We are already seeing the impact.

Total Prime MMFs have declined about $500 bn and government funds have risen by about the same amount. Prime MMFs now represent 37% of total MMFs, down from 53% last October. The total assets in MMFs are about the same but the allocation has shifted from Prime to government MMF, which don’t face the same restrictions. We expect further shifts as investors begin to realize that a Prime MMF isn’t “cash.”

Here are some potential market effects:

The dollar could rise. The rise in USD LIBOR hasn’t been matched by a similar rise in EUR LIBOR. All else held equal, the higher yield should support dollar buying.

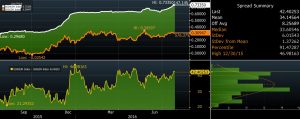

This chart shows USD and EUR 3-month LIBOR, with the spread on the lower chart. Note how the spread has widened recently.

Commercial paper markets will be adversely affected. Prime MMFs buy commercial paper. As funds shift to government funds, the money available to buy commercial paper will decline, boosting funding costs to commercial paper issuers.

A secular change in the TED spread is likely. In general, investors discount the odds of a problem in the financial markets when they buy LIBOR-based paper. With the rules on Prime MMFs changing, the risk calculation will change which should permanently shift the spread wider. It is important for investors to realize that the TED isn’t necessarily signaling a financial system problem during this reset.

The rise in LIBOR and the dollar could be a bearish factor for commodities. If the regulatory change acts as a de facto monetary policy tightening and isn’t offset by the Fed, we may see some weakness develop in commodities. The primary driver of this will be the dollar.

Overall, investors will need to consult with their MMF providers to determine if they are willing to stay with Prime MMFs or shift to government MMFs. The issue really is what the function of the MMF is in the portfolio; if it is truly cash, then the government funds are more appropriate. If it is for yield, then one needs to realize that a Prime MMF will likely lose its cash-like characteristics during financial crises and one could find that there will be a delay in tapping a Prime MMF if financial conditions deteriorate. In addition, the floating NAV could mean that “a dollar isn’t a dollar” under some conditions. In other words, the new regulations force the Prime MMFs to “break the buck” if asset values decline.