Tag: Canadian home prices

Asset Allocation Weekly (May 14, 2021)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

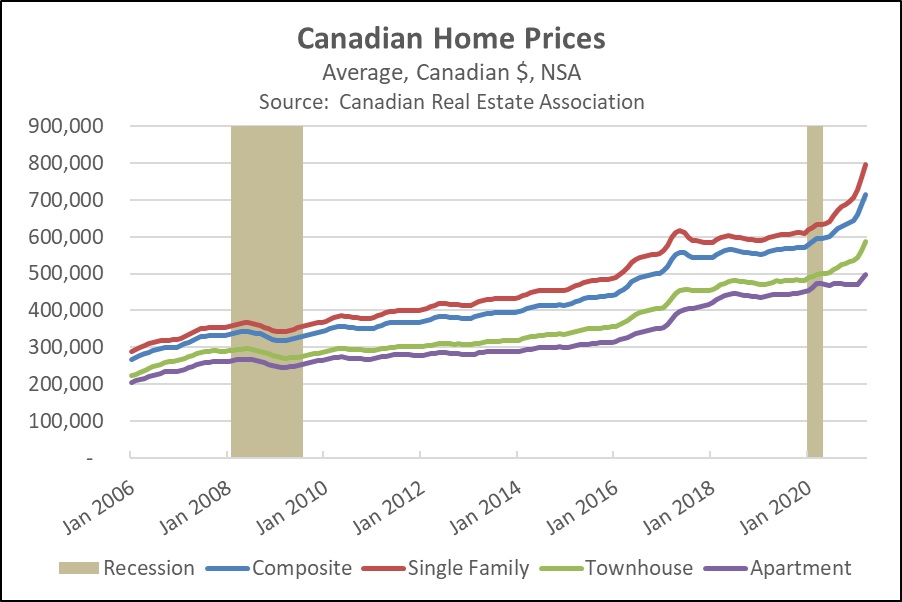

Since the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 (GFC), any rapid rise in home prices has tended to spark fears of another bubble bursting. U.S. home prices have recently been up more than 10% from one year earlier, marking their strongest gains since the recovery period right after the GFC. However, those gains have been overshadowed by the even bigger increases in Canada. Home prices north of the border rose 13% in the year ended December 2020, and they were up an even stronger 20.1% in the 12 months ended March 2021 (see chart). Does that mean the Canadian housing market is in a bubble? What’s the risk that Canadian home prices will crash back to earth, dragging down the financial system and Canadian stocks?

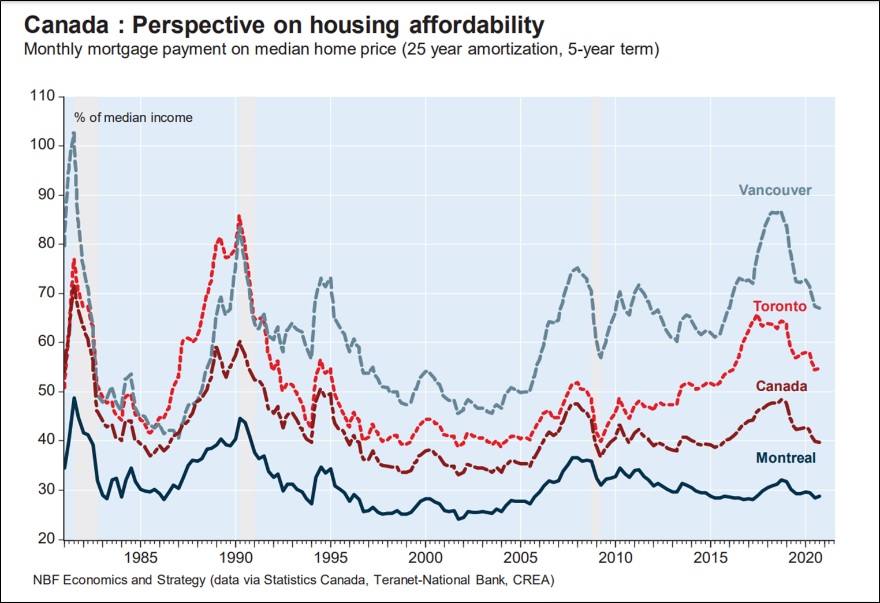

One reassuring sign is that Canadian homes are still affordable despite the recent price surge. Based on today’s median home price, mortgage interest rates, and typical Canadian mortgage terms, a homebuyer’s monthly mortgage payment would equal only about 40% of the country’s median income. As shown in the following chart, that’s similar to the level seen during most of the last decade. It’s also much lower than in the 1980s and 1990s. Naturally, housing costs can be much higher in major metropolitan areas. However, even in those locales, affordability has improved over the last few years. That’s because the recent price hikes have been largely offset by falling interest rates and rising incomes. Between 2017 and 2019, price gains were also held in check by tightened regulations, like a new tax on foreigners buying property in Vancouver and Toronto and “stress test” rules requiring loan applicants nationwide to show they could afford their mortgage even if interest rates were 2% higher than when they applied. Current affordability levels suggest Canadian home sellers can still find plenty of buyers.

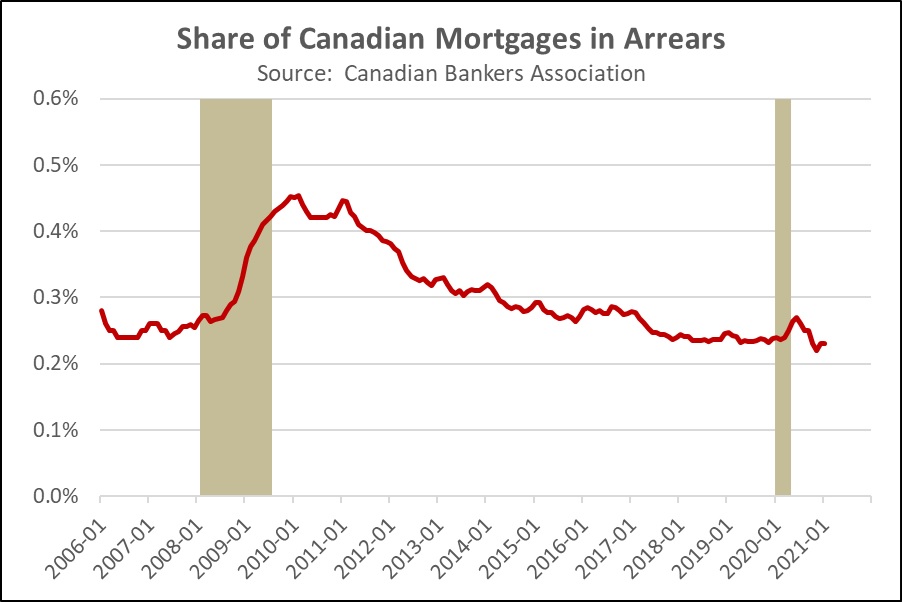

Finally, it’s important to remember that Canadian bank regulations and mortgage terms are much more conservative than in the U.S. The typical Canadian mortgage payment is calculated based on an amortization period of 25 years, and the loan matures in five years, with steep penalties for early refinancing. Long-term homeowners in Canada expect to roll over their mortgage on a strict five-year schedule. Even when homeowners sell their property to buy another, the outstanding balance on the original mortgage is usually applied to the new house. This system helps protect Canadian banks from falling interest rates. In addition, the new stress tests help ensure that borrowers are good credit risks, while government rules discourage banks from selling or securitizing their mortgage loans. The Canadian system therefore tends to keep lenders and homeowners “married” for extended periods, which appears to improve underwriting standards. As evidence of that, the chart below shows that there has been no discernable rise in Canada’s mortgage delinquencies. Canadian mortgage delinquencies remain just a fraction of U.S. delinquencies, despite the recent jump in home prices and increased mortgage debt.

In sum, it appears that the Canadian housing market is responding to the same kinds of pandemic-driven trends facing the U.S. market. Increased desire for personal space, falling mortgage rates, and ample savings have boosted housing demand, even as job fears or health concerns have limited new listings. The boom in Canadian home prices simply doesn’t seem to reflect loose mortgage standards or irresponsible lending, so we are not currently concerned about a housing bubble bursting or causing widespread financial problems north of the border.