Tag: europe

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Mid-Year Geopolitical Outlook: Searching for the Endgames (July 14, 2025)

by the Confluence Macroeconomic Team | PDF

As the first half of 2025 draws to a close, we typically update our geopolitical outlook for the remainder of the year. This report is less a series of predictions as it is a list of potential geopolitical issues that we believe will dominate the international landscape for the rest of 2025. The report is not designed to be exhaustive. Rather, it focuses on the “big picture” conditions that we think will affect policy and markets going forward. Our issues are listed in order of importance.

Issue #1: US-China Tensions Remain

Issue #2: Russian-Ukraine War Continues

Issue #3: Fallout From Israel-Iran War

Issue #4: US Mulls Capital Controls

Issue #5: Prospects for Lasting Economic Change in Europe

Issue #6: AI Investing Gets Second Wind

The podcast episode for this particular edition will be posted under the Confluence of Ideas series later in the week.

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #69 “Introducing Friedrich Merz, Chancellor of Germany” (Posted 6/23/25)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Introducing Friedrich Merz, Chancellor of Germany (June 23, 2025)

by Daniel Ortwerth, CFA | PDF

The last year has witnessed an extraordinary series of events in German politics. A chancellor failed a no-confidence vote. A parliament collapsed. The subsequent parliamentary election, which typically happens on a five-year cycle, was moved forward by five months. In that election, Germany’s far-right party surged to a second-place finish, capitalizing on recent successes on the regional level. For the first time since World War II, a nominated new chancellor failed to receive the necessary majority in the first round of voting and required a second round to ascend to the position. Emerging from this political turbulence, we find the new chancellor of Germany, Friedrich Merz, whose background and policies now serve as a lens to better understand the largest country in Europe and third largest economy in the world.

This report begins with a brief biography of Chancellor Merz, focusing on his political career. It continues with a discussion of the political context of today’s Germany that gave rise to his election, and it culminates with considerations of what we should expect from his leadership. As always, we conclude with implications for investors.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – From Magnificent 7 to European Revival (April 14, 2025)

by Thomas Wash | PDF

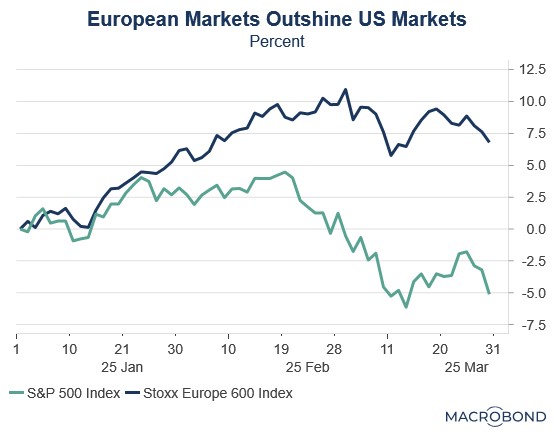

European equities have long suffered from investor skepticism and been burdened by perceptions of excessive regulation, bureaucratic inertia, and elevated operating costs. These structural challenges have historically overshadowed the region’s fundamental strengths. Yet 2025 has marked a striking reversal, with European stocks delivering exceptional returns that have handily surpassed US market performance.

Much of Europe’s recent outperformance relative to the US can be traced to the unwinding of the “Trump trade,” which began in the weeks following Donald Trump’s victory in the November 2024 election. During this time, markets seemed to embrace the narrative that his policies — deep tax cuts, aggressive deregulation, and a pro-growth agenda — would cement US economic dominance. While tariffs were always a part of the equation, investors initially expected them to be used selectively rather than aggressively.

While US equities surged after the November election, European stocks languished as investors anticipated a widening growth divide. The eurozone has now gone seven consecutive quarters without achieving 2% annualized growth in its gross domestic product, a streak dating back to the third quarter of 2022. Nowhere were these struggles more apparent than in Germany, where the industrial sector — traditionally the Continent’s economic powerhouse — became its biggest drag.

Market expectations shifted abruptly in the Trump administration’s early weeks as it simultaneously challenged existing trade arrangements and demanded greater military spending from allies. The tariff threats created immediate uncertainty as businesses shelved investment plans and consumers braced for inflationary pressures. Meanwhile, growing doubts about US security commitments prompted EU leaders to accelerate plans for strategic autonomy.

We think the rotation from US to European equities was primarily valuation-driven, with the US’s once-dominant Magnificent 7 declining as investors shifted from growth to value. This marked a dramatic reversal from previous years when tech-heavy growth stocks consistently outperformed. European markets, with their heavier weighting in value sectors and more attractive price-to-earnings ratios, became natural beneficiaries of this change in investor preference.

While capital rotation remains modest to date, escalating trade tensions may accelerate foreign divestment from US assets in favor of European markets. These geopolitical strains have triggered a broad risk-off shift among investors, with capital flowing toward value assets rather than growth equities. This reallocation reflects a fundamental reassessment of global trade dynamics as nations increasingly recognize that traditional US trade relationships may be changing for good.

This shifting sentiment marks a potential inflection point after years of sustained US equity outperformance. For decades, global investors have disproportionately favored US markets, having been lured by three key advantages: (1) superior growth prospects, particularly in the technology sector; (2) unrivaled market depth and liquidity; and (3) the structural strength of the dollar. These factors became particularly pronounced in the post-pandemic era when the greenback’s appreciation created an additional return tailwind for foreign investors.

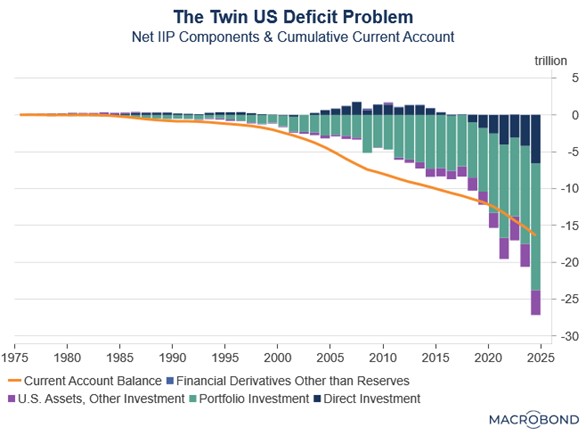

In an especially important development during this period, the US began running deficits in both its trade balance and its “primary income” balance. This twin deficit was problematic because it signaled that foreign investors were earning higher returns on their US investments than what US residents were earning abroad. In other words, the US was not only importing more than it exported but also paying out more in interest and dividends to the rest of the world than it was receiving.

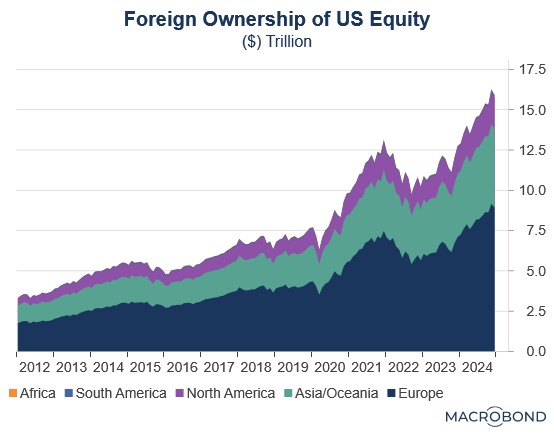

The growing imbalance stemmed from two key factors: persistent US equity outperformance relative to global markets and the Fed’s rate hikes that made Treasurys more attractive to foreign investors. These forces converged in the Net International Investment Position, resulting in the value of foreign-held US assets eclipsing America’s cumulative trade deficit for the first time ever. The shift reflected both a reversal from direct investment surplus to deficit and rising portfolio investment values — twin manifestations of superior US asset returns.

Typically, such conditions would prove problematic for most economies as they could trigger disproportionate currency outflows and subsequent depreciation or make its markets vulnerable to panics. However, the US dollar’s unique status as the global reserve currency and its deep and open capital markets have largely shielded it from these adverse effects.

Nevertheless, significant risks remain. US equity markets could experience heightened volatility should foreign investor sentiment deteriorate, with the technology sector being particularly vulnerable due to its elevated valuations. The scale of this exposure is evident in foreign holdings, which now compose over 30% of US equities, driven by a dramatic surge in both portfolio income and direct investment flows.

A sudden erosion of confidence in US equities could precipitate a significant capital rotation into foreign equities and gold. Europe appears particularly well-positioned to benefit from this shift, owing to its relative valuation discount and potential for capital repatriation flows. Within the region, Germany stands out as especially attractive given its increased defense spending commitments. Meanwhile, gold could emerge as the safe-haven asset of choice, with the potential to displace US Treasurys as a reserve asset over time.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #138 “From Magnificent 7 to European Revival” (Posted 4/14/25)

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Growing Fragility in the US Bloc (April 7, 2025)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

We at Confluence have written extensively on the end of post-Cold War globalization and the fracturing of the world into various geopolitical and economic blocs. We’ve noted that the large, rich bloc led by the United States is an attractive place for investors, but fractured supply chains and rising international tensions may produce a range of economic and financial market problems, from elevated consumer price inflation to higher and more volatile interest rates. In this report, we explore what could happen to the US bloc as President Trump pursues his aggressive policies to push the costs of Western security and prosperity onto the US’s traditional allies. As we’ve noted before, those policies run the risk of reducing US influence with its allies and undermining cohesion within the US bloc. We assess in this report that reduced cohesion probably won’t splinter the US bloc in the near term. Nevertheless, we begin laying out how the world could change if the US bloc does disintegrate, and we discuss the economic and market implications if it does.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Podcast – #64 “Growing Fragility in the US Bloc” (Posted 4/7/25)

Weekly Geopolitical Report – AUKUS (October 11, 2021)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

On September 15, the leaders of the U.S., U.K., and Australia announced a new security relationship which includes a nuclear submarine arrangement with Australia. Although it will likely take a couple of decades before Australia will have its own indigenous nuclear propulsion vessels, the treaty means that the U.S. and U.K. will likely begin sharing nuclear technology and other weapons systems.

The announcement not only marked the beginning of a new security relationship in Asia for the U.S. and U.K., but it also marked the end of another one, a $60 billion defense arrangement that France had with Canberra. France had previously agreed to provide Australia with diesel/battery submarines, but this new deal scuttled the French arrangement. The French were incensed; ambassadors were recalled, and European governments denounced the new arrangement.

It is not a huge surprise that the French were upset, but the degree of the reaction seemed strong given the violation. Diesel submarines pale in comparison to the capabilities of nuclear propulsion. The former is only useful in coastal protection. They need to resurface to use the diesel engines to recharge batteries; during this period, they are vulnerable to attack. They also require regular refueling. Nuclear submarines don’t need to resurface and can extend their patrol range significantly compared to a diesel-powered vessel. When the deal was made in 2016, diesel subs may have been adequate for the risks Australia perceived. That is no longer the case. So, it should have come as no surprise that Australia would consider an upgrade. Although France has nuclear propulsion technology, it is not as effective as American technology.

The U.S. decision to create this new security arrangement, Australia’s acceptance, the U.K. decision to join, and the reaction of France all reflect an evolving geopolitical situation in Asia. In this report, we will discuss why the three nations decided to create a new pact. From there, we will offer a short geopolitical analysis of Europe, followed by an examination of the French and European reactions. We will close with market ramifications.