Tag: foreign policy

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – The US Presidential Election: Foreign Policy Implications (October 7, 2024)

by Daniel Ortwerth, CFA and Thomas Wash | PDF

History shows that, despite the promises made as candidates, United States presidents display remarkable foreign policy consistency from one administration to the next. While often distinguishing themselves in the realm of domestic policy, the imperatives of national security tend to force the hands of presidents into choices that change very little (if at all) with party affiliation. In other words, foreign policy tends to be remarkably consistent.

Nevertheless, foreign policy typically provides at least some room for maneuver, and presidents use this wiggle room to pursue their priorities as circumstances permit. Often these priorities are different from one candidate to the next. With the presidential election looming in November, we need to understand these differences and their investment implications.

This report analyzes how US foreign policy might look in a new term for former President Donald Trump, the Republican candidate, and in an initial term for Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic candidate. It begins with a characterization of the two candidates according to the main American foreign policy traditions. It considers the kinds of cabinet members they will probably choose to fill the rosters of their foreign policy teams, and it culminates with a review of their priorities as we know them. As always, we conclude the report with implications for investors, in this case as they differ between the two candidates.

Don’t miss our accompanying podcasts, available on our website and most podcast platforms: Apple | Spotify

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – The Recent Iranian Election: Results & Implications (August 19, 2024)

by Daniel Ortwerth, CFA | PDF

The Iranian political landscape experienced a major earthquake on May 19, when the country’s president, Ebrahim Raisi, died in a helicopter crash on his return from a visit to neighboring Azerbaijan. Consequently, in June and July, Iran conducted a two-round presidential election with a surprising result. In a country ruled by a highly conservative theocracy, whose political system has become increasingly dominated by its most hardline, right-wing parties, a reformist (i.e., moderate) candidate came out on top. How did this happen, and what does it mean for the rest of the world? Will it inspire changes in Iranian domestic politics or foreign policy? How will it affect the United States, and what does it mean for investors? Since Iran tends to be a disruptive force in the world, these and other questions need our attention.

This report begins with a review of three key challenges currently facing Iran: regional and global opposition to Iran’s long-term geopolitical strategy, deepening economic woes, and an upsurge in societal unrest. We continue with an explanation of the role of the president in the Iranian political structure and a brief introduction to the winner of the election, reformist Masoud Pezeshkian. We conclude with an explanation of why we do not expect this change of leadership to shift Iran’s geopolitical strategy, even if it does usher in adjustments to how it approaches its key challenges. As always, we conclude with implications for investors.

Note: There will be no accompanying podcast for this report.

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – The US Geopolitical and Economic Bloc as an Investment Region (August 5, 2024)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

More than a decade ago, we at Confluence began describing how United States voters have become more reluctant to shoulder the costs of global hegemony. We’ve shown how increased populist isolationism in the US and other Western nations helped embolden Chinese General Secretary Xi, Russian President Putin, and other revisionist authoritarians to become more assertive in their efforts to undermine the US-led world order. As the resulting geopolitical tensions prompted leaders around the world to seek military, economic, and cultural allies to preserve their security and prosperity, we noted a clear fracturing of the world into relatively separate geopolitical and economic groups or “blocs.” We think this global fracturing is bound to have big implications for investors.

To better understand the new blocs and gauge how they might impact investors, we developed an objective, quantitative method to predict which bloc a country would adhere to in the coming years. We first published our findings in our Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report from May 9, 2022. In our report today, we update the analysis. We will also do a deep dive into the attractiveness of the US bloc as an investment region, the prospects for the bloc staying together after the US elections in November, and the implications for investment strategy.

Note: There will be no accompanying podcast for this report.

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #122 “A New Factor for Gold Prices” (Posted 7/15/24)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – A New Factor for Gold Prices (July 15, 2024)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

The standard regression model is as follows:

Y = α +β(X) + ε

Where Y is the dependent variable, X is the independent variable, α is the intercept, β is slope and ε is the error term. No model, no matter how many independent variables are added, can capture the complete relationship to the dependent variable. However, a well-constructed model will account for most of the variation in the behavior of the dependent variable.

Although it tends to get short shrift in statistics classes, the error term is rather interesting, especially with regard to time series models. Essentially, the error term, or epsilon, is where the unspecified causal factors that affect the dependent variable are housed. The goal of modeling is to select the most meaningful independent variables and then assume the ones that are not specified are not important enough to dramatically affect the dependent variable. It may be that the unspecified terms are not all that important, or if they are, they are offset by other unspecified variables so that the model’s performance isn’t adversely affected.

Sometimes, a dependent variable begins to exhibit deviations to the model’s estimate; this may be caused by several factors. One is that the relationship between an already specified independent variable and the dependent variable has changed. The relationship may have rested on some other factor, such as policy, that has made it more or less important. Over time, the β, or the correlation coefficient, will adjust to this new relationship. In other cases, a previously unimportant variable, contained in epsilon, becomes important.

We think this latter situation is affecting the gold market.

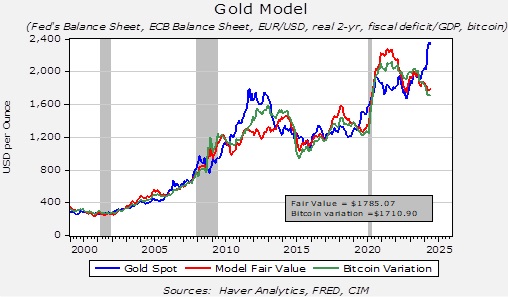

The chart above is our basic gold price model. As the chart shows, the model’s estimation occasionally deviates from the actual price. If nothing has changed, this deviation may suggest an over or undervalued market. The recent spike in gold prices is clearly running well above our model’s estimation. However, we think we have isolated a change that accounts for this deviation.

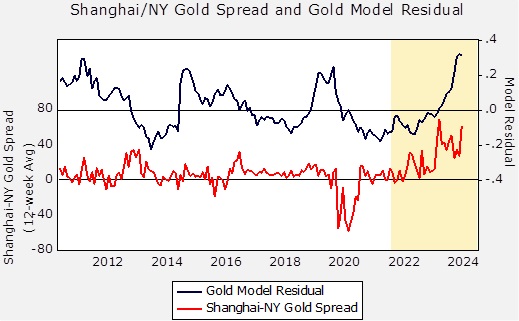

The upper line on the above chart shows the model’s residuals since 2012. The lower line shows the spread between gold prices in Shanghai and New York. The history of this spread shows some deviation, but in general, this condition invites arbitrage if prices are higher or lower in one market compared to the other. Note that the New York prices far exceeded those in Shanghai during the pandemic. We can assume the mechanisms for arbitraging that market were disrupted by the pandemic, and the spread narrowed when these mechanisms returned. The area on the chart above in yellow indicates the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Note that gold prices in Shanghai have been persistently elevated relative to those of New York.

The G-7 implemented sanctions on Russia in the wake of the invasion, and perhaps the most draconian of those was the move to freeze Russian foreign reserves. This move raised fears in other nations that if they were to see relations with the US deteriorate, then similar actions might be deployed against them as well. So, in response, foreign governments have been increasing their gold purchases. Since the Chinese are concerned about the vulnerability of their massive US Treasury holdings, it appears they have been aggressively buying gold to the point where the Shanghai price has been persistently above the New York price.

It’s still too early to determine what impact this spread relationship will have on the overall gold price in the future, but this situation is a good example of when a previously quiescent variable, well contained in epsilon, suddenly becomes important. Faced with a model that is deviating from its past performance, the challenge for the analyst is to determine the cause. We believe that Asian buying, both from central banks and private investors, is the cause in this case. This condition could mean that when traditional bullish conditions for gold return (e.g., lower interest rates, weaker dollar, central bank balance sheet expansion), the price of gold could move sharply higher, bolstered by this new factor — enhanced Asian buying.