by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

One of the debates within economics is whether consumption is driven by income or wealth. The outcome of this debate is important for policymakers; if the goal of policy is lifting or constraining growth, knowing which factor is more important to consumption is critical. For example, if the goal is lifting economic activity and incomes are more important to consumption, transfer payments and tax cuts to lower-income households would be effective. On the other hand, if the wealth effect[1] has a stronger impact, the same goal might be better achieved with capital gains tax cuts and interest rate reductions.

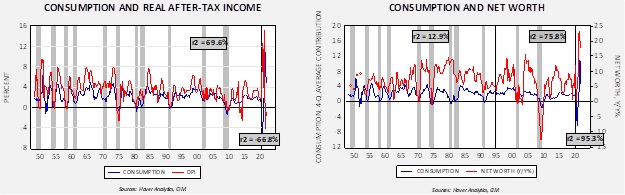

Until the mid-1990s, the evidence strongly suggested that income was much more important than the wealth effect. But, since the mid-1990s, consumption has been much more sensitive to net worth.

We measure consumption by the contribution to real GDP on a rolling four-quarter basis. Disposable real income is the yearly change to overall income on an inflation-adjusted basis on an after-tax basis. Net worth is the yearly change in assets less liabilities. From 1947 through 2019, the correlation between consumption and real disposable income was 69.6%. Comparing that to the impact of net worth, from 1947 through 1994, changes in net worth had only a modest positive impact on consumption; the two variables only were correlated by 12.9%. However, from 1995 through 2019, the correlation jumped to 75.8%.

Why did net worth become more important to consumption? We suspect there were at least two significant factors that changed the impact of the wealth effect. The first was the expansion of defined contribution pension plans. Households rarely saw the wealth they were accumulating under defined benefit plans. Only at retirement would they see what they would receive from their years of saving. Thus, rarely did they have knowledge of their accumulating wealth. But, under defined contribution plans, households could easily see the wealth they were accumulating. As a result of the bull markets in stocks and bonds in the 1990s, households felt “richer” and thus adjusted their spending to their expanding retirement accounts. Second, for most households, the largest asset they hold is their homes.

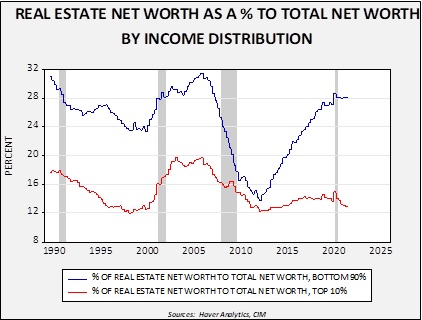

This chart shows real estate net worth compared to total net worth for the top 10% of households in the income distribution compared to the bottom 90%. Note that 90% of households have a much higher percentage of their net worth tied to residential real estate.

Until the mid-1980s, it was difficult to access the wealth in a home until the financial services industry made refinancing a simpler process. The ability to tap home equity is partly related to home prices. Although amortization will gradually increase the homeowner’s share of equity, immediate changes in home prices would have a bigger impact on the net worth from real estate. And, since in the early years of a mortgage most of a mortgage payment is applied to interest, weakening home values can have a detrimental impact on the wealth effect. Mortgage lending is leveraged; a “prudent” loan is 80% loan to value, so small changes in home prices can have outsized effects on the net worth of the bottom 90% of households.

Returning to the first chart, we have isolated the period after the pandemic. What is remarkable is that the relationship between real disposable income and consumption has become negative; this is likely a fluke, a function of a rapid increase in income in the form of transfer payments at a time when spending was limited due to the pandemic. As more goods and services became available, spending has recovered. Meanwhile, fewer transfer payments have led to falling real disposable income. This situation will eventually normalize but still suggests that, in the short run, policies that affect real disposable income may not have much impact on consumption. At the same time, the relationship between net worth and consumption has risen to 95.3%. This rise may represent the fact that the aforementioned savings found a home in the asset markets. This outcome, too, may be a decline to pre-pandemic levels, but we expect the relationship to remain strong.

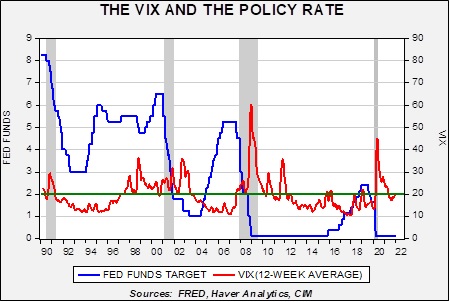

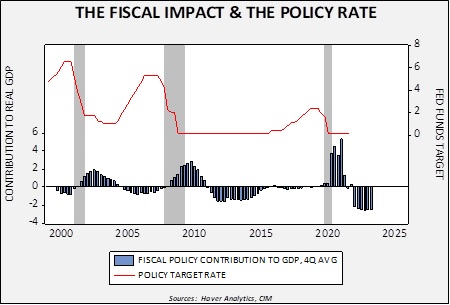

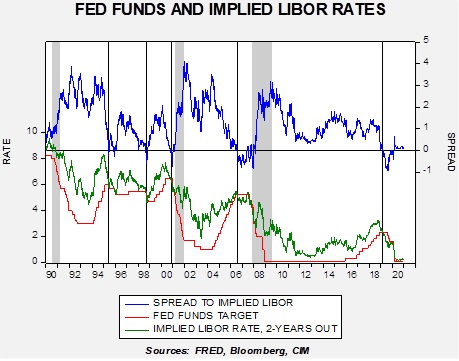

Although the current relationships between real disposable income, net worth, and consumption may be temporary, for now, we can only assume they will remain dominant. This means that policymakers face a potential risk as they move to tighten policy. If rising interest rates weaken asset markets, the impact on consumption could be stronger than expected. It might even lead investors to hold even more liquidity in part due to (a) fears of further declines in asset values and (b) due to the higher compensation for holding cash. Given that 90% of households will probably be more sensitive to home prices, actions that affect home values may have an unexpectedly large impact on economic behavior.

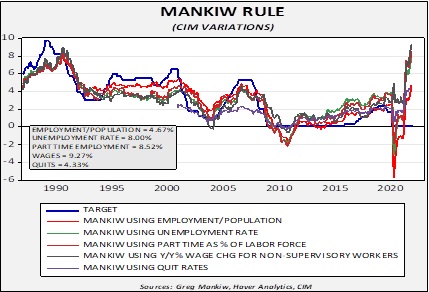

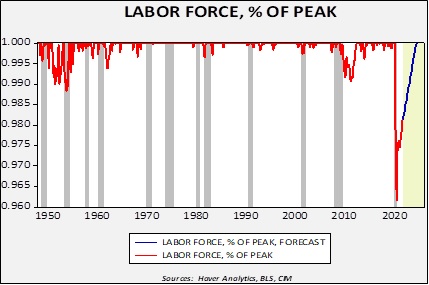

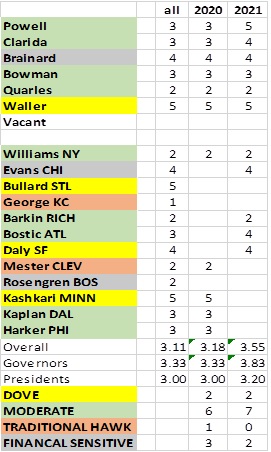

Although our outlook for 2022 assumed no rate hikes, comments from FOMC members suggest our position is probably wrong, and policy tightening is coming. We will be watching the path of home prices especially, but asset prices in general, to gauge the effects on consumption. Given the FOMC’s sensitivity to asset prices, weakness in housing prices or equities could cool the ardor to tighten policy.

[1] The wealth effect measures how much consumption is affected by changes in net worth.