Tag: Japan

Bi-Weekly Geopolitical Report – Meet Sanae Takaichi (November 10, 2025)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

In October 2025, Japan made history by electing its first female prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, a staunch conservative and protégé of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Her rise to power marks a significant shift in Japan’s political landscape, with implications for foreign affairs, domestic policy, and financial markets. As we show in this report, Takaichi’s administration promises a blend of hawkish national security, aggressive fiscal expansion, and economic revitalization, all underpinned by a nationalist ideology. As always, we wrap up the report with a discussion of the investment implications of her rise to power.

Note: The accompanying podcast for this report will be delayed until later this week.

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #73 “The Bank of Japan Cocks the Trigger” (Posted 4/18/22)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – The Bank of Japan Cocks the Trigger (April 18, 2022)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

In Hollywood movies, the classic device to convey a menacing threat is to have the tough-guy cop pull back the hammer on his revolver and cock the trigger. It’s not enough that the cop just points his gun at the criminal. Once you hear that “click,” you know the threat is imminent. You know it would only take a pull of the finger, and the bad guy is history. What you may not know is that Bank of Japan Governor Kuroda gave just this kind of “Are ya’ feeling lucky, punk?” performance last month. But as we discuss here, the big gun that Kuroda cocked was strictly financial—yield-curve control instead of a Smith & Wesson—and the opponent who got weak in the knees and fell to the ground wasn’t a petty thief, but the Japanese yen.

Since 2013, the BoJ has had an agreement with the government to work together on defeating deflation and bringing annual consumer price increases up to 2%. Shortly after Prime Minister Kishida’s election in 2021, the central bank renewed that commitment. The central bank’s effort initially focused on holding short-term interest rates very low and implementing massive asset purchases to pump funds into the economy. However, Japanese inflation remained stuck near 0%. In 2016, the BoJ, therefore, expanded its approach also to include “yield curve control,” in which it keeps short-term interest rates slightly negative (currently -0.1%) and commits to capping 10-year Japanese government bond yields at “around 0%.”

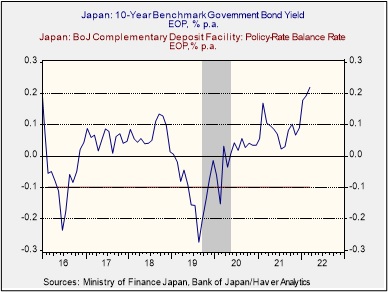

While the BoJ’s yield-curve control policy has been in place for six years, slow economic growth and low inflation around the world meant its commitment to hold long-term yields near 0% was never really tested. Even when the U.S. economy strengthened enough to prompt a series of Federal Reserve rate hikes from 2016 to 2018, the yield on 10-year JGBs only rose to about 0.1%, well within the range that seemed consistent with “around 0%” (see chart below). With 10-year JGB yields so well behaved, the BoJ’s yield-curve control policy seemed little more than an uncocked gun: concerning but not necessarily menacing.

The problem is that the global economic and financial landscape has changed dramatically over the last year. Galloping inflation in many countries outside of Japan has prompted central banks ranging from the Fed to the Bank of England to start hiking their benchmark interest rates. In fact, multiple Fed officials have signaled that their next move in early May might be an aggressive hike of 0.50% rather than the more usual hike of 0.25%. The policymakers’ scurry to hike rates has driven up government bond yields around the world, including in Japan. By late March, the 10-year JGB yield had jumped above 0.20% and was well on its way to 0.25%. Anything above that level would be hard to characterize as “around 0%,” so it was clear that the first real test of the BoJ’s yield-curve control policy had arrived.

And what did the BoJ do? At its March 18 policy meeting, it reiterated its commitment to buy whatever amount of JGBs necessary to keep the 10-year yield near 0%. In other words, it said that even if the other major central banks are hiking their interest rates to rein in inflation, it would buy an unlimited amount of government bonds to keep yields steady. So, it pulled back the hammer on its revolver and let the world hear an enormous financial “click.”

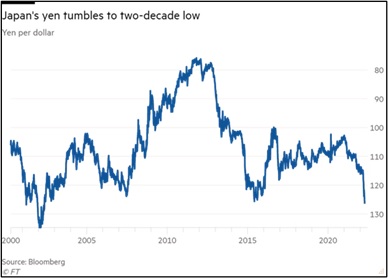

As shown in the chart below, the BoJ’s unexpected recommitment to loose policy has driven a series of considerable drops in the value of the yen. In late February, the currency fell to a seven-year low of 123.66 per dollar ($0.00809), down 6.9% from the end of 2021 and 16.6% from the end of 2020. What explains these gigantic declines? The BoJ’s promise to buy unlimited amounts of bonds and unleash unlimited funds into the economy equates to a threat of currency debasement. Essentially, it amounts to the threat of a limitless supply of money in the economy, with the result that the value of that money would be in question.

The implications of the BoJ’s stance are important for investment strategy. Given the historically high levels of debt weighing on major countries worldwide and growth challenges like falling birth rates, we think the Fed and other major central banks could also be tempted to adopt yield-curve control in the coming years. If their current efforts to fight inflation aren’t successful and longer-term bond yields start to drift higher, the central banks may decide they can’t afford to acquiesce. Like the BoJ, they could decide to sit on yields, implying that they would also have to be open to unlimited bond purchases and money creation. Currency values in those countries would be at risk. Many investors fearful about inflation would likely try to hedge their bets by purchasing physical stores of value such as gold, silver, and other commodities. This is a key reason we favor a significant exposure to such commodities in several of our asset allocation strategies. For those investors who don’t take steps to hedge against currency debasement, we would only ask, “Are ya feeling lucky?”

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Meet Yoshihide Suga (September 21, 2020)

by Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA | PDF

Because of Japan’s enormous role in the world, investors need to pay attention whenever the country undergoes a change of leadership as it did last week. After all, Japan currently accounts for some 7% of global stock market capitalization and 6% of the world’s gross domestic product. Not bad for a country whose 126 million people make up just 1.7% of the world’s population! Japan is also a key U.S. ally in the military and diplomatic spheres. It hosts huge U.S. military bases, allowing the U.S. to mount a robust “forward defense” in the Western Pacific, and it’s a vital partner in countering aggression from nations like China and North Korea. With its stable, vibrant democracy and dynamic consumer culture, Japan is a natural partner for the U.S. in East Asia.

But who is Japan’s new prime minister? In this report, we’ll sketch out the biography of Yoshihide Suga and examine how he’s likely to govern in the years ahead. We’ll focus especially on his probable policies in the areas of diplomacy, defense, economics, and finance, and we’ll discuss how effective he might be as a leader. As always, we’ll wrap up with a discussion of what the new prime minister might mean for investors.

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Rethinking China: Part II (August 3, 2020)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

In Part I, we described China’s situation using Japan as a historical analog. This week, we will complete the analogy and examine in some detail the potential motivations of Chinese and U.S. policymakers. As always, we will conclude the discussion with potential market ramifications.

China’s Situation

Similar to Japan in the 1930s, China has become a large economy showing geopolitical power that is threatening the established order. Similar to Japan in the 1980s, it has an economy overly reliant on investment, trade and debt. And, like Japan, it is dependent on sea lanes it does not control. Finally, as was the case with Japan during both the 1930s and 1980s, China has reached a point where the U.S. is refusing to accommodate its rise. However, unlike Japan, China is not as dependent on the U.S. for its security (although it is quite vulnerable to a blockade).

It is arguable that Deng realized China would eventually reach this state and thus encouraged Chinese leaders to bide their time. Simply put, Deng wanted to extend China’s ability to stay “under the radar” for as long as possible before it would inevitably trigger a response from the U.S.

It is important to realize China is not acting in a vacuum. The U.S. has a clear role in how this situation evolves. The American response to China’s rise appeared to be guided by two principles. The first is that eventually China would accept U.S. hegemony and the trading system America had created after WWII. The second was that communism was fundamentally flawed and China would eventually develop into a capitalist democracy.

Weekly Geopolitical Report – Rethinking China: Part I (July 27, 2020)

by Bill O’Grady | PDF

President and General Secretary Xi Jingping has changed the course of Chinese governance. Deng Xiaoping Peng created a collective leadership model to prevent the rise of another Mao. Leaders were carefully selected and surrounded by leading figures of the various factions of the Communist Party of China (CPC). Term limits were put in place to restrict a President/General Secretary to two five-year terms. Deng established a structure of government which was somewhat decentralized. Cults of personality were discouraged.

Xi Jinping has reversed these measures. He has ended the restrictions on term limits. The Standing Committee of the Politburo is mostly composed of allies. Instead of using the structure of government that diffused power, Xi has created a series of informal committees that actually execute policy; this gives him nearly complete control of the government. “Xi Jinping thought” is now discussed in party and academic circles; although no one has bound them into a little red book, it would not be a surprise if that were to occur.

Xi is also changing China’s foreign policy. Under Deng, foreign policy was all about “hide your ambitions and disguise your claws.” Under Xi, foreign policy has been more assertive. However, over the past 18 months, we have seen aggressive and, perhaps more importantly, widespread actions. China seems to be willing to create tensions across a broad spectrum, which does appear to be a new development.

There are two broad themes to this report. In Part I, we will frame China’s situation using Japan as an analog. In Part II, we will continue the analog, discuss recent Chinese aggression and offer a detailed analysis of the potential motivations of Chinese and U.S. policymakers. As always, we will conclude the discussion with potential market ramifications.