Tag: tariffs

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – Our Take on the Initial Trump Tariffs (February 18, 2025)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

While investors broadly understood that the new Trump administration would impose import tariffs as a key part of its economic policy, concrete details weren’t available until the initial tariff announcements on February 1. Even though some of those tariffs were quickly “paused,” the announcements gave us our first chance to explore how the administration intends to wield this weapon against other countries. This report provides our first take on the initial Trump tariff policies. As we show below, we think it’s still too early to gauge the impact that trade policy will have on inflation. What we can say is that the policies are likely to be disruptive for many sectors of the global economy, potentially prompting safe-haven buying in US Treasury obligations and precious metals.

In its February 1 announcement, the administration imposed 25% tariffs on most goods from Canada and Mexico, 10% tariffs on Canadian energy imports, and additional 10% tariffs on imports from China. For legal basis, the White House cited emergency economic authority based on fentanyl trafficking from those countries. Within about 48 hours, however, the administration announced a one-month pause in the tariffs against Canada and Mexico after those countries agreed to minor concessions, such as deploying more troops to their borders with the US to clamp down on illegal crossings and drug shipments. As of this writing, Beijing has made no concessions, so the tariffs on Chinese imports remain in place. At some point, the administration is also expected to impose tariffs against the European Union and potentially against multiple individual countries in Asia and beyond.

Mainstream economists tend to believe that import tariffs are inflationary, at least in the short term, because they can restrict the supply of goods to the domestic market. However, we don’t think investors should blindly assume that’s the case. For many reasons, tariffs may not put much upward pressure on prices. After all, some importers may have little market power and be unable to pass the cost of the tariffs onto their customers. In those cases, the importer would simply suffer lower profit margins. The threat of higher input prices might also discourage firms from investing, reducing overall demand in the economy and potentially offsetting price pressures. The impact on prices would likely differ across industries, depending on how quickly each industry can adjust to the tariffs. Therefore, much depends on whether the tariffs are applied broadly against all imports or targeted against specific trade partners and/or products. Finally, retaliation by the targeted trade partner has to be considered. For instance, countries hit with US tariffs might slap tariffs against US goods, thereby slowing down export growth, increasing domestic supply, and weighing on price pressures. The targeted countries might also impose retaliatory tariffs or embargos on their exports to the US, pushing up inflation.

Nevertheless, although it’s difficult to gauge the impact of tariffs or related trade barriers, the discussion above shows they can certainly be disruptive. Even the modest additional tariffs of 10% against the Chinese, which are already in place, will likely prompt reactions from businesses and consumers, and the net impact of those reactions remains unknowable. Beijing has also already retaliated by imposing tariffs on some US goods, preparing to curb shipments of certain minerals to the US, and ratcheting up regulatory scrutiny of US firms operating in China. For now, we think the main market reaction to the tariffs relates to the potential for economic disruption and uncertainty. In particular, it appears the tariffs have prompted investors to bid up safe-haven assets such as gold, silver, and longer-term bonds.

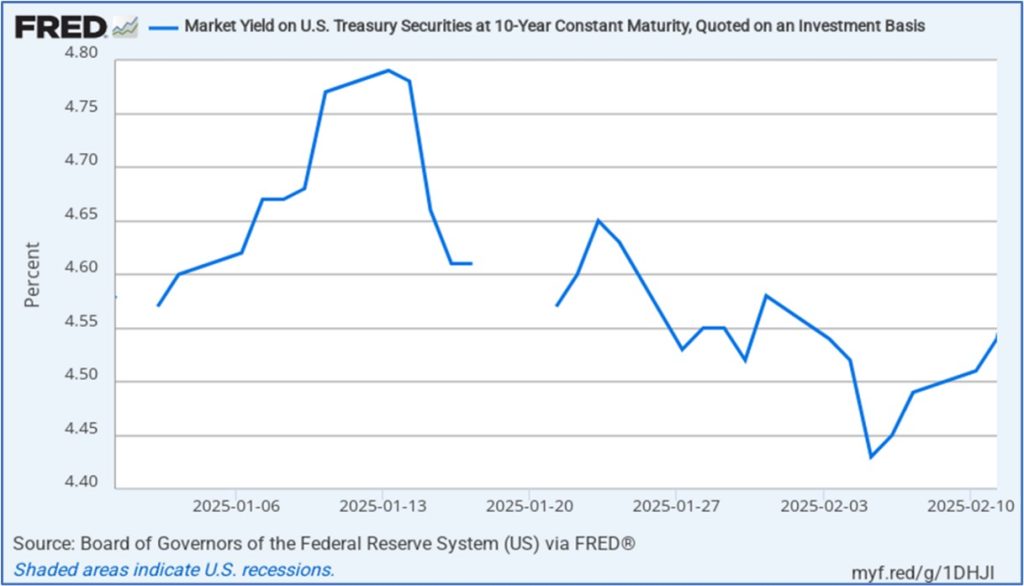

As shown in the chart below, the yield on 10-year US Treasury notes rose sharply to 4.65% over the first two days after President Trump was inaugurated, when investors were pleasantly surprised by the lack of any immediate tariff action despite the president’s earlier promises. Over the following two weeks, however, as the administration put more of its policies into place and investors could sense the possibility of economic disruptions, they bid up Treasurys, driving down yields. Once the Canadian, Mexican, and Chinese tariffs were announced at the start of February, the flight to safety intensified, pushing Treasury yields even lower to below 4.45%, although they have rebounded somewhat since then.

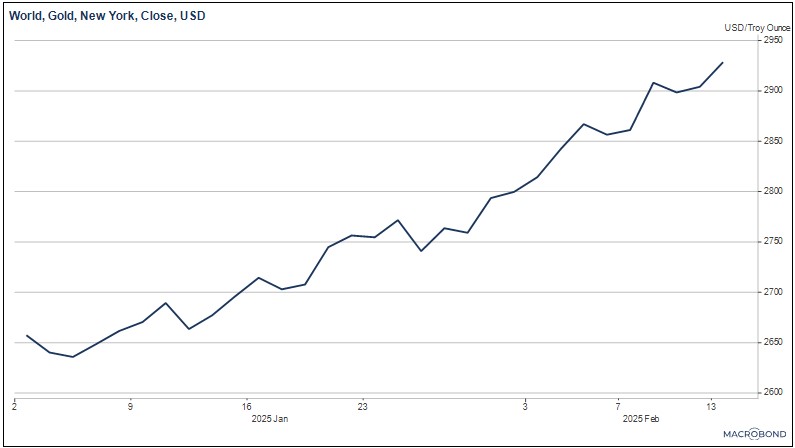

In the next chart, we show the progression of gold prices over the same period. Here, we see a pullback in gold prices in the period immediately after Trump’s inauguration, when his earliest executive orders and other policy announcements still seemed relatively tame to many investors, reducing the demand for safe-have assets. By early February, once the tariffs were announced, the general uptrend in gold prices re-accelerated, driving prices for the yellow metal to record highs above $2,900 per ounce.

As mentioned, it’s still too early to know whether Trump’s apparently neo-mercantilist economic policy and its associated tariff program will be inflationary. However, it does seem clear that investors are focused on the risk that the tariffs will drive prices higher and the potential for them to create economic disruptions. Investors are therefore bidding up traditional safe-haven assets, including longer-term Treasury obligations and gold. If and when the administration applies tariffs to the EU or other economies, we suspect longer-term Treasurys and gold could see another round of safe-haven buying. Based on technical analysis, we think the yield on the 10-year Treasury could be pushed down to its next major support level at about 4.17%, while gold could be pushed higher to its next expected resistance levels of $3,000 or $3,100 per ounce. Treasurys and gold could continue to be well bid until investors sense that the international trade environment has stabilized.

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – #129 “Let’s Talk About Tariffs!” (Posted 11/11/24)

Asset Allocation Bi-Weekly – Let’s Talk About Tariffs! (November 11, 2024)

by the Asset Allocation Committee | PDF

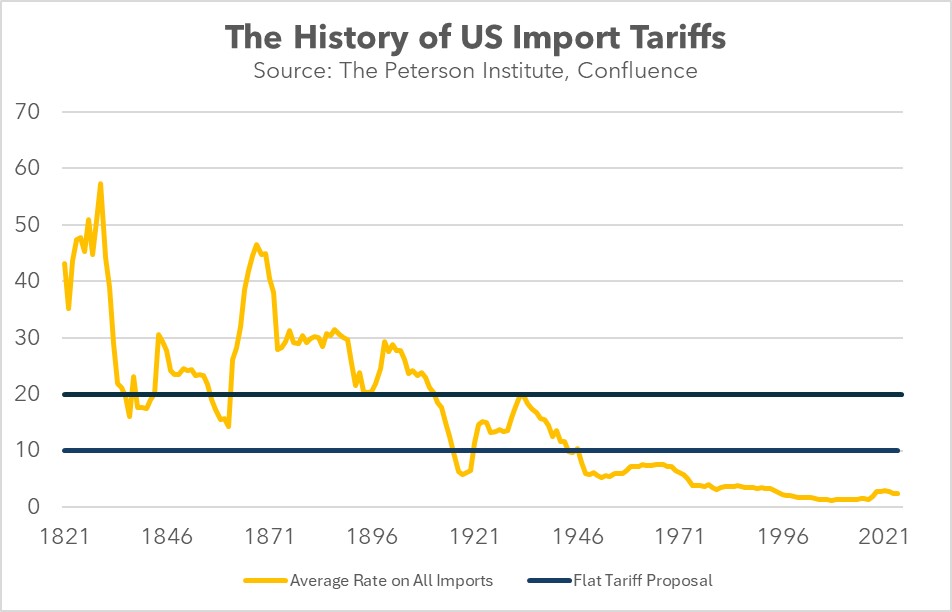

In recent years, tariffs have made a surprising comeback. Once widely condemned as a relic of the protectionist past, tariffs reemerged in 2016 as a policy tool against China and are now being considered for implementation on goods from all other countries. Populists tend to believe that these tariffs can be used to address a range of domestic economic issues, including persistent trade and fiscal deficits. They also generally believe that by leveling the playing field for domestic industries, tariffs can ultimately boost living standards for American households.

Under the new proposal, the US would impose a blanket tariff of 10% to 20% on all imports, with additional tariffs of 60% to 100% on goods from China. This would significantly increase the US’s average tariff rate to its highest level in nearly eight decades. The primary goal would be to protect US manufacturers and incentivize foreign companies to shift factory operations to the US, thereby creating domestic jobs. Furthermore, proponents believe that the increased tariff revenue could help reduce the US federal budget deficit. This proposed strategy has resonated with a substantial portion of the American electorate.

Despite its popularity with certain segments of the population, the proposal has faced significant opposition as it contradicts conventional economic wisdom. A tariff is a tax imposed on imported goods. Typically, it is levied as an ad valorem tax, which means it is calculated as a percentage of a good’s value. For instance, if the tariff rate were 10%, then importing a car valued at $10,000 would require paying a tariff of $1,000.

The potential increase in import costs has raised concerns about the proposal’s impact on price inflation. While businesses initially bear the cost of import tariffs, they can often pass a significant portion of this cost onto consumers in the form of higher prices. This economic phenomenon, known as tariff pass-through, is particularly prevalent for goods where businesses have significant pricing power. However, the extent to which tariffs can contribute to inflation and impact the overall economy varies.

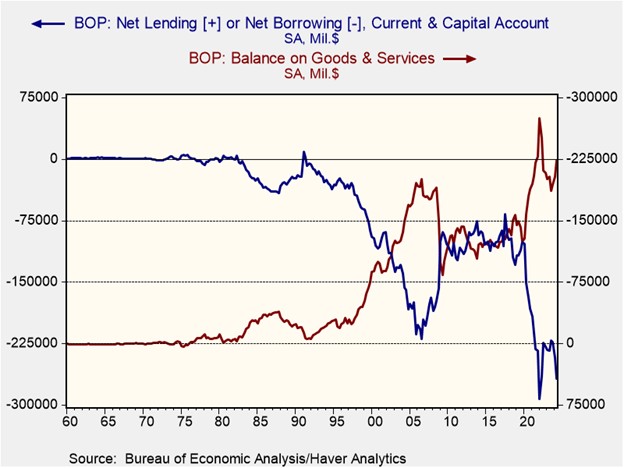

When US consumers and businesses purchase foreign goods by paying in dollars, the foreign seller typically will exchange the greenbacks received for their own currency in the foreign exchange market. Therefore, increased US demand for foreign goods should lead to increased demand for foreign currencies, which in turn could weaken the US dollar. However, foreign countries often recycle their dollar holdings back into the US economy, in which case the foreign inflow can paradoxically buoy the dollar and widen the US trade deficit, or at least limit the dollar depreciation and the narrowing of the deficit.

For a flat tariff to successfully reduce trade and fiscal deficits without exacerbating inflation, the US would need to transition from a consumption-driven economy to an export-oriented one. US consumers would need to scale back their demand for tariff-laden imports and/or US producers would need to increase their exports. This shift would require the US to reduce its reliance on borrowing and become a net lender to the global economy. By increasing exports, the US could offset the negative impacts of tariffs and strengthen its economic position. Countries, like China, have achieved this transformation by implementing policies that encourage saving and discourage consumption, often at the expense of social safety nets.

The US dollar’s dominance as the global reserve currency could hinder an export-led growth strategy. Historically, large US trade deficits have supported the dollar’s role as other countries have relied on it for international transactions. To shift this dynamic, the US might need to diminish the dollar’s appeal. This could involve implementing capital controls, as many developing countries do, in order to restrict cross-border capital flows. Alternatively, the US could sacrifice monetary policy autonomy, either by pegging the dollar to another currency or by joining a currency union with other nations.

Because we don’t expect the US to make all the necessary adjustments to become more export-oriented, we believe that potential tariffs could induce foreign countries to devalue their currencies to offset the impact of the tax levy. Accommodative monetary policy could make this possible. This scenario would benefit US companies with limited foreign revenue, such as small and mid-cap companies, as their revenues would likely remain unaffected by currency depreciation. However, this could negatively impact US exporters that rely on foreign sales as the price of their goods could become less competitive.