by Thomas Wash | PDF

Six months into his presidency, Reagan backed restrictive monetary policy to combat inflation. While the move initially drew criticism for its short-term economic pain, many viewed it as a necessary step toward long-term stability and growth. This optimism was ultimately vindicated, paving the way for Reagan’s landslide reelection in 1984. The lesson: an early-term recession, though difficult, can create strategic opportunities to push a bold and transformative agenda forward.

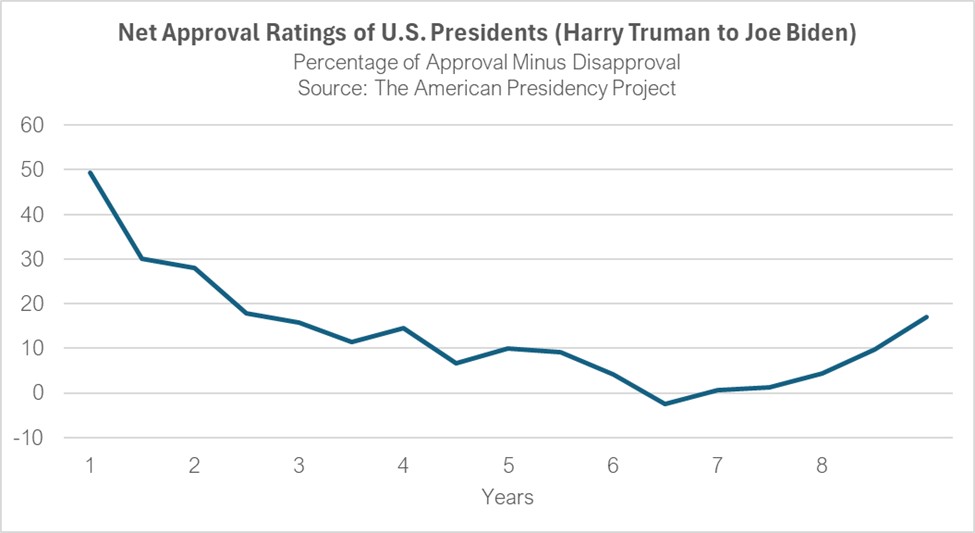

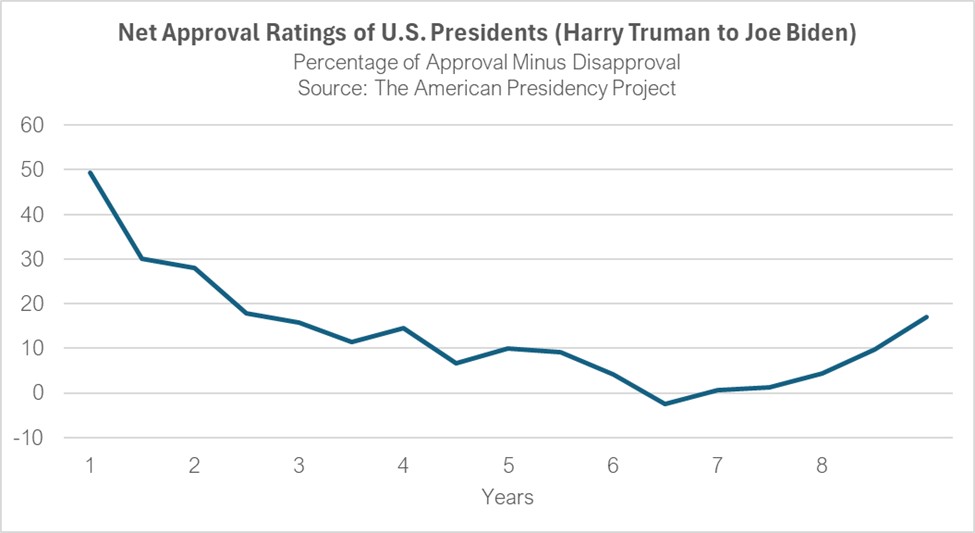

A president typically wields the greatest amount of political capital at the outset of their tenure. This period, often referred to as the “honeymoon phase,” is usually marked by peak public approval, fueled by the optimism and goodwill that was generated during the election campaign (see chart below). Supporters are often energized, and even those who may not have voted for the president often extend a measure of deference and give the new administration an opportunity to set the tone and pursue its agenda.

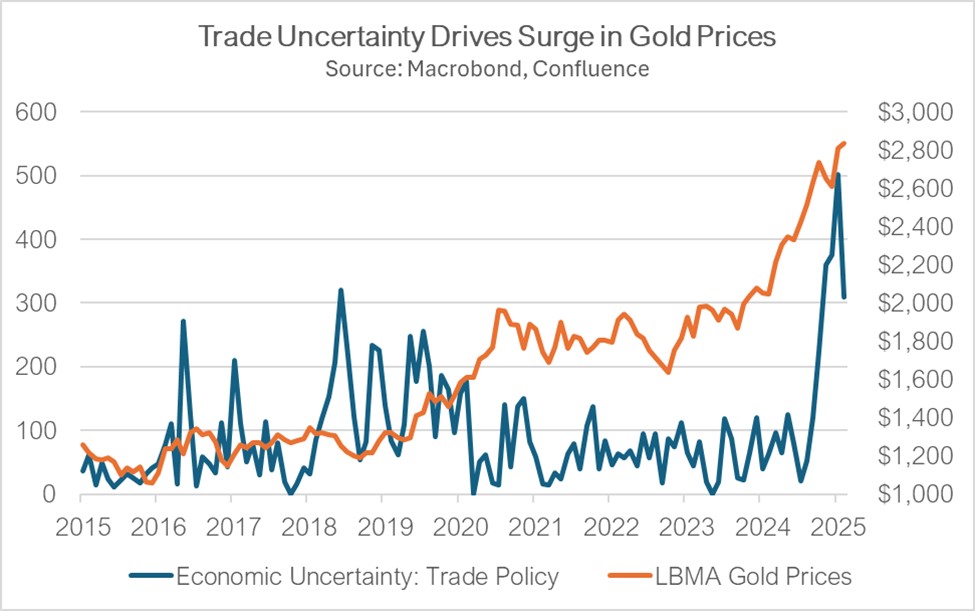

During this pivotal period, President Trump has escalated his aggressive trade war with the rest of the world. It appears that the administration’s strategy is to weather any associated short-term economic challenges — such as heightened market volatility caused by unpredictable trade policies and budget cuts designed to strengthen the government’s fiscal position — in order to achieve a broader goal of transforming the US economy from one driven by high consumption to one that prioritizes export promotion.

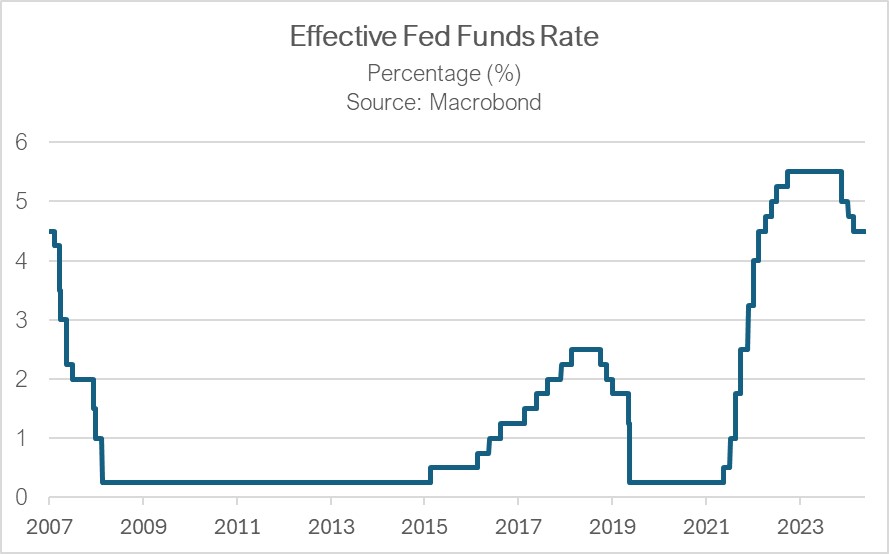

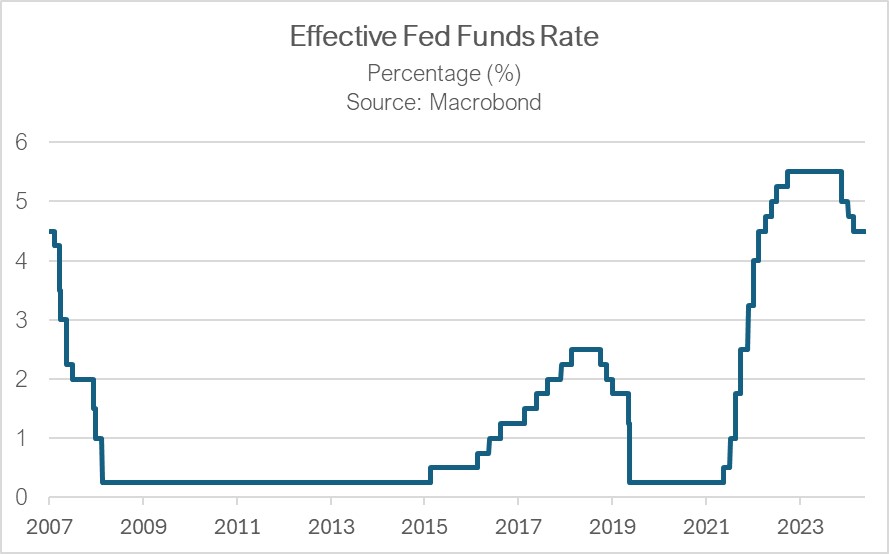

The administration’s ability to manage an economic downturn will be largely influenced by the capacity to lower long-term rates, especially in today’s high interest rate environment, as well as the fiscal flexibility created by recent efforts to curb government spending. Extending the 2017 corporate tax cuts could also provide businesses with a financial buffer, enabling them to adapt to the impact of new tariffs.

Importantly, the Trump administration is apparently counting on the Federal Reserve to serve as an economic safety net in the event of a severe downturn. While the central bank has already reduced rates by 100 basis points from their peak during the tightening cycle, it still has the ability to cut rates and restart balance sheet expansion, if needed. These measures could enable households to refinance their mortgages at lower rates, thereby improving household balance sheets and paving the way for higher spending.

That said, this strategy carries significant risks. For example, if the downturn persists for too long, it could potentially trigger a financial crisis, undermining household confidence and consumers’ willingness to spend. In such a scenario, the government might be forced to take more drastic measures, such as implementing a bailout or fiscal stimulus to restore confidence and stabilize the economy. Such spending could lead to a sharp increase in government debt, raising concerns about its long-term sustainability and potentially leading to a period of stagnating growth.

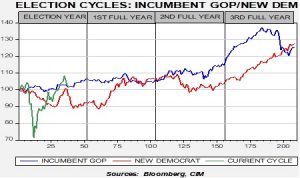

While there is no reward without risk, the president’s ability to slow the economy to implement longer-term, sustainable reforms also hinges on his capacity to embrace short-term political pain in exchange for long-term gain. For example, we note that while the Reagan recession was relatively short, it resulted in Republicans losing House seats to the Democrats. This scenario could present considerable challenges for the Trump administration. Unlike President Reagan, who successfully advanced his agenda by working across the aisle, Trump may find himself constrained by a lack of bipartisan cooperation given the current political climate. As a result, he may be more incentivized to ensure that Republicans regain and possibly add to their majority in Congress, something Reagan was not able to do in the mid-term elections during his first term.

In such a scenario, the president would need to pivot strategically, prioritizing the delivery of a tangible and widely recognized victory to the public ahead of next year’s primary election to sustain momentum and galvanize support. This could take the form of highlighting major achievements, such as breakthroughs in trade negotiations or the successful passage of the long-awaited tax bill.

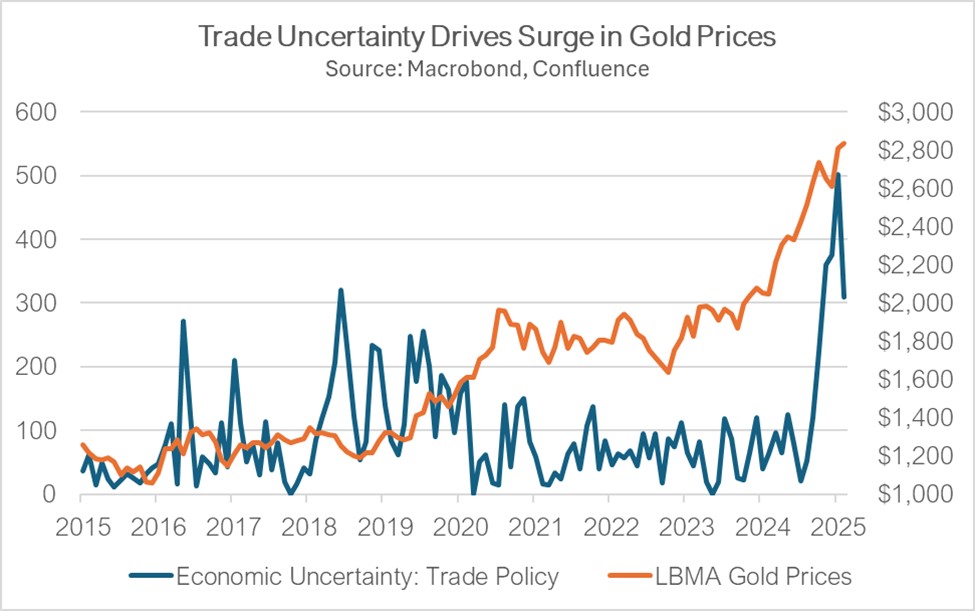

We continue to believe that equities will be able to produce attractive long-term investment returns, especially if the Trump administration achieves its long-term goals. However, given the current level of uncertainty and the risk of near-term economic disruptions, we also see gold as an attractive option. Additionally, the potential for a decline in long-term interest rates could make this an opportune time to extend duration in government fixed-income securities.

View PDF